American politicians love to pretend that they care about the middle class, because they know that the middle class generally determines who gets elected. But once elected, politicians tend to serve those who finance their campaigns, and the interests of large donors seldom align with those of middle-class Americans. This game has been played for a very long time, but there are signs that ordinary Americans are beginning to see through it. In January, Pat Caddell released a poll of those who had voted Republican in November’s midterm elections. When Caddell asked, “Is John Boehner for average Americans at heart rather than for special interests?” only 44 percent of these Republican voters said that Boehner favored average Americans, while 43 percent said he favored special interests. Similarly, as noted by Rick Newman of Yahoo Finance on January 16, Barack Obama’s lowest level of support is among Americans earning between $5,000 and $7,499 per month.

Newman’s article also explored some of the sources of middle-class dissatisfaction. College costs have gone up 5.2 percent per year during Obama’s presidency, while student debt jumped 58 percent. The cost of medical care has increased five percent per year during Obama’s tenure. These soaring costs have accompanied stagnating wages. As the Washington Post noted in a series on “Why America’s middle class is lost” in December, the middle class encompassed 59 percent of Americans in 1981 but only 51 percent in 2011, and its share of the national income fell from 60 to 45 percent during the same period. The Post also reported that two-parent families earned 23 percent more than they did in 1973, after adjusting for inflation, but only because such families were working 26 percent more hours. The middle class is shrinking, and its income is stagnating, because massive numbers of jobs were lost in the last three recessions, especially, as the Post notes, those “jobs that companies could easily outsource overseas or replace with a machine”; 5.5 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since 1990, and at least 2 million jobs have been lost because of imports from China alone.

Then there is the cause of wage compression that the Post chose to ignore. Prof. George Borjas of Harvard has estimated that mass immigration results in a net wage loss of $402 billion annually for American workers, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics has found that all net employment gains since the recession have gone to foreign-born workers. Compared with workers at the start of the most recent recession, 1.5 million fewer American-born workers hold jobs today, even though the number of adults born in the United States increased by 11 million over the same period.

Even though Barack Obama spent his State of the Union Address warbling about “middle-class economics,” he did nothing to address these causes of middle-class dispossession. Instead, he has committed himself to more mass immigration and more job-killing trade deals. After the midterm elections, Obama announced an executive amnesty for five to six million illegal immigrants. He fully supported the immigration bill that passed the Senate before stalling in the House. That bill would have tripled the number of permanent-residence permits and doubled foreign guest-worker admissions over the next ten years. And in the State of the Union Address, Obama asked for “trade promotion authority,” a reference to the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, two trade deals cut from the same cloth as NAFTA.

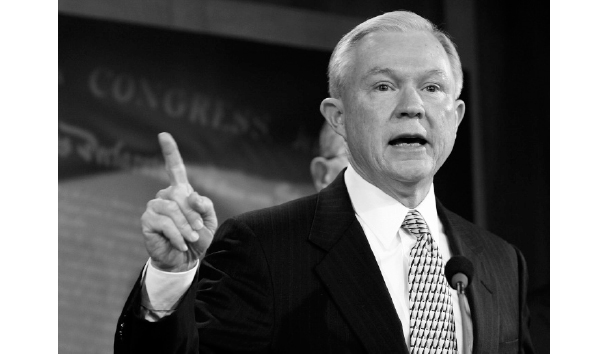

Obama’s support for mass immigration and free trade represents an enormous opportunity for Republicans, if they can bring themselves to grasp it. A cogent plan for seizing this opportunity is laid out in Alabama Republican Sen. Jeff Sessions’ “Immigration Handbook for the New Republican Majority” (my source for Professor Borjas’s statistics on immigration and wage compression), issued before the GOP retreat in January.

As Sessions notes at the outset,

The principal economic dilemma of our time is the very large number of people who either are not working at all, or [are] not earning a wage great enough to be financially independent. The surplus of available labor is compounded by the loss of manufacturing jobs due to global competition and reduced demand for workers due to automation.

This economic dilemma is only exacerbated by mass immigration, and Sessions spends most of the 23 pages of his handbook puncturing all the arguments made for mass immigration and explaining why Republicans would benefit politically from opposing not just Obama’s executive amnesty but mass immigration in general. The evidence Sessions presents is impressive, and his conclusions are clear:

Republicans . . . must define themselves as the party of the American worker, the party of higher wages, and the one party that defends the American people from Democrats’ extreme agenda of open borders and economic stagnation.

As Sessions notes, the issues involved are fundamental:

Is America a sovereign nation that has the right to control its borders and decide who comes to live and work here? Should American immigration laws serve the just interest of the country and its citizens? And do those citizens have the right to expect and demand that the laws passed by their elected representatives be enforced?

If Republicans wish to win the battle for the middle class, they will listen to Jeff Sessions.

Leave a Reply