The Artist

Produced by Le Petite Rein and Studio 37

Directed and written by Michel Hazanavicius

Distributed by The Weinstein Company

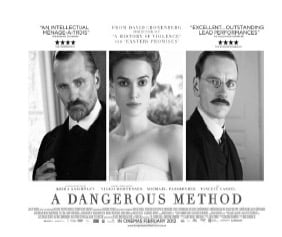

A Dangerous Method

Produced by Recorded Picture Company

Directed by David Cronenberg

Screenplay by Christopher Hampton

Distributed by Sony Pictures

As I write, many critics have declared French writer-director Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist the best film of 2011. I don’t know what “best” means when applied to a movie, but I will say this: The Artist is unquestionably the most beguiling film in many years, combining as it does Buster Keaton’s wondrous ingenuity with Fred Astaire’s effortless elegance.

The story couldn’t be simpler. Silent-matinee idol George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), studiously reminiscent of Douglas Fairbanks, suddenly finds himself eclipsed when sound films become de rigueur in 1929. He seals his professional doom by refusing to appear in a talkie. To do so, he implies, would be a breach of his art. In a sort of Star Is Born reprise, he’s shunted aside, while his protégé, a young actress amusingly named Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), easily adjusts to the innovation. She becomes, as they used to say, a box-office smash, while his fortunes decline precipitously. The storyline is self-consciously trite, just a scaffold on which Hazanavicius has built a highly entertaining meditation on his medium, recalling early responses to the sound film.

In 1929 Evelyn Waugh complained that “talking films . . . had set back by twenty years the one vital art of the century.” He was not alone. The German theorist of visual perception Rudolph Arnheim worried that sound would mislead filmmakers. In 1933, he sourly prophesied that the medium would sacrifice the artistic suggestiveness of the silents to the vulgar—and more profitable—realism to be had in making Technicolor, widescreen, three-dimensional talkies. We who have grown up with sound films might find such an aesthetic position theoretically interesting but hardly congenial. The accomplishment of The Artist is to beguile us into seeing Arnheim’s point of view.

Hazanavicius made this mostly silent, black-and-white film to remind us that the most seemingly realistic of entertainment media is built upon cleverly constructed illusions. He does so by calling our attention to the difference between life and artifice. In one sequence, Dujardin, playing an espionage agent, walks onto a set just before the cameras are to roll. He signals the director and cameramen that he needs a moment’s preparation. Bending forward slightly to assume an attitude of stealth, he sets his mouth in formidable resolution, arches a well-plucked eyebrow, and, as the camera begins to roll, steals across a dance floor crowded with formally dressed men and women. Before he’s halfway to the other side, however, he jostles a dancing couple. The woman, assuming he’s cutting in, turns into his arms and continues waltzing. He’s so delighted with her that he misses his cue to move on to his rendezvous with another spy. When he realizes his mistake, he turns to the director, shrugging with an apologetic smile. There’s a cut, and the scene begins again. He sets his face and leans into his walk. But once the young lady is in his arms again, he’s unable to leave her embrace in timely fashion. Two more attempts end in the same gaffe. The couple’s feelings are breaking up the artifice in which they’re engaging.

This sequence is a short essay on the difference between life and art. Art is calculated; life, headlong. A similar confusion between life and art occurs in the very first scene. Dujardin is shown in extreme close-up wearing headphones. He’s playing the role of a spy being held by Soviet secret police. They’re torturing him to reveal his espionage mission on their soil. Suddenly, electric current begins arcing into his headphones, and his face contorts with unbearable pain as he silently screams at the camera. A title card flashes: “I won’t talk.” A scene later, he’s on the other side of the camera refusing his producer’s request to make a talkie. No, he won’t talk. Later, at the end of a long dance with Bejo, we’re startled to hear the silent stars breathing heavily. With these and other scenes, Hazanavicius reminds us how artifice and life overlap in curious ways, a circumstance that’s better acknowledged than hidden, he seems to be saying.

I don’t want to suggest that The Artist is a cinematic lecture. Much of its appeal derives from its delightful performances, especially Dujardin’s. He plays Valentin as a rich comic slice of ham. He cannot do enough to please his audiences. At a premiere of his latest epic, he takes the stage after the film is over to accept the audience’s adulation. He smiles with a show of self-deprecation even as he ushers his co-star into the wings, the better to hog the limelight. But it’s impossible to hold this against him. His self-infatuation is the same thing as his compulsion to entertain. Besides, his smile is too genuinely engaging. He’s simply the reel thing.

