Chronicles Editor Paul Gottfried has devoted considerable scholarly attention to clarifying hot-button political concepts according to their original meaning and historical context. In his 2016 study, Fascism: The Career of a Concept, he explains what fascism actually once meant, in sharp contrast to the partisan reinvention of this term in our own age. In his new book, Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade (2021), he similarly shows how traditional antifascism bears almost zero resemblance to its meaning in today’s media and political circles.

Why are these scholarly endeavors necessary? As Gottfried explains in Antifascism, people who lived between the 1920s and World War II had a specific phenomenon in mind when they referred to fascism. These people knew what Nazism was. “Perhaps most importantly, fascists or Nazis identified themselves as such,” Gottfried wrote. “This is not the process of identification that is currently taking place.”

Nowadays, fascism has been identified with disparate causes such as immigration restriction, border controls, opposition to transgenderism, and regulation of international trade for the benefit of the working classes in liberal democratic states.

Although Gottfried’s focus is on the abuse of the “F-word” in America and Europe, his study is very relevant to Canada as well. The Canadian right and the left are equally guilty of slinging this term at their opponents. On the left, the Canadian journalist and The Nation correspondent Jeet Heer has eloquently attacked as “some serious fascist shit” the apparent preference of the Bloc Québécois (a party that seeks the separation of Quebec from Canada) for purelaine Quebeckers who have a French-Canadian ancestry. On the right, Maxime Bernier, the leader of the People’s Party, has called Prime Minister Justin Trudeau a “fascist psychopath” for criticizing opponents of COVID vaccinations.

In 2021, the online version of the radical leftist magazine Monthly Review published an article titled “Canada supports fascism,” which accuses Trudeau’s government of lending support to “fascist” movements in Hong Kong, Israel, and the Ukraine. Yves Engler, the author, darkly warns that “it’s almost a principle of Canadian foreign policy to support fascistic, far right, groups.”

Not to be outdone, Trudeau, around the same time, offered these reflections at an international conference on anti-Semitism and racism:

We see the organizations of extremist groups on the far-right and the far-left that are pushing white supremacy, intolerance, radicalization, promoting hatred, fear and mistrust across borders but within borders, as well.

Since Trudeau failed to explain what he meant by “white supremacy” or how extremists on both the left and the right contribute to it, his remarks were just as unclear as those of critics on the left and on the right who have accused his government of harboring fascist sympathies. In February of this year, Trudeau added to this confusion by dismissing a mass convoy of truckers protesting vaccine mandates in Ottawa (the nation’s capital) as just “a few people shouting and waving swastikas.” They don’t define who Canadians are, he said. (Presumably, only he enjoys that privilege.)

Judging from these statements, one might think that Canada, once celebrated as the “peaceable kingdom,” not only has a long history of kowtowing to right-wing extremism but also continues this tradition to the present day. But what exactly is fascism? As Gottfried constantly reminds his readers, only a careful study of history can answer this question.

The misuse or misunderstanding of fascism in Canada is often evident even in sophisticated academic circles. In 2006, Max and Monique Nemni published the first volume of a comprehensive biography of one of Canada’s most controversial prime ministers (and Justin’s father), Pierre Elliott Trudeau. This volume, titled Young Trudeau: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada, 1919-1944, is a well-written and meticulously documented portrayal of its subject’s youthful journey through the world of conservative Catholic Quebec in the 1930s and 1940s. The reader is treated to a very engaging narrative authored by two scholars who have taught in Quebec’s university system.

Yet the Nemnis, who are married to each other, also portray old Quebec as a dark and prejudiced place dominated by fascist sympathies. More specifically, they are determined to show that the young, impressionable Trudeau enthusiastically shared these sympathies, which academics, journalists, and the clergy actively encouraged in La belle province at this time.

(Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 3.0)

As friends of Trudeau, the Nemnis were stunned by these discoveries, based on their study of his private papers and diaries that had never been released to anyone until his biographers requested access to them. The authors’ surprise is understandable since, as prime minister during the late ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, Trudeau promoted multicultural immigration from the Third World, official bilingualism in the civil service, the grievances of disaffected minorities, and a foreign policy friendly to Communist dictators, such as Fidel Castro. None of this sounds even remotely fascist. Trudeau also carefully projected an image of rebelling against authority or rowing “against the current” all his life.

The Nemnis, however, discovered that Trudeau enthusiastically conformed to dangerous ideas that were prevalent in his youth. “Always in harmony with the people around him, he rose to the defence of an ethnic and organic nationalism.” Yet this harmony represents to the authors a dark embrace of fascist ideas and themes.

