Nineteen eighty-eight is the centennial year of T.S. Eliot’s birth, and there is sure to be a flood of tributes to a writer that has changed the course of poetry and criticism and whose reactionary pronouncements on politics and religion have been an inspiration to conservatives of every description. Instead of offering to Mr. Eliot a series of analytical essays exploring his contribution, we are presenting a set of essays—some of them, indeed, on Eliot himself—he might have enjoyed. The two feature essays are the Ingersoll Prize addresses of Octavio Paz and Josef Pieper, both of whom pay tribute to the poet, critic, and philosopher whose works continue to challenge the spirit of the age. This month’s perspective was delivered as an address on the occasion of the 1987 Ingersoll Prizes Banquet at the Drake Hotel in Chicago on 5 November.

A Victorian gentleman who happened upon our age by accident would be delighted, in many respects, by what he found here. All the conveniences of life on which men were wont to speculate 100 years ago, we have in superabundance—air ships, undersea boats, devices that send pictures and voices across the globe, and expeditions mounted to explore the solar system. Our proper Victorian would no doubt smile into his beard—delighted that his trust in science had been justified after all.

Indeed, science has transformed the world, but the transformation is more than the bric-a-brac of skyscrapers, miracle drugs, and the science-fiction devices that disturb our quiet. We often hear of modern man’s Faustian pact with science. But the author of Brave New World, Aldous Huxley, found a more accurate parallel in Shakespeare’s Tempest. In that play, Prospero the magician has created a marvelous world, a life of ease charmed by hidden voices, but he has had to rely upon the witch’s son, Caliban, a resentful and rebellious servant we might just as well name Technology. Like Prospero we moderns work wonders, but also like him we risk being deposed and displaced by our subhuman servants. We have changed the face of the world and made it reflect our aspirations. Even time has not resisted our efforts.

We live in a universe of time and space quite different from the world inhabited by either the ancient pagans, who saw time as a wheel, or the not so ancient Christians, who looked towards eternity. As Octavio Paz has written in his most recent book, “The civilization of progress has situated its geometrical paradises not in the world beyond but in tomorrow. The time of progress, technology, and work is the future. The time of the body, the time of love, and poetry is the present moment.”

This was not the first time that Mr. Paz has coupled love and poetry in opposition to progress and technology. It has been the aggressive spirit of scientific inquiry that has invaded sphere after sphere of the human spirit. The rewards have been enormous, not only in all those little conveniences of life we have learned to take for granted, but even more in our understanding of the mechanics of the creation. For the first time, we may be in a position to trace the origin of life and of the universe itself. Our scientific studies of the human species and its nearest relatives may soon reveal the secrets of human society, the how and why of power arrangements, the rules of family life, the principles behind all forms of good government.

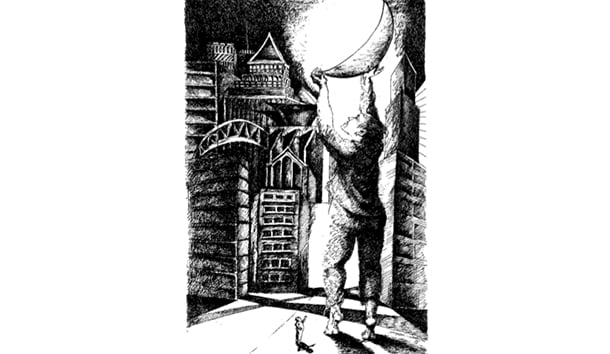

But there is always a price for these advances in human understanding. Like miners in pursuit of subterranean gold, we have turned blooming landscapes of the spirit into slag heaps as poisonous as they are ugly. In our relentless search for knowledge, nothing is spared, nothing is sacred, not even that inner man or woman we think of, from our earliest years, as our real self. Beginning with Freud’s first crude attempts, our dreams and unconscious urges have been dissected, classified, and exposed to public comment. Most recently a new self-awareness cult has arisen around the dream, which can now, it seems, be artificially stimulated and exploited for profit and career advancement. There is nothing in our human experience that is to be left unviolated. Readers of Shakespeare will remember that Caliban’s crime was his attempt to rape the magician’s daughter, a pure and naive virgin.

