The U.S. Navy launched a new ship, an oiler christened the USNS Harvey Milk, on Nov. 6, 2021, at Naval Base San Diego, home port of the Pacific Fleet. Younger readers of this magazine may be forgiven if the significance of the name eludes them. Yet it is no exaggeration to say that Harvey Milk is the most celebrated activist in the history of the American gay rights cause.

The American gay rights movement dates from 1950, when the so-called Mattachine Society sought, in the words of Cured, a new PBS documentary, “to assimilate homosexuals into mainstream society and to promote an ‘ethical homosexual culture.’” The commissioning of the USNS Harvey Milk signals just how far that process of assimilation has come, though what an “ethical homosexual culture” might be remains elusive.

In fact, Milk’s career as a gay activist was relatively short-lived. He was already 42 when he “came out” and moved from New York to San Francisco’s Castro District, where he ran a camera shop and began to seek public office as the voice of the district’s burgeoning gay population. After two failed campaigns, he was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. Eleven months later he, along with Mayor George Moscone, was assassinated by a former board member, an ex-cop named Dan White. Among Milk’s fellow Supervisors at the time was Dianne Feinstein, who would become the city’s mayor after Moscone’s death.

White’s motivation for gunning down Moscone and Milk in their city hall offices is usually diagnosed as an extreme case of “homophobia,” though the evidence for this is sketchy. Certainly, it is true that White and Milk were politically at odds: White had been the lone dissenting vote on the Board of Supervisors when San Francisco’s 1978 gay rights bill was passed—a piece of legislation conceived by Milk. The more immediate motivation is that White had been increasingly frustrated by his role on the board and had turned in his resignation just a few weeks prior to the shooting. When his constituents—including much of the police force and a cabal of powerful real estate developers—pressured him to rescind his resignation, the mayor and the board refused his reinstatement. White felt betrayed by Moscone and probably believed that Milk had worked behind the scenes to block his return.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the transformation of Milk’s life and political career into an enabling myth for the gay rights movement was almost instantaneous, despite the fact that Milk’s murder appears to have been a personal vendetta rather than a political act. On the evening following the shootings, a candlelight procession of tens of thousands of gays converged on City Hall, and the word “martyr” rapidly became the most common descriptor of Milk in the days and weeks that followed.

Since then his iconic status has been reaffirmed, not only in San Francisco, but in other cities around the country as well. At the intersection of Castro and Market Streets, a Gay Pride flag flies over Harvey Milk Plaza, and at the San Francisco International Airport, Terminal 1 is today the Harvey Milk Terminal. Streets and schools in New York, Los Angeles, and Portland are named after him. He has been the subject of at least three biographies and an award-winning documentary—all of them in some degree hagiographic representations of their subject.

Most effective, though, in the making of this gay saint, was the 2008 feature film Milk directed by Gus Van Sant and starring Sean Penn. No one disputes that Penn’s performance is extraordinary, yet the ebullient, theatrical, and idealistic hero that he portrays is a confabulation that conceals as much as it reveals. Van Sant’s Milk is the stuff of myth; the real Milk was a smiling opportunist whose serial sexcapades with young men half his age are, in the film, gussied up as the expression of a frustrated quest for domestic bliss. As far as the film is concerned, Milk’s life began, in essence, when he jettisoned his closeted life in New York and traveled west to the city by the Bay, like so many thousands of other gays and lesbians of that era, where there would be no need to lurk “in the shadows” (as the cliché would have it). His prior life is largely ignored, and for good reason.

Milk served in the Navy in the early 1950s as a closeted homosexual, rising to the rank of lieutenant in exemplary fashion. His military career ended in 1955 when he was detained by Navy authorities in San Diego, where he was stationed at the time, for soliciting gay sex partners in that city’s notorious Balboa Park. Interrogated by Navy investigators, Milk admitted to a number of clandestine encounters, describing some of those in rather salacious detail. He was given what is known as an “other than dishonorable” discharge, according to official Navy records.

Milk’s best-known biographer, Randy Shilts, noted in his The Mayor of Castro Street (1982) that Milk had told San Francisco voters that he had been “dishonorably discharged” presumably because the Navy’s judgment against him would be a badge of honor in the eyes of his gay constituency. Yet Lillian Faderman, in her 2018 biography, Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death, wrote that Milk had been “honorably discharged.” Her source was a document on file at the San Francisco Public Library. The library’s archivist, Tim Wilson, stated in a 2020 article in the Bay Area Reporter that he believed the document to have been a forged set of discharge papers. In that same article, Faderman revealed that the perpetrator of the forgery must have been Milk himself.

