“Country music is white man’s soul music.”

—Kris Kristofferson

“It doesn’t offend us hillbillies, it’s our music.”

—Dolly Parton on the term “hillbilly music”

“She sounds exactly like where she’s from.”

—Vince Gill on Dolly Parton

“The old ghosts are always rising up, refusing to be cast aside.”

—Ketch Secor

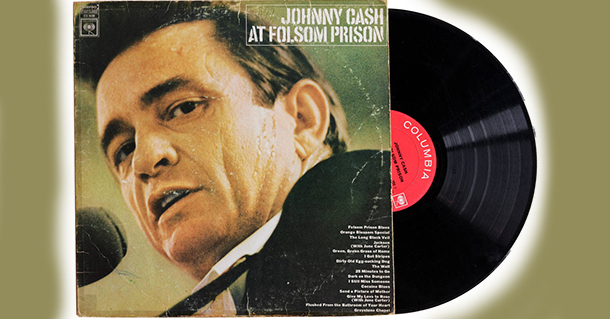

Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison was the first album I ever had of my own, a Christmas gift from my parents. I listened to that album over and over on the stereo my parents had given me that year, sprawled out on the floor of the living room of the little house my father had built on the outskirts of Houston, Texas, in the mid-1950s. I was ten years old.

Cash was my musical hero, and I learned every word to every song on that album. Momma and Daddy were very tolerant of me and my musical enthusiasms—the sound of Cash’s voice reverberated throughout the house all of that day and into the night. I ate my meals that day cross-legged on the floor, and soaked it all in. “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash,” Cash’s signature introduction line, was first spoken to the inmates of Folsom State Prison. That album covered all of the seemingly contradictory bases of Cash’s music: the prison song (“I’m stuck in Folsom prison, and time keeps draggin’ on…”); songs of tragic love and sudden death (“She walks these hills in a long black veil…”); songs of murder and retribution (“I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die…”); the working man’s lament (“It’s dark as a dungeon, way down in the mine…); and gospel songs (“Inside the walls of prison, my body may be, but the Lord has set my soul free…”).

Cash’s voice was thunderous, as if it emanated from the Burning Bush.

Decades later, his daughter Rosanne, noting the constant theme of sin and redemption in Cash’s music, said her father could sing “Folsom Prison Blues” and “Were You There (When They Crucified My Lord)?” at the same concert, with no one batting an eye.

Country music has always been an important part of my life. Before the stereo, I used a wobbly record player of my mother’s to play her and my older brother’s scratchy vinyl LPs, listening to songs recorded by Jim Reeves, Eddy Arnold, Bobby Bare, Marty Robbins, and Don Gibson, as well as by the Rockabilly legend who was Elvis Presley. Gospel was always part of the mix.

My carpenter father kept a small transistor radio in the Ford pickup he used for work, and I listened attentively to the “Rednecks, White Socks, and Blue Ribbon Beer” songs played on country music stations. Country singers in those days had names like Kitty, Loretta, Hank, Lefty, Faron, Merle, and my personal favorite, Ferlin. Ferlin Husky recorded a gospel tune that my mother particularly liked, “On the Wings of a Dove” (“On the wings of a snow white dove, He sends His pure sweet love, A sign from above, On the wings of a dove…”). My father favored the honky-tonk songs of Hank Williams, while my grandmother owned a collection of Bob Wills’ western swing records, each one as thick as a dinner plate.

At its best, country music tells stories, stories of hardship, tragedy, and faith, of rowdy Saturday nights, of repentant Sunday mornings, of elemental human darkness, of family and home, and of all the attachments that have grounded the people who made it. We could see ourselves in country stars like Hank, Johnny, George and Tammy, Merle, Buck, and Dolly. Waylon Jennings once said, “I’m as rough as a g-d— corn cob, and my voice comes from all that Texas dust” he breathed in as a boy. Merle Haggard’s songs expressed the occasional joy, and frequent sorrow, of his people’s Dust Bowl lives. I could read my own family’s history into songs like “Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” recalling Grandad’s Depression-era memories of hopping trains to the West Coast to look for work. When I heard Merle sing those songs in his rich, plaintive voice, the stories already seemed familiar to me.

My generation’s youth was spent during the rise of Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard as country stars, a period in which Patsy Cline died in a plane crash; Buck Owens introduced the raw electric twang of the Bakersfield sound; Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton wrote and performed their Appalachian story songs; songwriter Kris Kristofferson introduced his poetic lyricism to country music audiences; and Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and other outlaw country stars sparked a burst of innovative creativity as the so-called Nashville sound grew stale. That music became a part of us, an expression of our people and culture.

