The Forbearant Hero

Prior to the July 1863 march into Pennsylvania that would lead to the fateful loss at Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee instructed the battalions of the Army of Northern Virginia to remember

that we make war only upon armed men, and we cannot take vengeance for the wrongs our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of all those whose abhorrence has been excited by the atrocities of our enemies, and offending against Him to whom vengeance belongeth.

For the most part, the soldiers obeyed his exhortation, and Lee himself, upon establishing temporary headquarters near Chambersburg, refused to commandeer a private house but instead pitched his tent in the field among his men.

In later years Lee wrote, “The forbearing use of power does not only form a touchstone, but the manner in which an individual enjoys certain advantages over others is a test of a true gentleman.” Forbearance is a moral principle from which Lee rarely if ever wavered, and his unflinching practice of that virtue is, more than anything else that might be said about the great man, the primary reason that he should be remembered today. This is especially so if we understand forbearance to mean not only the restrained use of power, but also kindness, patience, and, most of all, self-control.

It is undoubtedly the case that Lee always enjoyed “certain advantages over others.” His parents were the offspring of two of Virginia’s first families. His mother, Anne Carter, was the great-granddaughter of Robert “King” Carter, a speaker in the Virginia House of Burgesses in the 1690s and, later, a colonial governor. His father, Henry “LightHorse Harry” Lee, was a hero of the Revolutionary War. Young Robert’s earliest years had been spent at Stratford Hall plantation in Westmoreland County, the seat of the Lee family since 1717. But his father’s debts, accumulated through unwise speculation, forced the family to abandon Stratford Hall and move to Alexandria in 1811. A year later, Henry was forced to flee the country, settling in the West Indies. Anne and her five children (Robert being her fourth) survived largely on the charity of William Henry Fitzhugh, a kinsman of the Lee family.

In the absence of his father, much family responsibility fell upon Robert’s young shoulders. His mother was “slipping into chronic invalidism” due to a variety of health problems, according to Lee’s principal biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman. But Lee accepted such burdens uncomplainingly. He was deeply devoted to Anne, who had shown an enduring determination that her husband’s “grim cycle of promise, overconfidence, recklessness, disaster, and ruin should not be rounded in the lives of her children.”

For Anne, “Self-denial, self-control, and the strictest economy in all financial matters were part of the code of honor she taught [her children] from infancy,” Freeman wrote. Such was the code that formed the foundation of Lee’s personal morality for the rest of his life, to which he added the Christian virtues of forgiveness and humility.

Lee’s first formal education was undertaken at Eastern View, a private school for boys set up by the Lee and Carter families. After a few years, he entered the Alexandria Academy, where he completed the conventional classical education of the day. Eventually, he decided to follow in his still-revered father’s footsteps and embark on a military career. He was fully qualified academically to gain entrance at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, but admission was difficult. With some assistance from Fitzhugh, he was able to obtain an interview with the Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun. Calhoun was sufficiently impressed with the young man to grant him a probationary appointment in the fall of 1825.

Life at West Point was austere, and Lee’s studies were focused on engineering, mathematics, chemistry, drawing, French, constitutional law, geography, history, ethics, and rhetoric. Robert excelled at all of these, though he was most drawn to mathematics and engineering. While he had little time for extracurricular reading, he did at one point acquire a copy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions, perhaps at the suggestion of his French instructor, Claudius Bérard. What Lee made of Rousseau is unknown, though one imagines he may have found the French philosopher’s almost exhibitionistic preoccupation with self-revelation distasteful.

Also among his professors was the distinguished jurist William Rawle, a Pennsylvanian and the author of A View of the Constitution of the United States of America (1829), a book that formed the basis for many of Rawle’s lectures. It is likely that cadet Lee became quite familiar with Rawle’s view that the Union was not a compact into which the states had entered irrevocably. Rawle wrote:

It depends on [the state] itself whether it will continue a member of the Union. To deny this right would be inconsistent with the principle on which all our political systems are founded, which is, that the people have in all cases the right to determine how they will be governed.

Lee’s early years of service in the Army were conventional enough. His undoubted talents as an engineer meant that most of his assignments would involve the repair and building of fortifications, first in Savannah, then at Fortress Monroe, near Hampton Roads. During this same period he pursued the hand of Mary Custis, the belle of Arlington House, a home constructed by her father, George Washington Parke Custis, an informally adopted grandson of President Washington. Mary would eventually become her father’s sole beneficiary, inheriting Arlington and its slaves.

Robert E. Lee at age 31 in 1838, then a young Lieutenant of Engineers in the U. S. Army

(oil painting by William Edward West / public domain)

Lee’s pursuit of Mary had little or nothing to do with her wealth or social preeminence. He had fallen for her years before—enamored of her wit and her strength of character—and had courted her assiduously, in large part against the preference of her father. They were married in June 1831, and would produce seven children.

Between 1831 and the outbreak of war with Mexico in 1846, Lee distinguished himself in a number of assignments, including a stint in Washington, D.C. as assistant to the Army’s Chief of Engineers, General

Charles Gratiot. The appointment was certainly a feather in Lee’s cap, though he had no love of office work. Still, he now had a growing family, and the post in Washington allowed him to devote more time to his domestic affairs.

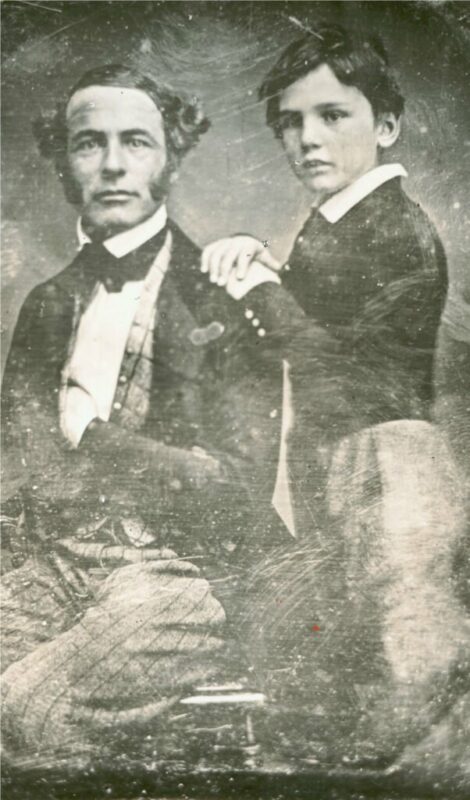

Robert E. Lee, around age 38, and his son, William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, around age 8, circa 1845

(photo taken by Michael Miley / Encyclopedia Virginia)

Every task that Lee undertook won him plaudits. By 1844, his reputation drew the attention of General Winfield Scott, who had recently become the commanding general of the Army, and it is likely that Scott, in 1846, had a hand in having then-Captain Lee transferred to his command in the campaign against Mexico. This was the first major turning point in Lee’s military career prior to his decision to take up arms against the Union in defense of Virginia.

The goal in the Mexican campaign was, first of all, to secure the disputed territory north of the Rio Grande, and then to pursue and destroy the army of General Santa Anna. This was no easy task. American forces had not engaged in major combat since the War of 1812, and the Mexican terrain was unfamiliar—a situation well suited to Lee’s reconnaissance and engineering talents. Lee quickly became part of what Scott called his “little cabinet.”

Beginning with the siege of Veracruz, where he was initially given command of an artillery battery, Lee became “the eyes and ears” of General Scott. Frequently exerting himself without sleep for days to the point of absolute fatigue, Lee organized reconnaissance missions deep into enemy territory through the treacherous ravines of Plan del Río, southeast of Mexico City. In preparation for the final assault against General Santa Anna, Lee proved indispensable in maneuvering the American battalions through the complex terrain around the capital.

Scott’s reports on Lee’s conduct were effusive. By the end of the campaign, Lee had received three promotions, returning home as a Lt. Colonel. Those who imagine that Lee’s later successes in Virginia in 1861–63 were due largely to the abilities of generals like Stonewall Jackson or J.E.B. Stuart should study Lee’s record in Mexico, which shows clearly his strategic and tactical brilliance, as well as his daring and supreme self-control. Late in 1857, as the political crisis between the North and the South was reaching a fever pitch, Lee lost his father-in-law and his wife’s health took a turn for the worse as she suffered from crippling arthritis. Through 1858 and much of the following year, Lee took successive leaves of absence to settle the complicated financial and legal matters required by his father-in-law’s will and to care for Mary just as he had done for his mother many years before. One could cite many such instances in which he displayed a willingness to place the needs of others above his own.

Even as he worried over family matters, Lee expressed deep concern regarding the talk of secession, which was spreading on every tongue. To his eldest son Custis he wrote, “The Southern states seem to be in a convulsion…. My little personal troubles sink into insignificance when I contemplate the condition of the country, and I feel as if I could easily lay down my life for its safety.”

Lee was a child of the old Republic, and he had expressed privately on a number of occasions that he was opposed to secession because he feared that it could only end in grief and disaster. Indeed, on the eve of the Civil War, according to Freeman, Lee had no belief in the unity of the South. His loyalties were for Union and Virginia. As it turned out, when those twin loyalties were brought into opposition, he did not long hesitate to declare his supreme devotion to the latter.

In another letter to Custis early in 1861, after South Carolina had declared for secession, he opined that “a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonet … has no charm for me.” Still, he was prepared to make any sacrifice for the preservation of the Union, “save that of honor.” He said much the same thing in his own defense when he met for the final time with his old mentor, Winfield Scott, in Washington.

The newly elected President Abraham Lincoln had offered Lee, still only a colonel, command of the Union army, comprised at that time of some 100,000 men. Had he accepted, this appointment would have been the pinnacle of his career—everything that he had worked toward for more than 35 years as an officer. But he could not take up arms against his native state and all the complexities of consanguinity that she represented. “I did only what my duty demanded,” Lee said after the war. “I could have taken no other course without dishonor.”

After Lee was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June of 1862, his achievement in the field silenced all those who may have doubted his ability to take decisive action. Beginning with the victory at Gaines’ Mill, he proceeded to rout Union forces at Second Bull Run and at Fredericksburg in 1862. In 1863 at Chancellorsville Lee achieved another astonishing victory, even after Stonewall Jackson was killed by friendly fire.

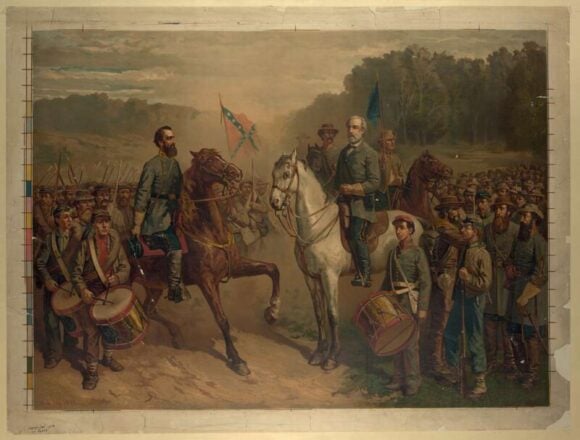

Robert E. Lee (right, on horseback) and General Stonewall Jackson (left, on horseback) meet for the last time before Jackson’s untimely death (1877 oil painting by J. G. Fay / National Portrait Galley, public domain)

The Union commanders were simply outmaneuvered and repeatedly surprised by Lee’s smaller but highly mobile Confederate forces. Over the years, he had studied the battles of Napoleon and had learned much from the example of how to wait patiently for the opportune moment to strike with deadly speed. There were losses, to be sure, and stalemates, too. But even late in the war, prior to the Siege of Petersburg and the final surrender, Lee managed to inflict massive damage on the Army of the Potomac in the Overland Campaign of 1864.

Lee was a figure both heroic and tragic in the fullest sense. Profoundly torn by the decision that duty forced him to make, he went into battle against a Union army led by men with whom he had served in Mexico, men he had trusted and admired. Among the young officers serving under those men were many who had been cadets under his command years earlier as superintendent of West Point.

But the full measure of Lee’s tragedy can be understood only in light of the loss at Gettysburg. When the Union’s “Anaconda” strategy began to tighten around Vicksburg in late May of 1863, it became apparent that the loss of that stronghold would give control of the Trans-Mississippi Theater to Union forces. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his war cabinet considered sending massive reinforcements, including two of General James Longstreet’s divisions. Alarmed that such a plan would leave Richmond too vulnerable and result in the loss of Virginia, Lee forcefully argued that Vicksburg would fall long before reinforcements could arrive.

He proposed instead a radical solution: the Army of Northern Virginia must invade the North and threaten Washington, forcing Union troops to withdraw from Virginia to defend the Northern capitol. The plan was bold—and perhaps desperate—though in every major battle against the Army of the Potomac, Lee had emerged victorious. But this time, his army was crippled by the loss of Jackson, and the possibility of success depended largely on the ability of General J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry to keep the movements of the Army of the Potomac under close observation and to keep Lee informed of those movements.

As the main body of Lee’s army moved into Pennsylvania, some 10 days passed without word from Stuart. Lee was marching blind and had no idea that Northern forces—now under the command of General George Meade—had already moved into Pennsylvania behind him and were assembling rapidly to repulse Lee. What little information he did receive came not from Stuart but from one of Longstreet’s spies; but it was too little, too late, and Lee was forced to prepare hastily for battle at Gettysburg.

The story of that loss has been told many times. Some have claimed that the invasion of the North was an act of hubris on Lee’s part; perhaps there was an element of overconfidence. But it is hard to see what choice he had. The alternative was to fight a defensive war in Virginia that had little hope of long-term success against the more powerful and better equipped Northern forces. He had to gamble everything, and it might have worked. However, as the historian and novelist Shelby Foote has written, there was a fatal element of chance in the defeat at Gettysburg:

Fortuity itself, as the deadly game unfolded move by move, appeared to conform to a pattern of hard luck; so much so, indeed, that in time men would say of Lee … that the stars in their courses had fought against him.

In the end, with the better part of his remaining forces surrounded at Petersburg and his supply lines cut off, Lee decided that surrender was the only honorable option left. Some of his advisors argued for a prolongation of the conflict—a guerilla war that would have led to horrific suffering, both for his soldiers and for the civilian population of an already devastated South. Lee rejected that choice. His men, already starving, “would have to plunder & rob to procure subsistence,” Lee argued. “The country would be full of lawless bands in every part, & a state of society would ensue from which it would take the country years to recover.” This final act of his command, an honorable surrender, was his greatest demonstration of forbearance.

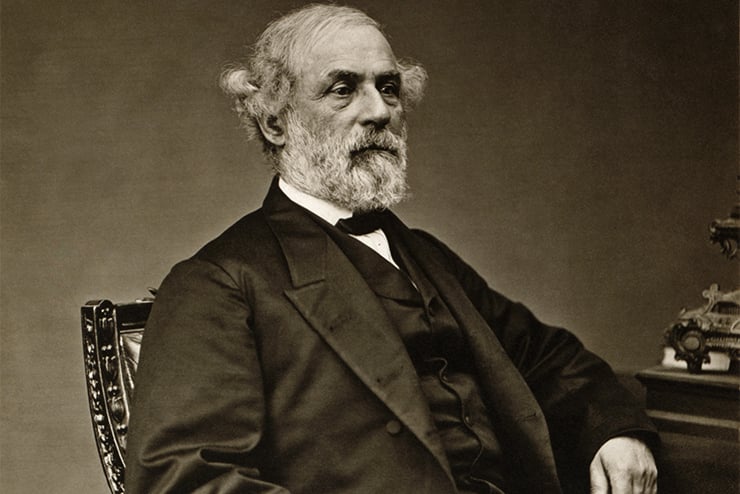

Commander of the Army of Northern Virginia Gen. Robert E. Lee

(National Parks Gallery, Antietam National Battlefield / public domain)

Robert E. Lee’s heroic stature was widely recognized for more than a century after his death. President Dwight D. Eisenhower included a portrait of Lee among those hung in the Oval Office during his tenure. Eisenhower even once said that “a nation of men of Lee’s caliber would be unconquerable in spirit and soul.”

It is shameful today that those who should speak out remain silent while monuments to Lee and other American heroes are toppled. Lee’s reputation is besmirched by those who are true traitors to the American nation. By such dishonorable acts and by our willingness to overlook them, we have become a people unworthy of such heroes.

Top image: Robert E. Lee when he was president of Washington College (Library of Congress).

Leave a Reply