If the Nemnis are correct, young Trudeau encountered this ideology as a central element of his education in old Quebec. Born in Montreal and raised in a privileged background made possible by his wealthy father, young Trudeau was able to attend the finest Catholic schools that Quebec had to offer. Although this schooling provided rigorous instruction in the learning of languages, philosophy, politics, and debating, it also exposed him to the anti-English and anti-liberal sentiments that dominated Quebec’s politics at the time.

The shocking devastation of the Great Depression, as the Nemnis explain, persuaded many of the clergy “that the root causes of the crying social problems [in Quebec] were planted in Protestant Anglo-Saxon individualism and materialism.” Moreover, these ideas “led to the ‘excesses of capitalism’ and to the liberal democratic mentality.” These “imports,” in other words, were alien to the true French Catholic ethos in Quebec. Given the fact that fascist movements in Europe also opposed these ideas, it is tempting to agree with the Nemnis that fascism was alive and well in Quebec at the same time.

But none of these attitudes was inherently fascist. In fact, prominent conservatives in the distant past held similar views. However, the Nemnis are determined to persuade their readers that this popular antipathy to Anglo-American capitalist liberalism went hand in hand with key fascist ideas.

One of these ideas was corporatism, an ideology that is historically associated with Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy. In basic terms, corporatism involves the organization of society according to different economic interests, whose prime duty is to serve the “common good.” In the dark years of the Great Depression, corporatism offered an attractive alternative to both capitalism and socialism. It was particularly appealing to French-Canadian Catholics who hated English capital’s dominance over Quebec’s economy as much as they detested atheistic Bolshevism.

One of the oldest Catholic Churches in North America, Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Catholic Church in Place-Royale in Old Quebec, Canada (Wilfredo Rodríguez / Wikimedia, public domain)

Many Catholics enthusiastically supported Pope Pius XI’s 1931 encyclical on social justice, Quadragesimo Anno. In this document, which appeared on the 40th anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum, Pius XI warned that liberalism is “the father of this Socialism that is pervading morality and culture and that Bolshevism is its heir.” In the encyclical, the Pope endorsed corporatism as the only program available to Catholics. Pius XI was also a fierce critic of Mussolini’s later drift towards anti-Semitism and famously declared in 1938, “Spiritually we are all Semites.”

Inspired by Quadragesimo Anno, the Archbishop of Quebec, Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Villeneuve, urged the laity in 1933 to support “an economico-social program that conforms to Catholic principles.” In the same year, the Jesuit Louis Chagnon composed an article entitled “Catholic Social Guidelines,” which was also based on the 1931 encyclical. One of these guidelines called for the replacement of a “spirit of dominating and greedy egotism” with the “true Christian spirit.” Apparently, there was no opposition between Christianity and corporatism, given the fact that another guideline called for the “establishing of a corporatist order through the complete and legal organization of the different occupations or industries.”

In Quebec, a new social contract that celebrates bureaucratic statism and sexual permissiveness has replaced Catholic traditionalism.

It is no accident, as his biographers argue, that Trudeau’s and others’ embrace of corporatism coincided with a robust admiration of right-wing regimes that actually practiced it. But according to the Nemnis, corporatism was practically fascism:

None but the fascist regimes had adopted the corporatist model; not a single democracy had done so. That was not mere coincidence. A glance at the role and the power of the state in corporatist regimes is revealing.

Moreover, the Nemnis believe this pro-corporatist feeling demonstrates that “the majority of the members of the French-Canadian elite was not only opposed to conscription, but also sympathetic to fascism.” In short, the Nemnis interpret Quebec’s opposition to conscription during World War II as barely concealing much more sinister political inclinations.

As a law student at the Université de Montréal in the early 1940s, Trudeau co-wrote a manifesto calling for a “révolution nationale” that would create a “sovereign French Canadian state” by coup d’état. This new regime would be based on corporatist principles. His biographers interpret this embrace of corporatism as practically identical to support for the regimes of Salazar, Mussolini, and Marshal Pétain’s France. “It was to these three models of ‘successful’ corporatism, especially that of Pétain, that Trudeau turned as he prepared to start his own revolution,” the Nemni’s write.

Were admirers of corporatism, however, necessarily fascists as well? What Chagnon proposed for Quebec sounded like the aims of FDR’s New Deal. As Terence J. Fay explains in A History of Canadian Catholics: Gallicanism, Romanism, and Canadianism (2002), Chagnon’s 13-point program called for a corporatist state in which important groups such as farmers, labor, artisans, big business, and civil servants would oversee the economy for the common good. In policy terms, the state would provide medicare, protection for the elderly, safer working conditions for the laboring classes, and a living wage for workers with families.

