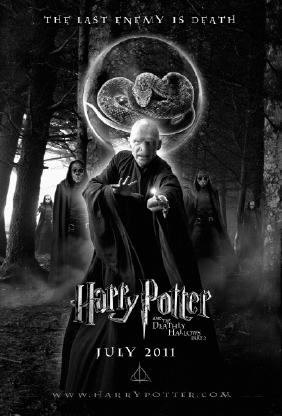

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2

Produced and distributed by Warner Brothers Pictures

Directed by David Yates

Screenplay by Steve Kloves, from J.K. Rowling’s novel

I took my son Liam to the first Harry Potter movie ten years ago, so I thought it only proper to let him take me to the last chapter in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, yesterday.

Even now that he’s a young man, Liam still thinks the world of Harry Potter. For him, it’s now a matter of nostalgia, I suspect. It all began when he started reading J.K. Rowling’s stories of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry as a fourth grader. His dedication to the series is matched only by his enthusiasm for Arthur Conan Doyle and C.S. Lewis.

I confess that, during his younger years, Liam’s interest in Rowling and her broom-riding heroes and heroines troubled me. After all, wizards, witches, and their spells had been driven underground centuries ago in order to relieve good men of the unpleasant necessity of roasting such malefactors at the stake. The task had come to be regarded as thoroughly upsetting, what with the screaming and smell of charred flesh.

Liam has insisted through the years that I had it all wrong and that Rowling’s purpose was essentially moral. Furthermore, he’s fond of pointing out, the later installments of the series are replete with Christian images and themes. I had been doubtful of these claims, but this final film seems to prove him right. Which is not the same thing as saying I found the movie or its predecessors terribly entertaining. Somehow, the enchantment Harry Potter casts on his fans continues to elude me. I guess I’m naturally wand resistant.

As proof of my continuing resistance to Potter charm, 20 minutes into the showing we attended, I was struggling to stay awake, as Harry and his friends whizzed here and there in search of a Horcrux, which, as everyone knows, is an object invested with a piece of the dark wizard Voldemort’s soul. Feeling I was letting my side down, I slipped out to the concession to fortify myself with a $3.50 paper cup of Starbucks coffee (I felt I couldn’t afford a cappuccino at $6.50) and a $7 medium-sized bag of popcorn. (The jumbo at $12 was entirely out of my reach.) Back in my seat, I sipped the black coffee as Liam ate the popcorn and explained sotto voce that Harry had located the Horcrux and was trying to destroy its evil content and thus bring Voldemort that much closer to defeat. I dutifully scanned the screen for confirmation of this, but my attention strayed to something else. I noticed that the audience was unnaturally silent. To my left a couple seemingly in their 40’s was gaping rapturously at the proceedings. The adolescents in the row beneath us were all on the edge their seats, silently gripping the railing before them. No one was talking. What’s more, there was no coughing, no thrumming cell phones, no rattling cellophane. I hadn’t been with an audience this quiet since watching the last act of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.

These people were under a spell. Not a magic spell—it was something far stronger. They were witnessing a story of a villain whose mad quest for immortality had brought him athwart an unexpectedly formidable obstacle: a young man precociously resigned to his own mortality and thereby equipped with genuine moral strength. The film was unfolding an old and now somewhat unfashionable story. Nevertheless, in this telling director David Yates, following Rowling closely, had found means to compel the silent contemplation of the audience around us. The moviegoers evidently recognized in the yarn something that they needed.

Rather than say more, at this point I’m going to turn matters over to Liam. He knows the series far better than I do. Here’s what he has to tell us.

When it was published in 1998, the American edition of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone provoked the ire of many parents and religious thinkers who thought they detected occult and satanic undertones in its story. In some locations, it was banned from bookstores and libraries and taken from children who had already obtained copies. A couple of years before his elevation as pope, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, writing in a private letter, suggested the novel might “deeply distort Christianity in the soul before it can grow properly.” So it is at once ironic and heartening that the series, both the novels and the films, should end with an allegory of the Christ story. Actually, this is not as surprising as it may seem at first. J.K. Rowling has commented along the way that writing her Potter stories has been her way of coming to terms with her own Christian faith.

This, I think, will be apparent to those most familiar with the series. For those who haven’t followed the novels and their adaptations, however, Deathly Hallows: Part 2 may prove a challenge. It’s a film that has the luxury of being almost entirely paced in climax mode. Having handled narrative exposition in Part 1, director David Yates and his team of cinematic wizards pick up from the final moments of the previous film and, after a few quiet conversations among the film’s principals, throw the narrative into top gear and hardly let up until reaching the epilogue.

Yates wastes no time getting Harry back to Hogwarts. Reunited with old classmates and fellow Voldemort opponents, Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) goes to work to save the world once and for all. He and his friends, Hermione (Emma Watson) and Ron (Rupert Grint), must hunt down the remaining Horcruxes (material objects hiding slivers of dark souls) and destroy them in order to make Lord Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes) mortal and therefore vulnerable once more.

In defense of Hogwarts Castle, magical shields arise, untenanted suits of armor come to life, and giants lumber through the fray. As the battle rages, the beloved school begins to crumble bit by bit. The special effects are truly wondrous; they never seem like special effects at all. The battle that destroys Hogwarts features a good deal of computer-generated imagery, but Yates never allows the engineered spectacle to overshadow the characters. The last hour or so is full of character development and story-line resolutions. Fan favorites such as Neville Longbottom (Matthew Lewis) get their time in the spotlight, and romantic couples are united at last. Particularly poignant is the revelation concerning Harry’s professor, the seemingly malevolent Severus Snape. The film treasures these moments and appropriately gives them priority over the simple shock and awe of magical warfare. These passages—some tragic, some triumphant—invest the unfolding events with weight and catharsis. Yates does full justice to Rowling’s conception of her characters. They seem as real on the screen as they do on the page.

The war against evil is not without loss. There are many deaths, but they’re never treated merely as a means to heighten drama. When a character dies, his or her end is portrayed with respect and due dignity. During a respite in the battle, the pace slows down, and the film adopts a mournfully contemplative mood. As Harry surveys the terrible losses and hears his friends wailing over the dead, you cannot help but feel his profound sadness. In these scenes, Harry begins to find the courage to confront his fate.

The final section of the film will surely resonate with audiences everywhere, as it deals with the complex emotions so common to our experience of death. Radcliffe, who has grown into a fine young actor, conveys this powerfully.

Ultimately, Rowling has put forth a hero who is forced to face his own mortality and finds he is able to do so courageously because of the love he has known throughout his life. Yates’ film treats this part of the story with a delicacy and tenderness generally absent in conventional action films. His movie champions not bravado but true bravery. It exalts forgiveness and, above all, love. Yes, The Deathly Hallows brings to a conclusion the most lucrative film franchise in history, but unlike so many other hugely profitable ventures, it does so honorably.

Leave a Reply