While rather funny—unintentionally, at least—David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method exhibits few smiles. Based on Christopher Hampton’s deadly serious play The Talking Cure, it forcibly reminded me of what my late friend Jack Meehan used to say: “You have to be crazy to see a psychiatrist.” Of course, Jack was deeply Irish, a condition Sigmund Freud declared insuperably resistant to the ministrations of his science. It may be that the Irish haven’t an unconscious to explore. Or perhaps they think it inconsiderate to burden others, especially bearded strangers, with their troubles.

The film purports to dramatize the initial collaboration and subsequent falling out of Freud (Viggo Mortensen) and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) as they developed their psychoanalytic theories. Their association came to grief over a woman, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). It seems that these daringly radical pioneers of the soul’s heretofore unexplored depths were nothing less than conventionally bourgeois after all.

We meet Miss Spielrein as she’s being taken by horse-drawn carriage to Zurich’s Burghölzli clinic in 1904. She’s to be treated for hysteria. Miss Knightly alternately shrieks and cackles as she’s manhandled down the clinic’s corridors and dunked into a bathtub, the better to chill her exuberance. In my ignorance of Miss Spielrein’s history, it occurred to me the young woman was being extravagantly bratty, and more in need of spanking than dousing. I was completely wrong. My method would have been dangerous, indeed. Used as a remedy, it would likely have deepened her psychosis. Spanking was exactly what Sabina neurotically craved. For, as she shortly reveals to Jung as he psychoanalyzes her, when she was three she had found herself sexually aroused by her father’s spankings and frequently misbehaved in order to provoke more of them. And here is where the greater craziness steps in. As the analysis proceeds, Jung allows himself—far too willingly, it seems—to be maneuvered by Miss Spielrein into taking up the role of her spanking father. Quaint therapy, indeed! In waistcoat and tie, he slaps Miss Knightly’s bared buttocks with measured deliberation—first with his hand, and then with an alarmingly broad strap. His formal dress seems to indicate he thought he was performing a professional duty. Miss Knightly, less formally attired, accommodates him and us with a display of her breasts, accompanied by truly ecstatic moans. I’m obliged to report she’ll not soon win the Kate Winslet award for voluptuous display.

When Freud discovers Jung’s breach of professional etiquette, he sniffily takes the younger man to task. Having chosen Jung as his heir apparent, he now fears this Aryan will discredit the psychoanalytic movement. Earlier, he tells Jung that his nascent discipline has enemies. Why? Jung wonders. Because, Freud replies, he and so many of his followers are Jewish. What difference does that make? Jung asks. To which the Viennese doctor replies drily, “That is an exquisitely Protestant remark.” Freud had worried that his work would be dismissed as a Jewish science, and while the script does not say so, one wonders if he didn’t think Jung would help establish a degree of Christian respectability to his adventures in plumbing the unconscious. Perhaps Jung didn’t care to be a fig leaf.

I don’t know what Cronenberg intended, but I came away from his film thinking its principals would have been well advised to busy themselves with some manual labor rather than allowing their intellects the leisure to roam so promiscuously far from the staid reservation. Fassbender as Jung seems entirely oblivious to the possibility that his high-flown theories about repression are just a blind to facilitate his sexual transgressions, which he undertakes with a solemnity that seems entirely inimical to pleasure. Odd behavior for a man who in 1950 would write Pope Pius XII to commend his declaration of the dogma of the Assumption of Mary. Jung thought the doctrine was a welcome feminine correction to a sternly masculine conception of God. As for Freud, Mortensen has been directed to play him sardonically. He was, after all, convinced that there was no cure for human fooleries other than to take note of them, so as to live in a state of therapeutically sound disillusionment.

As a coda, the film closes with written statements of what the future was to bring to its subjects. What it brought to poor Miss Spielrein after her successful career in psychoanalysis was murder at the hands of the Nazis, who also killed her two daughters in 1942. They were judged guilty of being Russian and Jewish. Whatever silliness she may have gotten up to in her early years, her ending was, if not tragic, certainly pitiful. In light of it, Freud might be judged correct: Human beings are incurable. Only a sustained faith in the possibility of redemption can relieve the horror of this conclusion, but redemption was precisely what Freud dismissed as childish imagining. As a therapist, Sabina had sought to help her patients to a this-worldly redemption. She had hoped like Jung to enable them to become “the people they were meant to be.” When she told Freud this, he gently scoffed, “What good can we do if we replace one delusion with another?”

And for such cold comfort, people are charged $120 per hour? Scotch is a good deal cheaper and more enjoyable.

Leave a Reply