Contrary to the impression given by the Nemnis’ account of history, Mussolini’s corporatist policies persuaded many observers that he was a man of the left, at least prior to his fateful alliance with Nazi Germany. Some of Il Duce’s early fans included FDR’s brain truster Rexford Tugwell and the left-leaning editors of The New Republic. As Gottfried explains in Antifascism, “Fascism may, in fact, have looked sufficiently leftist to make it appealing to social reformers outside of Italy.”

Nevertheless, it is hard to find any cleric in Quebec at this time endorsing the fascist portrait of human nature, which celebrates the unleashing of raw will and instinct that would violently stamp out any attempt to encourage an altruistic moral sensibility. The tendency of Latin fascism to embrace Roman neo-paganism and the cult of the warrior was utterly absent among Quebec’s Catholic intelligentsia. As Gottfried explains, “fascists attempted to release energies and impulses that older Christian standards of behavior and later reformist social models tried to suppress or root out.”

It is also worth noting that neither Trudeau nor anyone else in Quebec’s elites went as far as Liberal Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who, in a 1937 trip to Germany, met Hitler and came away with this positive recollection.

… he is really one who truly loves his fellow man and his country … his eyes impressed me most of all. There was a liquid quality about them which indicated keen perception and profound sympathy (calm, composed)—and one could see how particularly humble folk would come to have a profound love for the man.

Yet no one accuses the naïve King of having latent Nazi sympathies.

It is true, as the Nemnis show, that Trudeau and other Quebeckers’ support for corporatism often complemented their hostility towards liberal democracy as well as their admiration for Pétain’s Vichy regime. These biographers are particularly outraged by the fact that young Trudeau read with enthusiasm La Seule France: Chronique Des Jours D’Epreuve (1941), a copy of which had been smuggled into Canada. Its author, Charles Maurras, was a famous representative of the anti-democratic right and pro-monarchist Action Française as well as a defender of the Vichy regime and Pétain. Trudeau was particularly taken with Maurras’s argument that the French Revolution was not truly French. The Nemnis explain:

Maurras, like his allies on France’s extreme right, and like so much of Quebec’s clerico-nationalist elite, believed that the real values cherished by the real French people could not possibly be those of the 1789 Revolution, or of the Republic, or of democracy, or of sordid aliens like the Jews and the Freemasons, or of those eternal enemies, the English. In this conflict opposing two standards, Marshal Pétain raised the standard of Christ, of “la vielle France.”

Trudeau did not share Maurras’s conspiratorial prejudices, nor did he endorse the Vichy regime’s collaboration with Nazi Germany. He also knew nothing about Vichy’s role in the Holocaust during the war. Yet he certainly did sympathize with Maurras’s disdain for democracy (and, by extension, the French Revolution). In fact, he cultivated this antipathy long before he started reading Maurras.

As a student at the prestigious Jesuit Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf in the 1930s, Trudeau read with enjoyment Alexis Carrel’s work, L’homme, cet inconnu (1935). The ideas of Carrel, a distinguished physician and scientist who won the Nobel Prize for medicine and physiology in 1912, deeply impressed the Jesuits and their students, including Trudeau. Although Trudeau did not endorse Carrel’s support for racial eugenics, he was impressed with Carrel’s attack on democracy. “The democratic principle has contributed to the undermining of civilization by impeding the development of the elite,” he wrote after reading the book.

In his notes from a course on constitutional law that he took in the early 1940s, Trudeau clearly listed the vices of democracy: “Ignorance, credulity, intolerance, hatred for superiority, the cult of incompetence, an excess of equality, versatility, the passions of the crowd, the envy of individuals.”

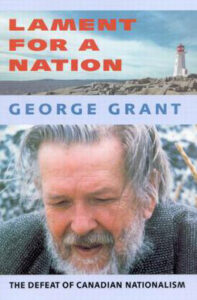

Once again, the question persists: does this animus towards democracy count as evidence of a deep sympathy for fascism? According to the Nemnis, the answer must be in the affirmative. Yet it is far from evident that this anti-modern traditionalism is inherently fascistic. The Canadian High Tory philosopher George Grant (1918-1988) held similar views about democracy, once remarking that leaders with a high “level of education and character” had no equivalent amid the “undiluted triumph of capitalist democracy.” As he explained in his famous treatise, Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism (1965), French Canada’s aversion to radical currents in modernity long predates the tumults of the 20th century:

During the nineteenth century, they [the French Canadians] accepted almost unanimously the leadership of their particular Catholicism—a religion with an ancient doctrine of virtue. After 1789, they maintained their connection with the roots of their civilization through their church and its city, which more than any other in the West held high a vision of the eternal. To Catholics who remain Catholics, whatever their level of sophistication, virtue must be prior to freedom. They will therefore build a society in which the right of the common good restrains the freedom of the individual. Quebec was not a society that would come to terms with the political philosophy of Jefferson or the New England capitalists.

Although the Nemnis know this history, they usually associate old Quebec’s admiration for pre-1789 France with latent fascist sympathies. They quote the clerico-nationalist historian, Lionel Groulx (1878-1967), on the blessings of the Ancien Régime: “We owe nothing to the blue, white, and red flag [of France]: it is the first, the fleur de lys flag, that we remember.” Groulx, whose lectures at the Université de Montréal were audited by Trudeau, opposed the domination “of Anglo-Canadian finance, of Anglo-American commerce, of Anglo-Canadian utilities, of American cinema, of suspect and cosmopolitan restaurants, gambling dens, songs, and radio.” Groulx also supported the ideal of maîtres dans notre province (masters in our own province) by promoting “l’Achat chez nous” (buy from us) boycotts of Jewish-owned stores.

While the Nemnis associate Groulx’s repudiation of “interlopers and cosmopolitans” with anti-Semitism and fascism, anti-cosmopolitan sentiment as a whole was arguably more deeply grounded in the historical memory of a colonized people anxious about its survival within English-dominated North America. As Grant explains in Lament, French Canadians have always struggled with the anti-national tendencies of Anglo-American liberalism:

The rights of the individual do not encompass the rights of nations, liberal doctrine to the contrary. The French Canadians had entered Confederation not to protect the rights of the individual but the rights of a nation. They did not want to be swallowed up by that sea which Henri Bourassa had called “l’américanisme saxonisant.”

Grant also called liberal democratic capitalism “the great solvent of all tradition in the modern era … including that aspect of virtue known as love of country.” In his youth, Trudeau expressed the same views as Grant: la survivance of Quebec in the face of “continental assimilation” was inseparable from its traditions, including its Catholicism. He even praised Quebec’s high birth rate, which was at least double that of English Canada in the 1930s.

Grant’s contempt for the “smirks and whimpers” of his fellow Anglo-Canadians who dismissed the identitarian aspirations of les Québécois went directly against a longstanding attitude among English-speaking progressives. As Peter Brimelow argues in The Patriot Game (1986), this attitude devalued any nationalism as “ultimately an uncouth, reactionary and probably racist atavism, valuable only as a demolition tool.” Trudeau himself later embraced this disdain for nationalism after he left Quebec to study politics at Harvard, the cradle of Anglo-American liberalism.

Although Grant scorned this English-Canadian elite for failing to develop a national alternative to American capitalism, he also correctly predicted that a more secular and leftist Quebec would fare no better. Ironically, during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, post-conservative Quebec followed the same pattern that English-speaking North America did. As Gottfried contends in After Liberalism (1999), Americans gave away “the responsibility of self-government for themselves and their polity, in return for what they value more, sexual and expressive freedoms of a certain kind and the apparent guarantee of entitlements.” In Quebec, a new social contract that celebrates bureaucratic statism and sexual permissiveness has replaced Catholic traditionalism.

(Wilfredo Rodríguez / Wikimedia, public domain)

The attempts since the 1960s of Quebec nationalists to repudiate the province’s reactionary past have not necessarily preserved the French-Canadian identity as a whole. Grant thought that this new managerial elite, which scorned old Catholic Quebec, was kidding itself with the assumption that nationalism and progressivism complement each other. As Grant observed, “the old Church with its educational privileges has been the chief instrument by which an indigenous French culture has survived in North America.” This High Anglican Tory had few doubts that the replacement of the old Catholic conservatism with secular libertinism and global capitalism spelled doom for French culture in North America.

The decline of the Church’s influence in Quebec has gone hand-in-hand with a birth rate that is lower than that of the rest of Canada. Deep anxieties over the survival of the French language and culture persist. Meanwhile, the Church does not seriously question the managerial state that holds its traditions in contempt. The “religion of humanity and progress,” as Grant once observed, has successfully overtaken even Catholic education. Brave souls who lament these developments in modern Quebec, however, risk being associated with love for a so-called fascist past.

Top image: Quebec City from Levis (Datch78 ; recadrage par Gilbertus, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply