A high point of director David Lean’s illustrious film career was the epic war film The Bridge on the River Kwai. Before producing this film, Lean was turning Charles Dickens novels into cinema and exploring such themes as class disparities as individuals charted his or her life’s course. Later as Lean went on to receive Academy Awards for such films as Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, and A Passage to India, he would address his preferred issues against the backdrop of an increasingly globalized 20th century and the cultural clashes between East and West.

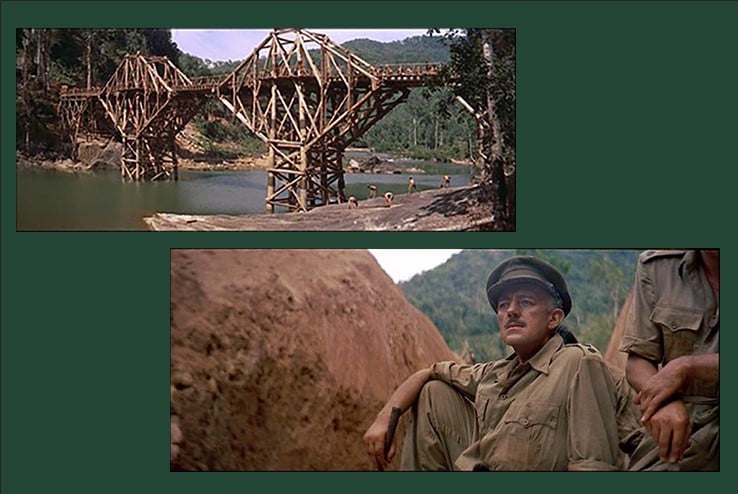

In Bridge on the River Kwai, we find a fictional account of the building of a bridge that was to be part of the Burma Railway. The movie is set in Thailand during World War II, and the two commanders in this drama, the honor-bound Japanese Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) and the duty-bound British commander, Nicholson (Alec Guinness) represent in a sense the East-West cultural divide. Both are victims of their circumstances, as military men who must carry out orders. Saito, however, has the upper hand as the British are his prisoners of war. He shows disdain for his British prisoners, proclaiming in one telling moment his utter contempt for them: “I hate the British! You are defeated but you have no shame. You are stubborn but you have no pride. You endure but you have no courage.”

The tension between the two commanders is clear from the outset. Saito needs Nicholson’s men to build his bridge by a certain date. Nicholson is adamantly opposed and cites the Geneva Convention which prohibits the use of war prisoners as slave labor. When Saito resorts to cruel tactics to coerce the British army to comply, Nicholson demonstrates courage and resolve. He defies Saito’s orders and commands his men to do the same. Saito, seeking to make an example of Nicholson, has his men beat the British commander, and toss him into “the oven” which is a locked box subject to intense heat. He also deprives the British commander of food and water.

When Nicholson finally emerges from the oven, he takes a different position. He allows himself to be talked into having his men build a beautifully engineered British bridge. Although this project will serve Japanese interests, to the detriment of the British and Allied forces, Nicholson becomes convinced that the work will reinvigorate his disheartened troops.

Two characters in the film provide a counterpoint to the mindset of Saito and Nicholson. William Holden’s character Shears, an American who is placed in the POW camp but quickly escapes, exemplifies an individualistic perspective, in contrast to the group solidarity espoused by Nicholson. Shears doubts the British soldiers will survive under Saito’s harsh rule and prioritizes individual life over military rules. Nonetheless, Shears also dissuades members of Nicholson’s army from deserting, urging them to listen to their commander.

Coincidentally, Shears is believed to be dead through much of the film but emerges toward the end, playing an active role in the commando mission that leads to the destruction of the bridge. The second character, and the film’s embodiment of British wartime patriotism, is the British military doctor, Major Clipton (James Donald). He is the sole character who refuses to cooperate with either Saito or Nicholson’s bridge project. He shows conviction and courage, advocating for Nicholson in the beginning when no one else did. He also won’t sacrifice the men’s health in order to build the bridge, which puts him at odds with the Colonel; nor will he take part in a ceremony on the bridge to celebrate its completion, because he viewed it as aiding the enemy. His loyalties are intact. It’s not surprising that Clipton utters the film’s famous last lines as it reaches its tragic end, “Madness, madness, madness.”

Lean, to his credit, provides a sensitive, thoughtful depiction of what were then still raw historical events. One must remember that in the 1950s the war with Japan and the building of the Burma Railway were fresh memories. Significantly, the screenwriters, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were both blacklisted in Hollywood for their far-left associations, and so the script was written in secret, without divulging their names. When the screenplay won its well-earned Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, the credit went to Pierre Boulle, the French author of the 1952 novel by the same name. Credit was given to Foreman and Wilson, albeit posthumously.

In the final minutes of the film, Guinness as Colonel Nicholson, stumbles around, a dead man walking. He is aware of his actions and suddenly horrified by what he had perpetrated as a British officer. You see the terror in his eyes as he looks back at the engineering masterpiece that he’s built for the enemy and asks, “What have I done?” It’s a rhetorical question of course. In Lean’s world, Nicholson should not be viewed as evil. Circumstances compel men to act in ways that they later regret.

This nearly 70-year-old war film was in some sense an anti-war film. It presents its military characters as non-heroes, indeed, as regular men who are trying to conduct themselves with dignity in trying times.

Leave a Reply