Publishers Weekly must be the most depressing magazine published in the United States. Oh, there are others like Esquire that make us despair for the affluent numskulls who swap life-styles as if they were wives, or The New Yorker that makes us remember how really boring New York can be. But for the sick feeling in the stomach that threatens paralysis, the feeling Augustine must have had as he began the Civitas Dei, you must try the premier magazine of the book publishing industry. From the full-page ads promoting “A New Self-Help Profit Maker” by best-selling author L. Ron Hubbard, to news stories on Anna Porter’s acquisition of 51 percent of Doubleday Canada or the copublishing plan of Basic Books and The New Republic, to interviews with industry leaders (“retailers and publishers are moving more toward making nonbook products available for consumers”), all the way to the back where we find names like Stephen King, Pat Conroy, Jackie Collins, Danielle Steel, Bill Cosby, Andy Rooney, Jim McMahon, Carol Burnett, and Robert Schuller. What do they all have in common—apart from fame, fortune, and bad prose? They all have top-15 hardcover best-sellers in the first week of 1987.

Please do not misunderstand. Publishers Weekly is a solid trade magazine. It can hardly be held responsible for what goes on in the literary marketplace, but many a writer and reader glancing through its pages must have asked themselves, “What is the point to universal literacy, if the novel of the week is It and the nonfiction best-seller is ‘Dr.’ Bill Cosby’s ruminations on fatherhood?” (By the way, ask Dr. Bill, next time you run into him, how he earned his degree.)

If we turn from humble best-sellers to “PW‘s Choice: The Year’s Best Books,” there is some improvement but not much. Reynolds Price, Peter Taylor, and Mary Lee Settle are all mentioned, but so is Margaret Atwood. The nonfiction category, oddly enough, displays a high degree of professional courtesy, with books on Ed Murrow, Emily Dickinson, and Hollywood screenwriters, to say nothing of George Plimpton’s anthology of Paris Review interviews, Writers at Work. It’s a tough choice between the lowbrow Andy Rooney and the middlebrow Ed Murrow, but on balance, the best-seller is less offensive.

There is, to be sure, a place for popular fiction and popular history. Chesterton was not the only writer who has enjoyed “penny dreadfuls,” but ours cost something like $22.95; and dreadful doesn’t begin to describe the moral, intellectual, and artistic qualities of Ms. Steel or Rev. Schuller. America is the land of opportunity where citizens are free to choose, but increasingly readers of new books are free to choose between the sentimental garbage of soft-core sex gothics and the more pretentious garbage of Frederick Barthelme (not to be confused with Freddy Bartholomew) and Philip Roth. Why?

Those who delight in conspiracy theories will point to the interlocking directorates of American mass media. How easily executives and journalists shuttle back and forth between highbrow magazines (The Atlantic), middlebrow papers (the New York Times), and browless advertising circulars (Newsweek). The career of Gordon Lish is instructive: Lish, a self-described novelist, has worked for Esquire, Knopf, and Yale. For promoting the careers of some of the silliest and least-read writers in America, Lish has received awards both from the American Society of Magazine Editors and from the Columbia School of Journalism. Multiply Lish by a few hundred, and you have the American publishing industry, a cozy little cabal of self-promoters who dictate the reading tastes of 200-plus million people.

I wish it were that simple—so does Gordon Lish, one imagines—but the only conspiracy in all this is the conspiracy of mediocrity, of bustiers who regard the appetite for books as a kind of predisposition to drug addiction: The secret is how to find the best varieties of dope that will maximize consumption without killing the addict. Of course, they do push their own tastes. George Gilder and Kingsley Amis have both learned recently that feminists have an effective veto over New York publishing houses, and William Donahue’s splendid book on the ACLU saw the light of day only because Aaron Wildavsky brought it to the attention of Transaction. Still, they couldn’t prevent William Buckley from becoming a best-seller, and they were probably too stupid to realize the significance of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, a book that has planted the seeds of reactionary Christianity into the minds of millions of adolescents who read it—time after time—in the 1960’s.

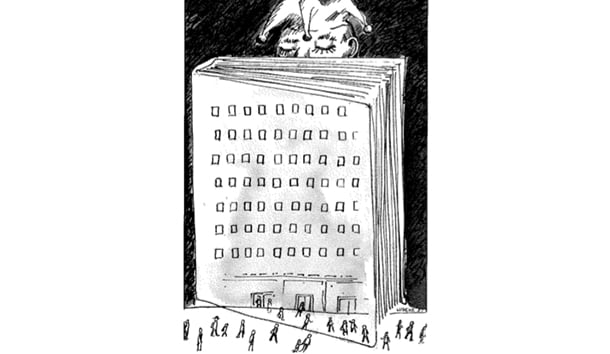

It is really very easy to understand the book business. All you have to know is a few facts: First, that anything printed between covers can be called a book and that the person whose name appears on the cover is the author. In this sense, Jane Fonda, Jim McMahon, Bill Cosby, and Andy Rooney are “authors” of “books.” Second, that mass literacy is really mass subliteracy: The American system of public education guarantees the right of every child to read on the fifth-grade level. A few go beyond that but not far enough to influence the publishing business whose only object is to put as many fifth-grade books in the hands of as many fifth-grade readers as possible. This leaves the business of “literature” (as opposed to mere “books”) safely in the hands of the mutual adoration society of critics and writers who read on the eleventh-grade level.

