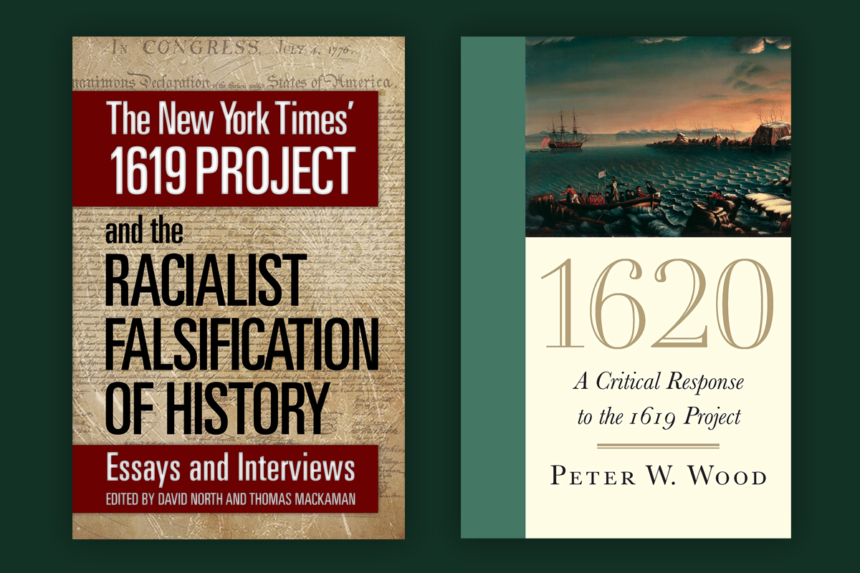

The New York Times’ 1619 Project and the Racialist Falsification of History

by David North and Thomas Mackaman

Mehring Books Inc.

378 pp., $24.95

1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project

by Peter W. Wood

Encounter Books

272 pp., $28.99

Imagine a country in which the major newspaper of its most populous city launches an educational project involving a fundamental reinterpretation—a deliberate misinterpretation, rather—of the moral core of the nation’s history. The nation is envisioned as centrally predicated on racism and enforced racial inequality. The institution of slavery, formally eliminated more than 150 years ago, is seen as the nation’s single most important fact.

Imagine the newspaper understands the country’s founding revolution as a fight to protect slavery from the rising abolitionism of the colonial power that had established it, and that the only reason slavery was eventually undone, against the will of virtually all in the racial majority, is seen as due entirely to the efforts of the racial minority, who made up a mere 15 percent of the country’s population at their emancipation.

This is the dismal road we are on in the age of The New York Times’ 1619 Project. The newspaper’s delusional interpretive effort was quickly recognized by real scholars as pure politics, and these serious people were able to expertly and meticulously annihilate it. Unfortunately, the universities are filled with ideologues masquerading as professors who gave the 1619 Project cover. Cultural elites enthusiastically nodded in sympathy, some because they are true believers in a perverse “down with us” ideology, others because they are terrified of being seen as racists and having their lives and careers demolished. And so the Project achieved wide saturation throughout society and schools, becoming official dogma in short order.

A small bit of consolation for the reader depressed over this situation is two booklength denunciations from scholars on different sides of the political spectrum, a fact which itself goes a long way to showing how empty the 1619 Project truly is. “Vigorously debunked by the Marxian left and the conservative right alike!” is an honest selling point I freely offer to the Times. The Marxian left’s debunking attempt is found in the North and Mackaman book, cited as Racialist Falsification hereafter. Published by Mehring Books, the work contains essays written on the World Socialist Web Site (WSWS), along with interviews of historians. Both Mehring and the WSWS are publishing arms of the International Committee of the Fourth International, an organization of Trotskyist Marxists. Like the racialist 1619 advocates they criticize, the Trotskyists have a motivating prejudice, a one-size-fits-all analytical tool to make sense of the world’s conflict and inequality. Racial Falsification’s critique of radical racialism is directed toward an end—communist revolution. Despite that, any weapon is a good weapon in a street fight.

North and Mackaman present the 1619 Project as a conscious effort to split the working class by aligning poor blacks with black cultural elites. Identity politics of this variety emerged with efforts such as the Combahee River Collective Statement of 1977, which was produced by middle-class black lesbians positing themselves—rather than the poor—as the most oppressed class, and therefore, the engine of revolutionary change. Communist revolution was thus subverted into a campaign for personal advancement and the empowerment of the black intellectual class, rather than for broad economic and social transformation. The end result of the Combahee River Collective Statement is the presence in every major company and institution in the country today of minority diversity trainers and specialists who remind white employees making half what they make of their role in keeping people of color down.

Peter Wood’s book, 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project, joins North and Mackaman in attacking the Project and its advocates for their ahistorical view of American slavery, which was neither unique nor especially brutal in historical relief. The Muslim Barbary pirates took more than a million captured Europeans into slavery in North Africa in a trade that lasted until the 1800s. There were forms of slavery—in some West African kingdoms and in Aztec Mexico—where the level of brutality far exceeded what happened in North America and included offering slaves as human sacrifices. Indentured servitude in early America was experientially similar to slavery, as these servants could be whipped, sold, and separated from family. Some Africans were indentured and subsequently won their freedom, and some became landowners and the owners of slaves themselves.

The Project’s effort to reduce all whites to a single category collapses under scrutiny. The conditions of poor whites in the pre-Civil War South were dismal, sometimes as bad as those of slaves. Poor whites were often the targets of intense repression from elite whites, especially if they were suspected of holding abolitionist beliefs or befriending blacks. They were frequently jailed and lynched for such offenses, and there were poor white riots and insurrections in the South against slavery during the Civil War.

above: Christian prisoners are sold as slaves on a square in Algiers, etching on paper by Jan Luyken, 1684 (Rijksmuseum/public domain)

In Wood’s 1620, which takes its title from the year of the Mayflower Compact, the author describes his perspective as mildly conservative and traditionalist. His understanding of the American experiment is as a noble undertaking of the establishment of a civil body politic based on self-government in which people of conflicting interests pledge to work together to produce a mutually beneficial political order. He deplores polemical exaggeration of the historical import of slavery and racial oppression on both left and right. His evenhanded attempt is admirable, even if in the end he finds precious little to be defended in the Project.

Wood rightly indicates that the scholarly game of historical argumentation—the slow tracing and elaboration of cases by consultation of more and more evidence in the archives—is of no interest whatsoever to the 1619 advocates. Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Project’s leader and self-proclaimed “Beyoncé of journalism,” attains the same level of profundity in her professed craft as the vapid, semi-pornographic pop singer does in the realm of music. Her lead essay has no scholarly apparatus at all—no notes, no bibliography. All its substantive claims, Wood shows, come from two books by the same black nationalist writer, Lerone Bennett, Jr.

above: New York Times journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in 2018 (Alice Vergueiro/Abraji/Wikimedia Commons)

Hannah-Jones also makes numerous egregious errors. For example, she insinuates Lincoln’s racism from his reference to the “troublesome presence” of blacks in the country when he was simply summarizing what Henry Clay believed while eulogizing that Kentucky statesman. Though he humbly acknowledges he is not a Lincoln scholar, Wood notes what easy work it was to “poke around” in relevant literatures and find evidence against her most basic claims, evidence the existence of which Hannah-Jones seems to have had no inkling whatsoever. She comes off poorly in this light, but The New York Times, which, after all, made the abysmally irresponsible decision to give her the platform for steering this effort, looks even worse. What a cataclysmic descent into the muck the “paper of record” has experienced over the last few decades.

Wood deftly takes to task the largely “silent majority of America’s academic historians” who acquiesce in the Project’s premises in meek, obsequious ideological lockstep. The response of woke academia to its scholarly critics amounts to little more than a puerile “noticing” that those critics are mostly white men, and of course we know what that means, don’t we? (Wink wink, nudge nudge.)

The advocates of the Times’ fanciful effort never tire of claiming that slavery is absent in the contemporary historical narrative given to students, when in fact it is already everywhere in high school and college textbooks and teaching. Indeed, this author can even remember being given the entire TV series Roots to watch as part of 7th grade classroom pedagogy way back in the 1970s.

An unavoidable complication of careful analysis, which Wood recognizes, is that many in the reading public are ill-equipped to attend to it. There is unfortunately no helping this. Acute, focused, and rigorous does not often win the day over blustering and bombastic, especially when the latter can command the advantage in media firepower that the 1619 Project can. Their advertising and media campaigns, with glitzy, pop-cultural appeal, rely heavily on the hyperbole, polemics, and assumptions of woke youth culture. With almost no intellectual substance present, the Project will ultimately do the intended work on those too mentally lazy or doctrinally inebriated to ask questions.

The sad state of the schools on this and other weighty matters makes clear that the ground on which these two books fight is only one battlefield in this cultural war. Trustworthy scholars must be consulted, but patriots outside the universities must be heard too, for the schools are nearly entirely swamped by social justice doctrine. The people sitting in faculty offices do not get to decide in their sequestered isolation and self-importance what stories and symbols we should treasure and keep in our collective memory and ritual.

above: Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, colorized version of a photograph by Alexander Gardner, 1863 (public domain)

Regarding Lincoln, there is much interest in both books to muster evidence countering the claim that Lincoln was a crude racist who discounted the humanity of blacks. That blinkered perspective ought to be challenged.

Racialist Falsification approaches, as much as a Marxian text can, Lincoln hagiography by affirmatively invoking Marx’s lofty praise of the 16th U.S. president. 1620 does not make a saint of Lincoln, but rather a canny master politician, whose interest in the repatriation of former slaves to Africa was part of a clever political strategy for assuaging the fears of pro-slavery whites and thereby sparing the Union from civil war.

Is it possible that such seemingly confused sentiment from Lincoln—his adamant anti-slavery position coupled with his early adherence to recolonization—were simply reflective of the true profundity of the dilemma, however imperfectly he might have understood it? The same goes for statements he made indicating skepticism about the coexistence of free whites and free blacks in the same republic.

Multicultural societies are relatively recent inventions with a mediocre track record. Just as an empirical matter, and notwithstanding our moral druthers, there may be real limits as to how viable such societies truly are in the long-term. Of course we have no choice in the United States but to make the best of the situation we are in. An honest appraisal of the chances of achieving a fully integrated and racial conflict-free social order lean at least slightly toward the negative. This is especially true when one of the fields on which opposing cultural sides now fight is that of the very deepest moral nature of the country itself and how it should be taught to the young.

Perhaps Lincoln’s stance on race relations can be better understood through the analysis of arguably the greatest foreign commentator on American democracy in her entire history: Alexis de Tocqueville. He viewed slavery as an affront against nature, but he simultaneously believed abolishing it would not solve the problem of racial animosity in America. Indeed, he was quite blunt on this point, saying, “I do not believe that the white and black races will ever live in any country upon an equal footing.” The only possible solution, in his view, was “mingling” of the two to produce a new race.

But the English, Tocqueville observed, were among the European peoples most ferociously attached to their origins and identity, and American valuation of freedom meant that it was unlikely such a prideful tribe would willingly choose to eliminate itself by intermarrying with members of another in significant numbers.

Tocqueville here footnoted Jefferson—who is, like Lincoln, basely and ignorantly caricatured by the 1619 Project advocates—making the same point. Jefferson predicted the inevitability of emancipation but also the impossibility of “the two races… liv[ing] in a state of equal freedom under the same government.” Much as many would like the second statement to be untrue, the test of its claim is still underway.

I am unaware of whether Hannah-Jones has ever discussed Tocqueville, but I have no doubt that were she to do so, her unsophisticated dogmatism would break him violently apart, forcing him into the same Procrustean mold with which she crushes every other figure in American history. In an early May CNN appearance, she criticized Senator Mitch McConnell’s dismissal of the Project by claiming that McConnell believes “the truth is too difficult for apparently our nation to bear and that we’re far too fragile to be able to withstand the scrutiny of the truth.”

“The truth,” she said, and with a straight face! These two valuable books provide a concentrated demonstration of the vast distance of the 1619 Project from any reasonable definition of that term.

Leave a Reply