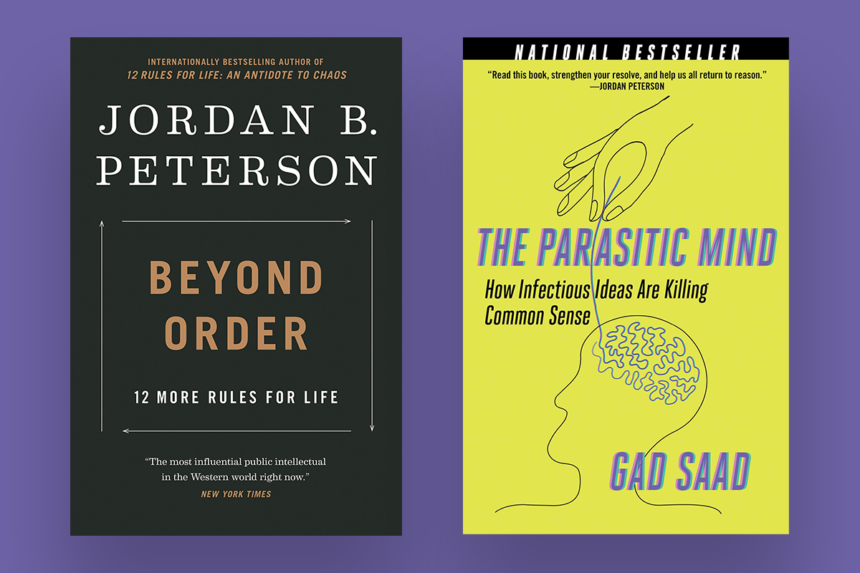

by Jordan B. Peterson

Portfolio

432 pp., Hardcover $29.00

by Gad Saad

Regnery Publishing

235 pp., $28.99

Walmart is for deplorables, the left tells us. If that is so, then Jordan Peterson and Gad Saad must be the deplorables’ favorite academics, for I recently found their latest works amongst the Bibles and redneck reading selections of this revered store.

Unfortunately Peterson and Saad, while rightly critical of today’s deranged political correctness stunts, fail to provide a solid blueprint for conservatives to find their way out of cultural madness. A perusal of their books suggests that their failures lie in their skepticism of religion.

above: microscopic cyst containing Toxoplasma gondii parasites in mouse brain tissue (photo by Jitender P. Dubey, USDA)

Saad’s title is a playful invocation of his scholarly work in evolutionary biology. The study of culture according to the rules of natural selection has interested evolutionary scientists for decades. It is nonetheless a considerable stretch to insinuate that ideas can operate in the minds of those who hold them similar to how parasites hijack other organisms to get them to do their bidding. Perhaps the best known example of this is the single-celled organism Toxoplasma gondii, which invades the brains of rats and alters their behavior to increase the likelihood that they will be devoured by cats, T. gondii’s definitive host. Real parasites are driven to reproduce themselves, but can bad ideas be reasonably understood as operating according to the same logic? The people who hold these bad ideas can endeavor to spread them, but exploring such propagation would require a different book than Saad’s.

In Saad’s argument, Ostrich Parasitic Syndrome is the pathology in which toxic beliefs prevent their holders from seeing elements of reality—e.g., the biological roots of the sex difference—that potentially undermine them. But this is probably true of all ideas, especially political ideologies and religious beliefs. Belief holders will see at least some other beliefs as obviously true and still others as false. This may be unavoidable, for it is simply a feature of how our minds work.

Notwithstanding this central difficulty with his argument, some of Saad’s riffing on evolutionary biological phenomena in order to shed light on leftist cultural politics is clever, and sometimes hilariously funny, such as when he describes skinny, effeminate, male social justice warriors as cuttlefish. Just as the male cuttlefish camouflages as female to achieve covert mating opportunities under the noses of larger, stronger males, so these effeminate social justice warriors adopt feminist attitudes as a sneaky tactic for convincing female allies they would make good boyfriends.

above: illustration of a cuttlefish from The Home and School Reference Work, Volume II, published in 1917 by The Home and School Education Society (public domain)

Hostility to religion—to what Saad brusquely refers to as “the ugliness of tribalism and religious dogma”—is an unwavering aspect of The Parasitic Mind. The autobiographical details Saad provides reveal him experiencing the worst of religious conflict in his native Lebanon as a boy. As a result of that awful experience, he fled what he describes as “the rote prayers and herd-like rituals” of his family’s Jewish faith early in life.

Saad sees wholly unrestricted free inquiry as a core requirement of a rational society. He is confident that full, enthusiastic partisanship for what he calls “Team Reason” would produce a social order superior to any in which religious or cultural norms shaped discussion. David Hume provides the most venerable philosophical response to Saad’s position. Reason is a great, good thing, but it is intimately connected with human emotion, and any ill-informed effort to surgically separate the two can be counted on to produce social and psychological pathologies.

Unlike most rationalist critics of religion, however, Saad has the courage to write troubling truths about Islam, Muslim immigration to the West, anti-Semitism, terrorism, and other topics. He cites analysis of the Islamic holy writings—the Quran, Hadīth, and Sīra—showing that a higher percentage of these texts is given to expressions of anti-Semitism than can be found in Mein Kampf. Even to mention such a fact in a university setting today virtually ensures problems for the speaker, but this does not make it untrue.

Saad enthusiastically advocates the merciless use of parody and sardonic humor as weapons against the machinations of the woke. This is a point of real difference with Peterson, who is at times almost lugubriously serious and solicitous in tone. It is unknown which approach is more likely to change a woke person’s mind, and perhaps neither has much chance of that, provided the infected individual is sufficiently ill with the parasite, to borrow Saad’s terminology.

above left: Jordan B. Peterson, author, clinical psychologist, and professor of psychology at the University of Toronto (Gage Skidmore/ Wikimedia Commons)

above right: Gad Saad, author, evolutionary psychologist, and professor at Concordia University in Montréal (gadsaad.com)

Peterson’s Beyond Order is almost certainly too long and dense for much of its intended audience. It contains occasionally brilliant, insightful life advice, but more often it consists of turgid elaborations of mythologies and archetypes drawn from just about everywhere. Here Pinocchio and Jungian archetypes meet Egyptian gods and dragons, knights, and the characters of J. K. Rowling.

Several of Peterson’s 12 new rules will especially stand out to the conservative reader. The first has to do with the respect due to authority. Rather than the antagonism preached by today’s dreary advocates of critical thinking, which amounts to little more than the arrogant denunciation of all authority, Peterson counsels showing gratitude for the gift of capable and responsible occupiers of high positions in hierarchies.

Stupidly pulling down merited and productive hierarchy in the interest of an abstract, absurd commitment to total equality is no accomplishment. At the university where I teach, a sign just inside the library’s entrance reads, “We are all teachers here.” This is one of the most corrosively wrongheaded messages a student could encounter on a college campus. Effective teachers are a vanishingly rare breed, who have achieved their status through a combination of innate intelligence, long and dedicated training, and the painfully acquired wisdom of experience. Showing up as a freshman qualifies you to learn, not teach.

Conservatives will also appreciate the excellent advice in Beyond Order on marriage, mating, and the meaning of children. Contrary to the dominant message in this culture, one does not find the perfect partner and marriage. One makes a good match by constant effort and the steadfast will to persevere in the relationship. People waiting for perfect matches will find their idealism getting in the way of the practical work on self that is necessary to become the kind of person capable of being married to one other person for a lifetime.

Furthermore, Peterson excoriates the destructive taboo in contemporary American society on telling young people—especially young women—the full truth about having children. Many young women relegate motherhood to the status of a secondary or tertiary interest, sometimes dismissing it altogether, unaware of how their priorities will likely shift later, when it may be too late to act on the change. The reason so many young women look at child-bearing in this way has to do with the culture of careerism and the narcissistic egoism, youth-centrism, and terror of aging and death that accompany it. We should expect that 25-year-olds do not understand themselves or life particularly well, but society’s elders should know better. Yet despite this knowledge these elders continue to teach young people beliefs that will likely come back to haunt them later in life. This is a condemnable cultural crime.

Peterson is not afraid to be an elder sounding this alarm. He can be seen talking with a female reporter about this topic in a YouTube interview I came across while writing this review. As a 38-year-old woman without children, the reporter tells herself she is perfectly happy and pities her female friends with children who seem so much more shackled to the mundane. Peterson dispassionately repeats her age to her and then reminds her that she might well live to 90, making the consequences of today’s choice affect her life for another half century. Has she considered that? Although she initially takes his stance as a personal assault on her own life choices, I discerned a slight alteration in the firmness of her gaze as he finished the phrase. And how could this observation fail to shake her, in a social world that is constantly endeavoring to hide such things from her sight?

Individuals like this young reporter were likely influenced by antinatalist philosophers such as David Benatar, whom Peterson has debated. Benatar is a personable philosopher, but he advances the case that the universe would be a better place without humans, indeed without any sentient life. A universe of only inert matter is better, he argues, because sentient life can suffer, and a universe with suffering is worse than a universe without suffering.

Reading this, I thought of the character Harry Block from Woody Allen’s 1997 film Deconstructing Harry, who recounts how he tried as an infant to preemptively avoid all life’s difficulties by crawling back into his mother’s womb. The idea is humorous in Allen’s context, yet in this one, delivered by the nice professor, who teaches this sinister misanthropic dreck to gullible young people, it is a lesson in the way the perversions of contemporary intellectual culture have permitted the twisting of ethics into abject evil.

Religion and its role in human history and culture are presented in a far more nuanced way in Peterson’s book than in Saad’s Parasitic Mind. But we should not be fooled by the proximity of Beyond Order to the Bible on the shelf at Walmart. Though he cites Judeo-Christian mythology with regularity, Peterson nonetheless maintains a good arm’s length between his own theorizing and the core aspect of monotheistic religious belief, which is the leap of faith.

“The most fundamental stories of the West,” Peterson writes, “are to be found, for better or worse, in the biblical corpus.” But Peterson does not suggest any reason why those stories are so profoundly meaningful for us, nor provide any justification for faith in Scripture or the efficacy of belief in our lives, other than through historical accident.

Peterson discusses “conservative” and “liberal” personality presets. Rather than mere ideologies, they are individual affects of human beings that originate deep in our natures. Some love chaos, change, the new; others prefer order, calm, tradition, and the proven. We need both, he argues.

Maybe so. But what we most desperately need at present, in an age of almost total leftist occupation of the commanding heights of American culture, is a battle plan for how to resist and overthrow all of that.

Saad and Peterson can be picked through for occasional insights on this project. But neither offers the tools for a properly conservative critique of the powers ascendant in America today, or a blueprint with which to replace them. Saad is too convinced of the autonomy of human reason, and though Peterson is more skeptical of that, his emphasis on the ability of myths to move us stops short of recognizing and fortifying what gives them that capacity: their sacredness. Neither author is ultimately on the side of a conservatism that seeks to undo the past century’s revolutionary demolition of America’s polity and society.

Leave a Reply