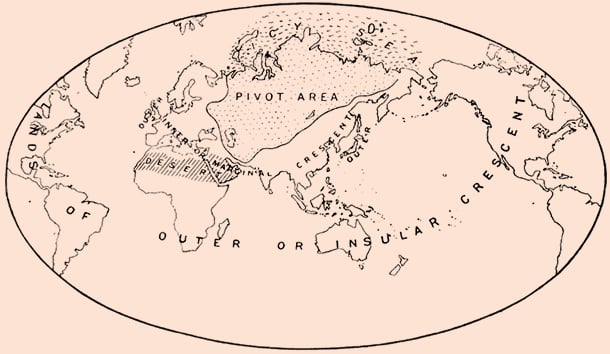

In April 1904, Scottish geographer Halford Mackinder gave a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society. His paper, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” caused a sensation and marked the birth of geopolitics as an autonomous discipline. According to Mackinder, control over the Eurasian “World-Island” is the key to global hegemony. At its core is the “pivot area,” the Heartland, which extends from the Volga to the Yangtze and from the Himalayas to the Arctic. “My concern is with the general physical control, rather than the causes of universal history,” Mackinder declared.

At the end of the Great War, profoundly concerned with what he saw as the need for an effective barrier of nations between Germany and Russia, Mackinder summarized his theory as follows:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

Who rules the World-Island controls the world.

This dictum helps explain the essence of the Ukrainian crisis, as well as the motivation behind the continuing ambition of some U.S. policymakers to expand NATO eastward.

The model has undergone several modifications since Mackinder. In his 1942 book America’s Strategy in World Politics, Nicholas Spykman sought to “develop a grand strategy for both war and peace based on the implications of its geographic location in the world.” In the 19th century, he wrote, Russian pressure from the “heartland” was countered by British naval power in the “great game,” and it was America’s destiny to take over that role once World War II was over. Six months before the Battle of Stalingrad Spykman wrote that a “Russian state from the Urals to the North Sea can be no great improvement over a German state from the North Sea to the Urals.” For Spykman the key region of world politics was the coastal region bordering the “Heartland,” which he called the “rimland.” He changed Mackinder’s formula accordingly: “Who controls the rimland rules Eurasia; who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.”

Spykman died in 1943, but his ideas were reflected four years later in Harry Truman’s strategy of containment. Holding on to the rimland, from Norway across Central Europe to Greece and Turkey, was the mainstay of America’s Cold War strategy and the rationale behind the creation of NATO in 1949. Containment swiftly turned into a massive rollback, however, when the Soviet Union disintegrated. In 1996 Bill Clinton violated the commitment against NATO expansion made by his predecessor, and the alliance reached Russia’s czarist borders. In 2004 it expanded almost to the suburbs of St. Petersburg with the inclusion of the three Baltic republics. All along Ukraine had remained the glittering prize, however, the key to limiting Russia’s access to the Black Sea, and a potential geostrategic knife in southern Russia’s soft underbelly.

The resulting, U.S.-led Drang nach Osten is a grand-strategic mistake. From the point of view of the liberal globalist-neoconservative duopoly, however, there is no better way to ensure U.S. dominance along the European rimland in perpetuity than subverting the Russo-German rapprochement with a new version of the anaconda strategy. The duopoly’s obsessions have resulted in policies that resonate with Russia’s former clients in Tallinn and Lvov, but they are detrimental to the security of the United States. Further NATO enlargement has ensured that Russian missiles remain targeted on American cities—which may be of no consequence to the denizens of Riga or Bucharest, but should focus minds in New York, Seattle, and Omaha.

Playing geopolitical games in Ukraine undoubtedly pleases some Eastern Europeans who have their own axes to grind, but it jeopardizes the prospects for long-term peace in Eastern Europe. The United States should understand why, say, the people in western Ukraine have a vested interest, and an even more acute psychological need, to treat Russia as the enemy; but America should never allow herself to be seduced by their obsessions. Various Eastern Europeans proclaim their devotion to various postmodern ideological assumptions (when they are not marching under the red-and-black SS Galizien banners, that is), but their real agenda is twofold: to have a Western—i.e., American—security guarantee against Russia, and to strengthen their own position vis-à-vis political opponents at home and against those neighbors with whom they have an ongoing or potential dispute (e.g., Ukraine and Moldova over the future of Transnistria).

The United States should not extend her protective cover, right in Russia’s backyard, to new clients whose fortunes are not vital to this country’s interests. It would be insane for the United States to assume responsibility for incompatible claims over a host of disputed frontiers that were drawn arbitrarily by communists—in the fashion of Khrushchev’s transfer of the Crimea to Ukraine in 1954—and bear little relation to ethnicity or history. At no obvious benefit to the United States, we would be asked to underwrite a post-Soviet outcome that is not inherently stable or just, let alone “democratic.”