Perhaps the problem lies in mass literacy itself There used to be a vigorous illiterate culture in Europe and America—ballads, tales, and memorized Bible verses—that was far superior to the print culture of the 20th century. “Edward” can still scare the pants off anyone who hears it for the first time, and who has not wept over hardhearted Barbara Allen or admired the heroism of Sir Patrick Spense and Johnny Armstrong? Those days are, of course, long gone, and one of the joys of literacy is being able to read the folk culture of other times.

Still, in this electronic age, an illiterate culture of movies, TV, and pop music occupies more of our time than book publishers like to consider. John Updike is the most important novelist in America—or so we’ve been told—but his name rings a bell with scarcely a tenth of the population. The creative geniuses who really influence the country are people like Clint Eastwood, Merle Haggard, and Phil Collins. The genuinely mass markets of pop culture must be harder to manipulate than the book trade. How else do we explain the success of Dirty Harry and Death Wish?

The change in American literacy is most apparent in serious magazines. Back before World War I there was a class of readers (not simply scholars and intellectuals) who could be relied upon to subscribe to publications like Scribner’s, Century, and The Nation. Fiction and literary essays predominated, but there were articles on history, art, and even philosophy. The most interesting was The Nation. Founded by E.L. Godkin in 1865, The Nation was edited by Paul Elmer More in the prewar years. A scholar and philosopher, More expected his readers to follow a philosophical argument and catch a classical allusion. Without excluding political questions, he refused to pander to the taste for muckraking and issues-oriented journalism that was already seeping into other magazines. Because it was read by teachers and journalists, The Nation exercised an influence far beyond its 6,000 subscribers. To compare More’s magazine with what is turned out by Victor Navasky and Alexander Cockburn, the current reigning intelligences at The Nation, is an effort that numbs the imagination.

What most readers not working for the KGB find offensive in the present version of The Nation is the Stalinoid hard-line of Mr. Cockburn, but is The Nation really more ideological than its competitors? Hardly. Nearly every important magazine has a line to push, with friends in or out of power to defend. This in itself would not constitute a serious problem if the magazines did not devote most of their pages to titillating articles about Sandinistas (or contras) and the do’s and don’t’s of SDL. One year it’s religion, the next year it’s the family, and before long it will be “cultural conservatism” or the return of compassion. The manufactured issues change; sometimes a manufacturer switches sides, but a Rip Van Winkle who slept through the past 10 years would wake up to find he had missed very little in the way of news. (I once gave up television, newspapers, and magazines for several years. While I missed most of the Watergate coverage, I managed to read a lot of anthropology. Believe me, Mr. Nixon would have received fairer treatment in a pygmy band!)

To be fair, one has to concede that political journalism does supply a real need in American life by answering the question: How can an aspiring writer get a piece of the action? It has sometimes seemed that the only arts in which Americans really excel involve snookering each other. The Yankee peddler was our first symbol, the medicine show our first native art form, and advertising our greatest contribution to the world’s culture. Until the 20th century, it was hard for the literati (and the far more numerous subliterati) to find their place at the trough. In his essay “On Being an American” (written in the Harding Administration!), Mencken commented on “the doctrine that it is infra dignitatem for an educated man to take a hand in the snaring of this goose.” On the contrary, he insisted, any man with “the intelligence of a stockbroker and the resolution of a hat-check girl . . . can cadge enough money, in this glorious commonwealth of morons, to make life soft for him.” Mencken shared more of the American vices than he liked to admit, but in this case he proved himself to be a prophet. A few years later he was ridiculing the newfound professionalism of the “Babbitts turned Greeley” with their journalism schools, codes of ethics, and press clubs. It was only a matter of a few years before the old-fashioned reporter turned into a new-style journalist like Tom Wicker, whose novels read like columns and whose columns are as true to life as the latest Danielle Steel.

In the case of Mencken himself, political commentary provided a lucrative career for a literary essayist. In this respect, he was the heir of Swift and Defoe. But Mencken’s successors in “the profession” are more like the heirs of P.T. Barnum whose declaration, “There’s a sucker born every minute,” has made every political journalist an eternal optimist.

It is not that there is no place for political journalism, but its proliferation—at the expense of all humane learning—reflects the increasing vulgarization of life in the 20th century. Outside academic journals and the little reviews, it is hardly possible to read about any serious question unless it comes to us in the motley dress of a politician. Science is reduced to genetic engineering and textbook controversies; religion and theology are whittled down to the “wall of separation” and the Pat Robertson candidacy.

History, perhaps, fares the worst. It is hard to think of a widely reviewed book of history that was not aimed at some current political issue. In the ease of poetry, it is probably better not to discuss that subject in polite company, but how are we to explain the respectable status of Mr. Ginsberg, surely the most prominent political poet since Pope? If Ginsberg has ever written a line that is neither mawkish nor obscure, I challenge anyone to point it out. And yet this “grotesque essence” has to be discussed, has to be taken seriously because he chants (through his nose) “of arms and the man” (preferably the latter, it seems). A man of letters who wants to make his way in the world surely cannot afford to ignore the Ginsbergs, Mailers, Roths, Sagans, and Wickers of this world, no matter how much he recoils in instinct from their drivel; and while he might wish to take the high ground with Paul Elmer More, he may soon find himself on the level of Walter Lippmann, writing windy discourses on the American destiny. The position of a serious-minded journalist becomes as paradoxical as a police informant in a drug ring: The more he wants to correct the abuses in “the profession,” the more he is compelled to participate in the degradation. Before too long he’s hooked both on the money and the drug (cocaine or celebrity). More than one aspiring young conservative pundit has ended up part of the problem. Old men shake their heads and mutter, “A boy’s will is the wind’s will” and let it go at that.

Most of what we call polities is simply stupid, of little interest to grown men and women. The competition of one set of greedy rascals against another only rarely results in an important national election (1980 is an obvious exception). The trouble with The Nation in its present form is not so much its politics—who really takes Cockburn seriously?—but the triviality of its political obsessions. In some respects. The Nation is actually better than its more softhearted competition. There are occasional good pieces by film critic Andrew Kopkind and literary essayist Arthur C. Danto. (Once in a blue moon Galvin Trillin is half as funny as he thinks he is.) Christopher Hitchens is often good, but he is better in the Times Literary Supplement (London), where there is less of a party line. The attempt made by “responsible liberals” to read The Nation out of the world of polite discourse is as much a work of intellectual thuggery as any of Mr. Goekburn’s columns. In fact, the decline from More to Navasky is not that much more precipitous than the skid of other established magazines—although The Nation had farther to go. The New Republic began publishing in 1914, just as Paul Elmer More was leaving The Nation. The conjunction is significant, since TNR quickly took the lead in the issues-and-advocacy journalism that developed a mass market among the half-educated products of government schooling. Better than anything, the news and opinion magazines symbolize the triumph of general education.

The fruits of mass literacy can be observed everywhere, but it is only when we converse with teachers that we realize what harm has been done. An average high-school teacher is a college graduate possessed of at least ordinary intelligence. Since it is the teachers’ business to impart ideas and information, we expect them to be at least resident aliens in the realm of letters. But on the rare occasions when they talk about books, what do they mention? The women seem addicted to drugstore romances and the men typically fall for productions like Iacocca, Megatrends, or the latest Robert Ludlum. There are (or used to be) distinguished exceptions in nearly every school. However, as a class, teachers have learned nothing worth knowing, by and large, and (what is worse) they will never learn anything, because they are locked into a mass marketing scheme in which issues and ideas are so many brand-name products to be advertised on Ted Koppel’s Nightline or the Today Show.

The most obvious remedy is to give up on mass literacy or to write anything of value in Latin. Now, more than ever, we can agree with Edmund Waller:

Poets who lasting marble seek

Must carve in Latin or in Greek.

There is at least as large an audience for serious poetry in Latin as for English. Failing a second Renaissance of the classics, we might come up with new labels for what the book trade puts out. After all, the American Dairy Association has protected the consumer’s interest by restricting the word cheese to cheese. Everything else is a processed cheese product or a nondairy cheese food. Why not use “processed book-like product” for the novels of Philip Roth and nonliterary book matter for Dr. Bill Cosby’s Fatherhood. Perhaps The National Endowment for the Humanities could be given authority for administering a Federal truth-in-labeling law for the literary marketplace:

Warning: the enclosed literature-surrogate-material by Carl Sagan could be injurious to the IQ and prose style of public school graduates. Use only with caution under the direction of a competent scientist or theologian.

Something like that. The NEH would be performing (perhaps for the first time in its history) a really useful service. We might even let them hang around after the revolution.

Leave a Reply