Today, the remarkable life of Capt. Francis Warrington Dawson is little more than a footnote in the history of an era that brought an end in the South to Reconstruction and saw the advent of the “Redeemers” and their Conservative Regime. But in the 1870’s and 80’s, Dawson, founder of the Charleston News and Courier, was a maker of governors and a Confederate hero who dominated the politics of South Carolina for almost two decades before his untimely death in 1889. Born Austin John Reeks in 1840 in London, he was the eldest son of a Catholic family that dated back to the Wars of the Roses. In 1861, he declared his romantic intention to sail for America and join the Confederate struggle for independence, adopting the nom de guerre by which he would be known for the rest of his life.

Three times wounded, Dawson rose to captain’s rank by war’s end. Determined to remain in America, he became a journalist and, by 1867, had acquired an interest in the failing Charleston News. Five years later, Dawson bought out his rival, the Courier, and published the first issue of the combined News and Courier in 1873. During the same period, he married Sarah Morgan, the daughter of a Baton Rouge judge, whose diary of the Civil War years would later make her famous in her own right. By 1876, Dawson had become not merely a Charleston institution but a force to be reckoned with across the state of South Carolina and the South. His politics, like Wade Hampton’s, were conservative in the sense that he favored the restoration of pre-war republican rule by an established elite, but, in other respects, he was a “progressive” who supported a number of “liberal-democratic” causes: women’s suffrage, free trade, low tariffs, civil-service reform, and a prohibition on dueling.

During the years of his dominance of South Carolina politics, Dawson made many political enemies. Ironically, though, it was not a political but a private dispute that resulted in his murder in 1889 at the hands of Dr. Thomas McDow, who became infatuated with the Dawson children’s Swiss governess, Helene Marie Burdayron, by all accounts a remarkably beautiful young woman. According to subsequent trial testimony, on March 12, 1889, the unarmed Dawson confronted McDow at the physician’s residence and, according to McDow, threatened to expose his ungentlemanly conduct in the newspaper. When McDow challenged Dawson’s authority to take such action, Dawson began beating him with a cane. Whereupon, McDow pulled a pistol from his jacket and killed Dawson—as he later claimed—in “self-defense.” In fact, few white men in the South at that time were ever convicted of murder under such circumstances, and the jury at McDow’s trial found the unsavory physician (believed to have been an abortionist) not guilty, in part because the prosecution could not convincingly prove its contention that Dawson had been shot from behind.

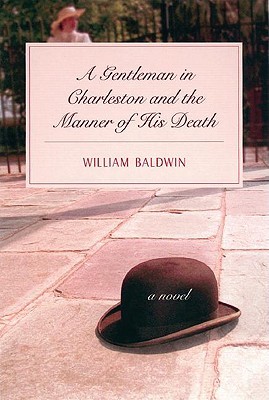

William Baldwin’s latest novel, A Gentleman in Charleston and the Manner of His Death, does not dwell at any length on the forensic drama of McDow’s trial, nor does it delve very deeply into Dawson’s political and journalistic career. Instead, Baldwin fictionalizes the last few years of Dawson’s domestic relations, especially the period after Helene Burdayron’s arrival. What shapes the plot, such as it is, is the portrayal of Dawson’s conflicted interior life: his concerns about his wife’s mental health; his struggle against sexual temptation; his awareness of impending financial and professional calamity; and his premonitions of death. Yet the design of the novel seems at times to work at cross purposes, dissipating the suspense by a sometimes tedious series of digressions filtered primarily through the reflections and memories of the women in Dawson’s life—not only those of his wife and Helene, but, to complicate matters further, of Sarah’s sister, Miriam Dupre.

Dawson’s relations with his wife were certainly troubled. Sarah was a firm believer in the paranormal and was subject to auditory hallucinations—a constant worry for her Catholic husband. Baldwin plausibly introduces into this mix a degree of sexual frustration on Dawson’s part, depicting Sarah as a cerebral and sexually frigid woman. On one occasion, relieved that her husband has gone off to bed without demanding conjugal relations, she reflects:

Such a heaving, such a grunting, such a silliness, and she wondered at God’s wisdom in placing all of humanity in that thoroughly awkward and revealing position—in tying procreation to such an unsettling device.

Yet it would be unfair to suggest that Baldwin has imagined Sarah as an altogether unappealing character. Like the young Sarah Morgan, she is at times capable of a sharp-witted repartee, and the moments of emotional intimacy between her and her husband are convincingly rendered. Drawing upon Sarah’s famous diary (first published in 1913) and her letters, Baldwin ties her mental instability and her obsession with the paranormal to the early death of her brother, Harry Morgan, who was killed in a dueling incident in 1861.