It is in this context that the giants of modern poetry must be read and understood, as soldiers and rebels in a war for man himself—his soul and mind of course, but also for his imagination and even his body. In such a war strange and unpredictable alliances are made, and we sometimes find ourselves fighting shoulder to shoulder with men we have denounced as our worst enemies. How many sermons have been preached against Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the few men who understood the calamity that modern man was bringing upon himself. How much ink has been spilled by traditional critics lamenting the vulgarity of Baudelaire, the obscurity of Mallarme, the free verse of T.S. Eliot. Indeed, the two American intellectuals closest to Eliot, Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More, were both distressed by his poetry, although it was Babbitt who resorted frequently to the phrase “moral imagination” as a means of explaining the serious role played by literature.

It is only in the best poetry of our century—the work of Yeats and Rilke, Eliot and Valery, and of Octavio Paz—that the human imagination reasserts its full strength in rebellion against all the political and technological forces that would turn us into mere animated computers. It is particularly fitting that a poet should receive a prize named in a poet’s honor, and even more so, since Mr. Paz is among the few living poets strong enough to wear Eliot’s mantel.

As a social thinker and essayist, Octavio Paz has evolved from a self-proclaimed rebel to a still-rebellious opponent of the political revolution that threatens to turn the world into one vast concentration camp. But for all the virtues of his political essays—especially his brilliant observations on this flawed Utopia called America—his real contribution has not been as journalist or philosophical essayist, but as one of those rare explorers of the imagination.

In his poetry, Mr. Paz has continued the work of the surrealists. Like all movements with manifestos and theories, surrealism was destined to destroy itself—how can you prescribe rules for the unconscious mind? But at their best, surrealist poets like Andre Breton offered a challenge to all the little philosophies and pseudosciences which attempt to describe man from the outside in. Real life, the life of poetry and love, is hidden at the center of our existence, impervious to probes and analysts, and it is this real life that Octavio Paz has been exploring in a poetry that has transformed the Spanish language and—for his many readers—has helped to give man back to himself.

It is the real man, the man of imagination and moral choice that is under siege these days. In place of the living, breathing human beings making choices, taking risks, and accepting consequences, the technological view of man has given us so many machines that can be programmed and tinkered with: economic man, sociological man, psychological man, and political man; man the oppressor and man the oppressed; man the capitalist, man the socialist; and above all the modern man and the antiquated man. Estranged from history and each other, we hear a term like “moral imagination” and it strikes our ear like an antique or foreign phrase, now that both morality and the imagination are reduced to psychological phenomena.

A number of philosophers have attempted to recover something of the older sense of moral virtue and human responsibility, but none has worked so tirelessly as Josef Pieper. It is hard to estimate the impact of Dr. Pieper’s work. I well remember one of my Greek professors, back in the late 1960’s, lending me what he called “an absolutely extraordinary book.” That book was, of course, Josef Pieper’s Leisure the Basis of Culture. It was my wife who lent—or rather gave, since I have never returned it—Pieper’s splendid little book on scholastic philosophy. What, I asked my wife, can a man say about scholasticism in so brief a treatment. The answer turned out to be, “more than most intellectual histories that encompass thousands of pages.”

There is no living philosopher who writes of such serious topics—virtue, hope, the difficulty of belief, cultural decadence—with Pieper’s combination of scholarship and humility. Resisting the temptation to be merely original and refusing to fall into pedantry, he has returned philosophy to that serious but lively conversation in which Socrates and his friends engaged so many years ago.

The object of true moral philosophy has always been man as he is, with all his frailties and timidities, and not the Promethean or Utopian man of political dreamers. The great moralists of the past—Aristotle, Cicero, St. Thomas, and Samuel Johnson—all had this in common, a willingness to face the facts about the human race without despairing, and it is to that company that Josef Pieper belongs.

Undeterred by the propagandists of the Third Reich, he wrote his first book to show the impossibility of courage without justice; and equally undeterred by other propagandists, who tell us we have nothing to fear but fear itself, Pieper has patiently explained that fear is not only part of the human constitution, it is also a gift that leads us closer to a sense of reality and, ultimately, to God. “Ethical good,” he writes, “is none other than the development and perfection of the natural tendencies of our nature: it is man’s natural fear of the diminution and annihilation of his being; its perfection lies in the fear of the Lord.”

Fear is as much a part of our nature as love and courage, but the diminution we have most to fear in our time is not mere death, but the mortification of our very being, the hardening of our hearts, the erosion of our imagination, the institutionalization of what our spiritual ancestors called sin. In very different companies and with very different weapons, the two men celebrated by the 1987 Ingersoll Prizes have helped to lead the counterattack against all the forces of dehumanization.

Leave a Reply