]When my mother passed away in 2015, we sang two of her favorite gospel songs, “In the Garden” and “How Great Thou Art,” at her funeral. My extended family, much diminished by time and scattered by the centrifugal forces of modernity, along with family friends and old neighbors, gathered once again. The family circle remained unbroken.

The music is ours, as much a part of our identity as a living, breathing blood relation, so I couldn’t help but experience a certain degree of trepidation when I heard PBS would air a Ken Burns documentary called Country Music. I figured our cultural commissars were about to diversify and inclusify the music of America’s core population, particularly descendents of colonial Americans, and we were in for another round of accusations of “institutional racism” and “white privilege.” Early on in watching the series, my fears seemed to have been materializing.

Burns almost lost this viewer by turning the foundational story of the music that came to be called “hillbilly,” then “country and western,” and, finally, “country,” on its head. For example, in the series’ first episode, “The Rub,” which references the mixing and tension between white cultural elements of country music and contributions from black musicians, Burns emphasizes the influence of black musicians on the development of country music. Black people did influence the evolution of country music, no doubt about it, but they influenced an already extant body of music, music brought to America by settlers from the British Isles. That settlement and the culture that accompanied it was the indispensable element in the origin of country music. Burns, however, seemed to be asserting that “the rub” was itself the genesis of country music.

To illustrate my point, consider this: Would PBS air a documentary on rhythm and blues music or black gospel that began by pointing out that the musical framework, the language, and, in the case of gospel, the themes of those genres originated with founding-stock Americans? The question answers itself.

What’s more, early on, Burns’ documentary makes the rather strained assertion that country music’s sources came from all over the world. Ray Benson, whose band Asleep at the Wheel has done so much to keep western swing music alive, reaches far afield to claim that country music has reflected “the immigrant experience.” (I forgive Ray, since he has been in Austin for decades, standing downwind from Willie Nelson.)

In another early sequence, veteran Nashville session musician Harold Bradley notes the importance of centuries-old ballads from the British Isles—of English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish origin—to country music, and dutifully says that it’s too strong to say “we” stole that music from “them”—“we” borrowed it. Yet the peoples he mentions were the American people at the founding. The shallow sense of American identity and the constant need to have others validate the music (evident in Burns’ documentary at several junctures, with rock musician Elvis Costello, for instance, chiming in to confirm Loretta Lynn’s talent to viewers) was exasperating. Once again, it seemed, descendants of colonial Americans were being portrayed as a footnote to their own history.

Nevertheless, I wound up liking Country Music very much.

First, with a few important corrections, the story that unfolds in the series is not wrong: Country music is a style of popular music that evolved out of various sources, beginning with Anglo-Celtic folk ballads and Protestant gospel singing as its foundation. Slaves introduced the instrument that over time became the banjo as we know it, a seminal contribution to the sound of country music. The work of American songwriters like Stephen Foster was an important influence, and white and black musicians borrowed from one another. Cowboy ballads became part of Americana music, and that music percolated in minstrel shows. By the 1920s, with the invention of radio, folk tunes and gospel songs were broadcast, then recorded by music pioneer Ralph Peer. The music Peer called “hillbilly” was popularized by the original Carter Family and “the Singing Brakeman,” Jimmie Rodgers.

From there, country’s musical styles branched off: cowboy music, as popularized by singers like Gene Autry; bluegrass, with Bill Monroe as its key figure (music historian Bill Malone, who is cited frequently by Burns, rightly says bluegrass is the closest to country’s roots, undermining the “we are the world” interpretation of country music’s origins); western swing, which became practically synonymous with band leader Bob Wills; honkytonk, the music of Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, and Lefty Frizzell; and rockabilly, the point where country, gospel, and rhythm and blues meld together (songwriter Bobby Braddock notes that if rhythm and blues was the mother of rock n’ roll, then “hillbilly was the daddy”).

Burns frequently subverts his own PC signals, perhaps unconsciously. In the first episode on “the rub,” for instance, Dolly Parton explains the foundational importance of the old ballads from the British Isles. In the Smoky Mountains, Dolly explains, before radio or television, those ballads were the stories her mountain folk gathered to hear. Those ballads of hardship and struggle, of love and tragic death, of kith and kin, represented a core element of country music’s origins that had been passed down for generations. The other indispensable element was music like the songs bluegrass musician Ralph Stanley heard in his Primitive Baptist church, and in the fields where his father worked and sang gospel tunes. Burns has Stanley tell that story himself—and sing it—in a deeply moving a cappella rendition of “A Man of Constant Sorrow.”