Baldwin’s narrative purpose for bringing Miriam Dupre, Sarah’s sister, into the forefront of the novel is not altogether clear. When the story opens, Miriam is separated from her irresponsible husband, Alcee Dupre, while she and her daughter have become dependent upon Dawson’s generosity. Miriam is beautiful and intelligent, and a palpable erotic attraction between her and her brother-in-law is a central feature of the opening chapters of the novel. Presumably, this contrivance is intended to emphasize both Dawson’s sexual frustration and his self-restraint, even as the reader is teased with the possibility of an eruption of forbidden passion. But Baldwin is not content to allot Miriam a minor role in his tale. Her story continues in the latter chapters when she is resettled in New York, an independent woman who has come to love the anonymity of the great city—so very different from provincial Charleston. She works for a living, supports her daughter, and reflects upon the fate of sister Sarah, tortured by the past and by a repressive social milieu in which the possibilities of violence were always lurking just beneath the surface. “Oh, in the South,” she reflects,

all was deeply felt, and, of course, with love came a commitment to romance and to anger—and to death. . . . In the South weren’t all tainted by this binding passion, this ill-fated direction of their energies?

While Miriam’s reflections provide some useful foreshadowing of the events that will result in Dawson’s death, we are obliged at some length to relive with Miriam the steamy memories of a Gulf Coast honeymoon with her feckless husband, whose sole virtue was his unfailing virility. Lest the reader harbor any doubt, said virility is nicely illustrated in an entirely gratuitous, near-X-rated scene on the beach, which suggests that, should Baldwin apply his talent to the writing of bodice-ripping romances, he would make unseemly gobs of money.

By contrast, given the salacious fictional possibilities inherent in Dawson’s relations with the voluptuous Helene, Baldwin must be congratulated for depicting those relations as essentially chaste, especially since there is no historical evidence to the contrary. From virtually the day of Helene’s arrival, Dawson is captivated by her uncomplicated personality and her naive but potent sexual allure. He dutifully regards himself as her protector in a city full of ravening young rakes but cannot refrain from gazing on her ripe young figure with evident longing. So intense becomes his sexual frustration that he is forced to find relief in frequent visits to Charleston’s many brothels. While Helene is flattered by the gazes of the many men she attracts, she is virtuous enough to want to be married properly. When McDow makes his inevitable advances, she at first resists but is drawn in by his promises to divorce his German wife and marry her. When Dawson confronts McDow, we are encouraged to believe that he is driven not only by a fatherly sense of duty but by repressed passion and sexual possessiveness. Again, this is plausible enough, but, in depicting the scene of violence, Baldwin curiously seems to accept without question McDow’s courtroom testimony, though, in fact, there were no corroborating eyewitnesses.

The central problem that Baldwin has had to grapple with in telling the story of Dawson’s death is that there is simply no conflict between Dawson and his antagonist until, late in the novel, the two fated combatants meet and exchange the only words that have ever passed between them. To compensate for this deficiency, Baldwin introduces, early in the novel, a young man who believes himself to be Dawson’s illegitimate son. David Spenser (a wholly fictitious creation), seethes with hatred for the supposed father who has never acknowledged him. Spenser, too, loves the irresistible Helene; when he is spurned by her, he has even more reason to seek the powerful journalist’s destruction. Though there is a certain implausibility that clings to Spenser’s character, his presence provides a good deal of the suspense that the plot otherwise lacks. Moreover, he is in his way the most intriguing of the characters, and one can easily imagine a very different—possibly better—novel in which his role would be given greater prominence.

Finally, it remains to note that Baldwin has chosen to narrate this tale in a manner that will seem, to some readers at least, a bit too artfully self-conscious. As we learn in the Introduction, the unnamed narrator has been commissioned by the widowed Sarah to create a literary memorial to the great man who has been all but forgotten by the world. This somewhat reluctant narrator is given access to the Dawson letters and diaries and, out of those, creates not a biography but a novel, changing the names of the characters in an obviously transparent fashion. (Dawson becomes “Lawton,” McDow becomes “McCall,” and so on.) All of this awkwardness becomes even more pronounced when we learn that said narrator once lived in Charleston and played a minor but important role in the events leading up to Dawson’s demise. His true identity, however, is concealed until late in the story. Thus we are given a narrator who writes, for the most part, omnisciently, but who, from time to time, slips, with disconcertingly postmodern disregard for narrative continuity, into first-person utterance. However, Baldwin must be congratulated for creating a convincingly detailed portrait of late-19th-century Charleston, one which is populated with personalities whose dialogue is often memorable and witty.

Leave a Reply