Apparently, the only civilian who had access to the full Navy report, until last year, was Milk’s gay nephew, Stuart Milk, who oversees the Harvey Milk Foundation. For reasons of his own, Stuart refused to share the report with Faderman. Even today, the Foundation’s official Milk biography merely states that in 1955 “he resigned at the rank of lieutenant junior grade after being officially questioned about his sexual orientation.” One suspects that a full and frank account of Milk’s discharge might discourage healthy fundraising efforts.

It very much appears that Milk, as he cleaned up his act in preparation to run for political office, opportunistically engaged initially in a criminal attempt to falsify his own history. He apparently later thought better of it, but never told the whole truth. But his opportunism didn’t stop there. In his campaigns he had repeatedly stressed the “out of the closet” theme, and prided himself on being the first openly gay candidate for the office of supervisor. He believed that gays who remained in the closet were doing a grave disservice to the gay rights cause.

Among his closest campaign associates was his friend Oliver Sipple, a closeted gay man that Milk had known since his New York days. In September 1975, Sipple happened to be on the scene at Union Square when an assassination attempt was made against then-president Gerald Ford. Sipple intervened and saved Ford’s life. According to a 1989 Los Angeles Times report, Milk, recognizing a golden opportunity to create positive publicity for the cause, “outed” Sipple on the following day with a phone call to the office of Herb Caen, the immensely popular gossip columnist for The San Francisco Chronicle. Although it was well-known by the press that Sipple preferred to keep his orientation private (to protect his family), Caen chose despicably to publish his secret.

Not surprisingly, when the Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro addressed his audience in San Diego on the day that the USNS Harvey Milk was christened, virtually none of this history was mentioned. He suggested that Milk had been the object of discrimination by the Navy and implied that by conferring such an honor on the slain San Francisco supervisor, the Navy had redeemed a grave injustice, while at the same time honoring one of its own who had been a martyr to the civil rights cause.

After Secretary Del Toro’s remarks, the distinction of performing the christening itself was given to Paula M. Neira, a graduate of the Naval Academy who left the Navy in 1991, when she openly declared her transsexuality. Today she is the Program Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender Health. She has worked tirelessly for the normalization of transgender identity in American society, and the U.S. Navy appears to have fully embraced that vision. One wonders whether the good ship Harvey Milk, when it makes port in, say, Dubai, will be flying the rainbow flag bravely beneath the Stars and Stripes.

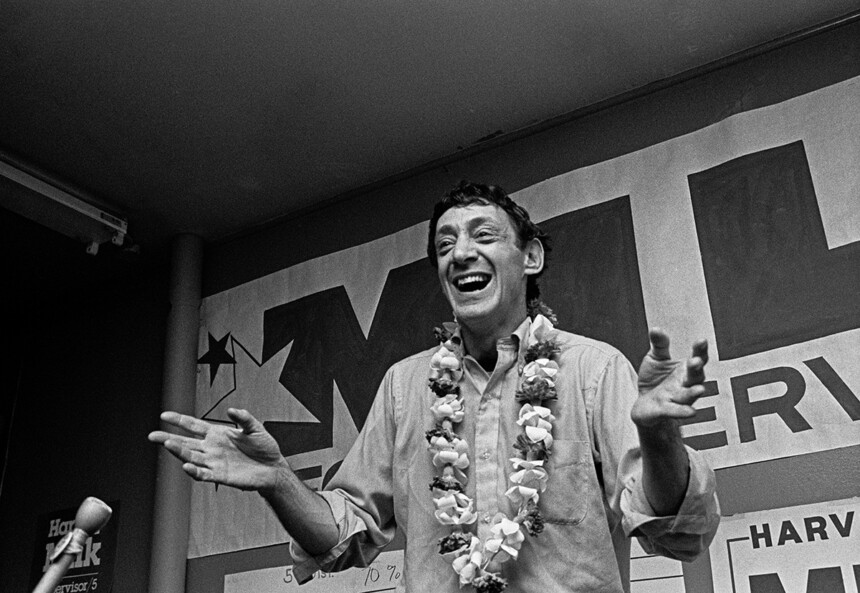

above: Harvey Milk celebrates his election as a San Francisco Supervisor on election night Nov. 8, 1977 (Robert Clay / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply