Eugene Genovese was one of the most influential and controversial historians of his generation. Whether Genovese ever self-identified as a conservative remains an intriguing question, without a simple answer. Few people knew him better than I did.

In his teens, Genovese, the son of a Brooklyn dockworker, had joined the Communist Party USA. It eventually expelled him for reasons he never explained publicly, nor privately to close friends. His standard retort to the “Why?” was to say, “I zigged when I was supposed to have zagged.” In 1965, then ex-Vice President Richard Nixon elevated Genovese’s profile by demanding that Rutgers University fire him for statements in support of the Vietcong during a campus teach-in. Genovese left Rutgers, taught briefly in Canada, and then moved back to New York to become chairman of the University of Rochester’s history department. While there, still professing Marxism and atheism, he published Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (1974), a perennial on lists of the 20th century’s most important works of nonfiction.

Two decades later, he formally broke with the left in a penitential j’accuse entitled “The Question,” published in the magazine Dissent in 1994. What did members of the American left know about the horrors of Communism, he asked, and when did they know it? What did they know about its record-setting achievements in “piling up tens of millions of corpses” in the name of social justice? Near the end of his life, he was again praying on bended knee, having returned to the observant Roman Catholic faith of his youth. Facing an end-of-life illness, he turned down the heart surgery that might have prolonged his life.

Genovese devoted his scholarly career to the study of the Old South. His interpretation of Southern history, like his political commitments, reveal both change and continuity. His beloved wife, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, a prominent intellectual in her own right, nuanced and broadened his conceptual thinking about history and political economy. Neither hurrahed three cheers for capitalism; both consistently denounced the descent of the modern world into “moral idiocy” under the spell of radical or possessive individualism; both held fast to a pessimistic view of human nature, acknowledging it as a “Christian insight”; both recoiled at the totalitarian logic of the personal as political. Genovese chuckled whenever anyone in his presence called libertarian thought conservative.

When he wrote Roll, Jordan, Roll, Genovese had acknowledged the influence of the Italian neo-Marxist Antonio Gramsci, who had applied Marxist theory to cultural analysis. By the time he wrote in 2005 The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders’ Worldview, a work of staggering erudition co-authored with his wife and dedicated to a Catholic priest, Gramsci is not even mentioned.

To be sure, Genovese never surrendered the Marxist understanding of the importance of the social relations of production in examining any society. He initially regarded the Old South as “a precapitalist social system” centrally defined by the master-slave relation. Genovese never doubted that Southern slaveholding planters demonstrated profit-consciousness and market-responsiveness. But like Joseph Schumpeter, he rejected those qualities as sufficient in defining the essentials of capitalism. One of the great ironies in the making of the modern world, he argued, was that the demands of consumers in the world’s most advanced economic zones drove the growth of unfree labor markets outside of the capitalist core, which these same advanced societies would come to oppose. Hence England, the greatest beneficiary of the 18th-century Atlantic slave trade, initiated the world’s first anti-slavery crusade.

Genovese’s scholarship contributed significantly to raising the profile of the intelligentsia of the antebellum South, which he argued was superior to Northern scholarship in many fields, like theology, political economy, and history. In The Southern Tradition (1994), a volume derived from his 1993 William E. Massey lecture series at Harvard, he articulated the South’s “achievements and limitations.” Although readily conceding that the Old South’s ruling class was neither homogeneous nor free of contradictions—no ruling class is exempt from such charges—he nonetheless maintained that it exhibited impressive cohesiveness and self-understanding, having evolved within an innovative republican political order. Antebellum Southern intellectuals proved suspicious of abstract reasoning, using reason but never making a cult of it.

Genovese’s view was that antebellum Southern whites justified slavery on the grounds that it was a ubiquitous institution in history, grounded in the Bible, and present before the Flood. Father Abraham served as their model slaveholder. With maturity, in attempting to translate power into authority, Southern Christian slaveholders adopted a moral economy centered on paternalism. They did not deny the role of violence in maintaining the institution, but sought to de-emphasize it in order to elicit the desired behavior from slaves. In the process, however, the consciousness of the slave’s subjective self, his humanity, had to be recognized. The agency of the slaves, as well as of the masters, ultimately defined the nature of the resulting reciprocal, albeit unequal, arrangements. Masters deceived themselves by confusing slaves’ accommodation to enslavement with its acceptance. Slaves were able to qualify the terms of bondage in ways advantageous to themselves, even if it meant eschewing open insurrection—an almost certain death sentence given the gross imbalance of forces. In Roll, Jordan, Roll, Genovese displayed peerless insight into the development of African-American Christianity as a two edged-sword, simultaneously separating slaves from, and binding them to, their masters.

When questioned by a professor after an invited lecture whether he had a problem with the abolitionists, Genovese answered without hesitation, “They were liars.” Of Sicilian heritage, he placed a high value on personal honor and integrity. He made contracts with handshakes. No political movement worth its salt, I heard him once say, could benefit other than from the pursuit of truth. His commitment to high standards in the discipline of history proved unwavering. Such thinking put him at odds with left-wing celebrities like Staughton Lynd and Howard Zinn.

Graduate students often buckled under his demands; he supervised few dissertations to their completion, and showed no favoritism to left-wing students. Still, graduate students from all over the country asked him to read their dissertations and he rarely turned anyone down. His lengthy lists of required seminar readings contained what he regarded as the best and most influential writings regardless of the authors’ politics. Even in his Marxist years, he insisted that the “inevitability of ideological bias does not free us from the responsibility to struggle for maximum objectivity.” For him, respect for the living necessitated respect for and understanding of the dead: “We hold the strange notion that socialists (and all decent human beings) have a duty to contribute through their particular callings to the dignity of human life, a part of which is necessarily the preservation of the record of all human experience.”

Genovese maintained lasting friendships with notable scholars on the left and the right. He and British historian Eric Hobsbawm became lifelong friends. In 1979, he dedicated From Rebellion to Revolution, a remarkable little volume on the history of slave resistance in the Americas, to him. While building the graduate program in history at the University of Rochester in the late 1960s and early 1970s into one of the best in the country, he failed by one vote (cast by Christopher Lasch) to obtain a majority to support the hiring of Paul Gottfried, now editor-in-chief at Chronicles. Two years before his break with the left, he had published The Slaveholders’ Dilemma, a book on the subject of freedom and progress in antebellum Southern conservative thought, dedicated to scholars M. E. Bradford, John Shelton Reed, and Clyde Wilson. In a rousing letter to The New York Review of Books, Genovese defended Bradford during a bitter fight over leadership of the National Endowment for the Humanities under President Ronald Reagan.

According to his New York Times obituary, Genovese once said, “I never gave a damn what people thought of me. And I still don’t.” Well, yes and no. Gene was a complicated man: tough on the outside, soft on the inside. He could be stubborn beyond belief—an immoveable object. Fiercely loyal to his small circle of close friends whose opinions did matter to him, Gene felt betrayal keenly, and the pain tended to make him reclusive. A marvelous host and a great raconteur, he shunned the limelight, drawing a bright shiny line between honor and reputation. Although he was a man possessed of tribal instincts that persistently informed a conservative sensibility, he also had a sense of the transcendent. Unbowed and unbroken by a venal and corrupt academy that ultimately turned its back on him and then savaged him—just as they did his beloved wife Betsey—Genovese bowed out of life with grace. He respected the time and commitments of others. I can still hear him saying, “No fussing; let’s get it over with, then go have a drink.”

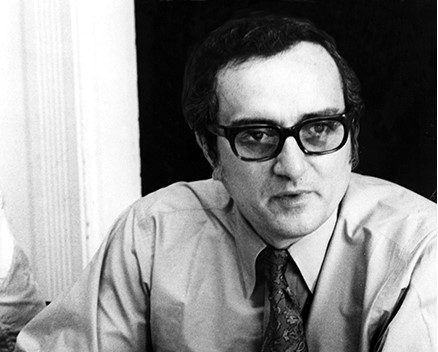

Image Credit: above: Eugene Genovese takes part in the American Historical Association Council meeting in Washington, D.C., on April 7, 1973 (Photo by Charles Del Vecchio/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Leave a Reply