In a sequence on the success Ray Charles had singing country music in the ’60s, jazz musician Wynton Marsalis notes that “People think it was just white musicians listening to black musicians, but it was black musicians listening to white musicians, too.” Charley Pride, a black country singer from Sledge, Mississippi, dealt with his awkward mid-60s debut in front of a white audience by joking about his “permanent tan.” (The crowd loved his music.) Pride later became a close friend of established Nashville star Faron Young, a man not known for holding liberal views on race relations. Young became Pride’s biggest supporter in Nashville, and they were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in the same class of honorees.

More PC bubbles are burst in the episode that has the late ’60s, “women’s lib,” and Vietnam War protests as its backdrop. There is a somewhat lame attempt at casting the Coal Miner’s Daughter, Loretta Lynn, as a proto-feminist, but Lynn is quoted as saying she never thought she was part of any movement, and that her songs were just “about life,” not a political agenda. According to Lynn, “If you write about your life, it’s gonna be country.” Burns notes Johnny Cash’s vocal opposition to the Vietnam War, but also tells the audience that the Man in Black entertained the troops in Vietnam, and that 65 percent of the records sold on military bases in that era were country records.

Merle Haggard came into his own in that era as the “Poet of the Common Man,” challenging the counterculture with songs like “Okie From Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me.” In one astonishing sequence, given the times we live in, Burns quotes Haggard describing “Muskogee” as an anthem of pride: “Everybody wants to be proud of bein’ somethin’,” says Haggard, and in an obvious reference to the black pride movement of that time, goes on to say, “I’m proud to be black,” and without skipping a beat, adds, “I’m proud to be white. I’m proud to be an Okie.” Merle says that was something he figured would resonate with a lot of people, and it did.

Burns tops off the Vietnam-era sequence with country singer Jan Howard, who lost a son in Vietnam, telling war protest organizers who had come to her door that she thought they had every right to protest, but if they ever came around again, “I’ll blow your damn head off with a .357 Magnum.”

Bill Malone gets the politics of the music about right when he says that country’s attitude has always been populist. Merle Haggard, for instance, once said, “The little guy always gets screwed by the rich guy and the government.” As I noted earlier, Merle was a lot like the people of my own extended family, people who went West looking for work during the Depression, people who sent their sons to fight in America’s wars, people who were never wealthy and often dirt poor, yet they unreflectively, instinctively loved their country. Their patriotism and music reflected heartfelt attachments that were beyond rationalization or ideological formulas.

Country music’s sharp conservative turn in the ’60s, as Bill Malone correctly notes, wasn’t so much about support for the war as it was a protest against the protestors. It’s unfortunate that that conservative turn has, since Vietnam, so frequently translated “Support the Troops!” as “Support the War!” Haggard, who passed away in 2016, knew better, and he opposed the disastrous Iraq War. It’s not at all surprising that country music’s base audience voted for Donald Trump in 2016, a man whose personal life is certainly no messier than George and Tammy’s lives were.

Country music features outstanding segments on the life and times of Hank Williams (the “Hillbilly Shakespeare”), Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones and Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and “Bocephus,” Hank Williams, Jr., as well as on the evolution of bluegrass, western swing, honkytonk, rockabilly, and country rock. Country and bluegrass performer Marty Stuart stands out among the talking heads of the series, displaying not only his encyclopedic knowledge of all things country, but his virtuosity as a picker and his deep love of, and devotion to, the music.

Religiosity plays a prominent role in the series, and Burns is not shy about showing his audience just how at home gospel is in country music. In one moving sequence, Hank Williams’ granddaughter Holly speaks eloquently on the roots of Hank’s gospel hits like “I Saw the Light,” adding that she believes her grandfather truly “believed in the redemptive power of Christ.” We also hear about Kris Kristofferson answering an altar call at an evangelical church (his friends in Nashville had been encouraging him to go), and Kristofferson tells us that experience inspired him to write his biggest hit, “Why Me.”

Time and again, Burns notes that country music has come back to its roots when it drifts too far astray, smoothing out its rougher edges in the ’60s and ’70s, for example, with “Nashville Sound” and “Countrypolitan” productions that featured less hillbilly twang and more orchestration. In Episode 6, “Will the Circle be Unbroken?”, Burns also portrays Americana music as a unifier. Bluegrass, Burns notes, was revived in part because the college kids of the turbulent ’60s recognized its authenticity, and Burns portrays the generation gap of that era as being bridged by a love for the bluegrass sound. Burns also apparently believes the “circle” of a broken country can be mended by culture, and obviously sees country music as an important element in America’s cultural heritage.