Nowhere is this more true than in Ukraine. Western politicians and journalists refer to “the people of Ukraine,” but there is no unified Ukrainian nation. The linguistic divide between the mostly Ukrainian-speaking western and central regions and the predominantly Russian-speaking southern and eastern regions also reflects a fundamental cultural and emotional division, not merely a difference of opinion on the issue of the E.U. association agreement or the presence of the Russian Black Sea fleet in the Crimean Peninsula. It is a division between two fundamentally incompatible identities. As such, it is comparable to the divide apparent in the electoral map of the 1860 U.S. presidential election.

The Orange Revolution in the fall of 2004 produced an inept leader, Viktor Yushchenko, and a corrupt operator, Yulia Tymoshenko, whose incompetence paved the way for Viktor Yanukovych’s victory in January 2010. He also proved to be incompetent and corrupt, but in the end he was a legal president. Western powers stage-managed, aided, and abetted the violent overthrow of a democratically elected chief of state in February. They will now reap the rewards: a bankrupt economy in immediate need of some tens of billions of ready liquidity, a disintegrating country with secessionist regions that can hardly be controlled short of a civil war, and a new Cold War-like flashpoint that nobody needs.

Ukraine is an evenly divided country, by territory and by population. The “unionists” (nationalists in the west) cannot hope to subjugate and “reconstruct” the Russians and pro-Russian Ukrainians who dominate the Black Sea coast and the industrial east. The nationalists will never cajole their counterparts in the east and the south to accept an image of Ukraine defined by a visceral hatred of Russia and all her works. The nationalists’ attitude was best illustrated by the hasty repeal, two days after the putsch in Kiev, of the law allowing the country’s regions to make Russian a second official language in areas where it is extensively spoken. On the other hand, the potential “separatists” (from Kharkhov in the northeast to Odessa in the southwest) will never become Ukrainians in the tradition of Stepan Bandera and the SS Division “Galizien,” and they can never convert the western Ukrainians to the paradigm of a Moscow-friendly “borderland” (the literal meaning of Ukraine), whose destiny lies in a close association with Russia. Any great power that attempts to control the whole of this deeply divided country will come to grief.

Equating “the people of Ukraine” with the helmeted nationalists at Maidan would be a major mistake. Their nationalism is itself a hybrid phenomenon that only matured in the Polish-ruled Volhynia and Galicia between the two world wars. Its cradle is in Lvov, a predominantly Polish city until September 1939, whose ethnic composition (and that of the surrounding countryside) was irreversibly changed by the genocidal Banderists during the war and by Stalin’s commissars thereafter. Ukraine’s eastern border, on the other hand, was arbitrarily drawn in 1922 by the (mostly non-Russian) Bolsheviks, many of them hell-bent on reducing Russia in size. It includes large areas and population centers that have no historic or cultural connection to Ukraine. Last but not least, the Crimean Peninsula was transferred to Ukraine from Russia by a stroke of Nikita Khrushchev’s drunken pen in February 1954. There is nothing sacred and nothing permanent about these absurd borders. Any attempt to uphold them with the force of arms will lead to bloodshed, as Tito’s equally arbitrarily drawn internal boundaries did in ex-Yugoslavia two decades ago.

Ukraine’s disintegration can be averted only by constitutional changes that would lead to some form of devolution and the establishment of a federal state. A new political and legal framework is needed, one which would take account of the divergent interests of the peoples of Ukraine. Any attempt by the mobocracy that has grabbed power in Kiev to establish its writ in Crimea or in other southern regions, such as Odessa and Nikolayev, and in the eastern provinces, in Dnepropetrovsk, Donetsk, and Kharkov, could lead to an outright civil war.

A sane U.S. relationship with Moscow demands acceptance that Russia has legitimate interests in her “near abroad.” Ukraine’s geographic position as the transit route from the oil and gas fields of Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia to Central and Western Europe is a valuable asset. But being a transit route for a strategic commodity is not tantamount to having the commodity itself—especially when alternative transit routes, such as the South Stream, are becoming available. The proponents of a hard Western line with Moscow appear to have learned nothing from Russia’s response to Mikheil Saakashvili’s attack on South Ossetia in the summer of 2008, when Moscow maneuvered Washington into a position of weakness unseen since the final days of the Carter presidency.

For the leading powers of the European Union, the status of Ukraine is a peripheral issue unless it is seen strictly through the prism of a geopolitical zero-sum game. For the United States it has always been, and still is, an optional crisis. For Russia, however, and for her supporters in eastern and southern Ukraine, the future of the Black Sea coast and of the eastern industrial basin is an existential issue.

Leave a Reply