Ken Burns turns out to be a rather naïve old-school liberal, a good-natured man not mean-spirited or spiteful enough to be “woke.” He really sees “the rub,” of black-white musical exchanges and the authenticity of Americana music as unifiers that can bring all of us together singing in a national “family circle” that will somehow be unbroken. Indeed, Burns uses the beloved gospel song “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” as a recurrent theme in the series.

It’s clear that Burns can’t help himself. He has real affection for country music and the people who make it, an affection for Americana that was evident in his Civil War series nearly thirty years ago. Burns’ attitude and approach has prompted some “woke” journalists to attack Country Music for being too kind to the hillbillies and the oppressive culture they supposedly represent. It may be that Burns’ critics sense what this viewer detected in Country Music: that Ken Burns’ latest documentary will not serve the Narrative well. It seems more likely that Country Music will inspire many viewers to learn more about Middle America’s heritage and creative past. How could anyone who feels affection for the music and people portrayed in Burns’ documentary really hate America?

In the final episode of Country Music, “Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’,” Burns highlights the tensions between creativity and tradition, and between commercialism and artistry in country music. Revered songwriter Guy Clark, who had so much influence on the musicians who pioneered outlaw and alternative country, once warned up-and-coming musician Rodney Crowell, “You can be an artist or you can be a star…pick one.” Yet Country Music depicts a number of instances when artists became stars, often in spite of the Nashville corporate machine. Cash, Haggard, Nelson, Jennings, and others, right on down to the “new traditionalists” of the 1980s like Dwight Yoakam, Ricky Skaggs, George Strait, Reba McEntire, and Randy Travis, bucked the homogenizing trends of their eras and managed to make music that was new and fresh, while remaining authentic and connected to country music’s past.

Country music has always stressed, in the words of a Merle Haggard tune, “the roots of my raising,” and whenever it has gotten “above” that “raising,” and disconnected itself from those roots, an artist appears who brings the music full circle. Country music, as singer/songwriter Tom T. Hall pointed out to Burns, doesn’t have to sound exactly the same at all times and all places, but as bluegrass musician Ricky Skaggs assured Bill Monroe when the old man was fading, Monroe had planted many seeds, and those seeds would carry on, drawing from the deep well of country music’s heritage.

The monumental voice and presence of Johnny Cash looms large in Country Music. Along with Hank Williams, Cash is portrayed as the face and spirit of the music itself. In his early years, Cash was among the group of young rockabilly performers who created a sound that was at once new, while remaining rooted in the musical streams it drew on. As his fame grew and he became a fixture in country music and in American public life, his personal life was in shambles, marred by the temptations of stardom and the destructive effects of drugs. Johnny Cash appeared to be on the same trajectory as Hank Williams, who died at 29, but by the grace of God and the influence of the most important family in country music, the Carter family, Cash survived and flourished. He was both a star and an artist, as well as a symbol of the hardscrabble culture he came from.

In the ’90s and early ’00s, Cash revived his faltering career with the help of an unlikely figure, hip hop and heavy metal producer Rick Rubin. It was Rubin who persuaded the aging star to make the American Recordings, a series of albums featuring a stripped-down, raw sound similar to that of Cash’s early days. Country music was again revitalized. Fall and redemption had been a constant preoccupation of Cash’s artistic life, and the old story played out again at the end of his earthly life.

In its final episode, Country Music tells the story of Johnny Cash’s artistic revival, and of his physical decline and death. He and his wife June Carter, whose family had been present at the creation of country music, had become the happy couple that George and Tammy tragically could not. Cash had reconciled with his oldest daughter, Rosanne, who had become a country music star in her own right. As he declined physically, he refused painkillers, so as not to fall prey to the addiction that once nearly destroyed him. Johnny Cash died with dignity in 2003, his reputation restored, his legacy secured, and just four months after June Carter passed away. He was 71.

At a Johnny Cash memorial concert held at the “Mother Church of Country Music,” the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, Rosanne took the stage to sing a song her father had co-written, “I Still Miss Someone” (“I miss those arms that held me, when all the love was there…and I still miss someone, I still miss someone”). The circle remained unbroken.

Johnny Cash was buried next to his beloved wife, June, and his gravestone reads:

Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord…

Image Credit: above: Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison record album from 1968

Leave a Reply