If you think the removal of the Confederate Battle Flag from the grounds of the South Carolina capitol was the end of flag controversy, you may be surprised to learn that an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times declared, “It’s time California dump” the Bear Flag, “a symbol of blatant illegality and racial prejudice. Like the Confederate cross of St. Andrew, the Bear Flag is a symbol whose time has come and gone.” A Californian born and reared, I’m beginning to understand how Southerners must be feeling as their heritage is being erased. The op-ed also calls the Bear Flaggers “a band of thieves, drunks and murderers.” Such a characterization of the Bear Flaggers is propaganda, not history.

A look at the men who raised the Bear Flag over the California Republic on June 14, 1846, in Sonoma reveals character, substance, and courage. William Ide, who acted as “Commander” of the Bear Flaggers and was elected president of the newly proclaimed republic, was born in Massachusetts but spent many of his early years in Vermont. He received a good education and would later study law. After working a variety of jobs, he moved west—first to Ohio, then Missouri, and then Illinois. While in Ohio, he joined the Latter-Day Saints. He was especially attracted to the Mormon emphasis on total abstinence, frugality, and hard work. He soon became disaffected for several reasons, particularly Joseph Smith’s advocacy of polygyny. Ide broke with the Mormons for good when he left Illinois for California in 1845.

Ide piled his wife, Sarah, and their six children—three other children had died earlier—and all the family’s worldly belongings into three covered wagons and joined what became known as the Grigsby-Ide party on a six-month trek to California. Ide was elected “hayward,” putting him in charge of watering, feeding, and protecting the cattle of the many families in the wagon train from Indian attacks. Later in the journey, Ide used his engineering skills to get all the party’s wagons through the Sierras intact, something achieved by only one other party at the time. Once in California, Ide settled his family on a ranch owned by an American, who allowed Ide to build a log cabin on the property in return for work. In addition to all the typical labor on the ranch, Ide employed another of his skills and surveyed the property.

After the American conquest of California, Ide surveyed several ranches, including the ranch of Thomas Larkin, who had served as U.S. consul at Monterey during California’s Mexican period. In June 1847, the military governor of California, Col. Richard Mason, appointed Ide the Northern Department surveyor. In addition to surveying, he worked hard developing his own ranch in Colusa County. He became the county’s justice of the peace, then deputy county clerk, then treasurer. He would also serve as county judge before he died of smallpox in December 1852. A monument was erected in his honor.

Another leading Bear Flagger was John Grigsby. Born and reared in Tennessee, he became a farmer and a trader in Missouri. He served as captain of the Grigsby-Ide party on the 1,800-mile trek to California. Accompanying him were his wife and seven children. Like Ide, Grigsby found work on the ranch of an American. In Grigsby’s case this meant George Yount’s spread in the Napa Valley. After serving with the Bear Flaggers and as captain of E Company with John C. Fremont and the California Battalion, Grigsby bought property in the Napa Valley and dedicated himself to growing wheat and grazing cattle. During the 1850’s he was involved in building roads, bridges, and mills. He was well respected as one of the pioneers of the valley. He died in 1876 while visiting relatives in Missouri.

Regarded as an equal to Ide and Grigsby among the Bear Flaggers was Kentucky-born Robert Semple. He was the son of a Kentucky legislator who trained him in law and dentistry, but he spent his young-adult years as a steamboat captain on the Mississippi. Mary Todd Lincoln’s sister knew Semple and described him as “the most brilliant man” she had ever met. Semple left for California in August 1844. An August departure was flirting with disaster. Wagon trains left in April or May, as soon as the grass was up on the plains, but Semple was a member of a party of ten men, who were making the journey on horseback with pack mules. An overenthusiastic California booster, Landsford Hastings, convinced the others that they could do it before snows closed the Sierras.

Hastings was right, though just barely, and the party arrived at Sutter’s Fort on Christmas Day, exhausted and hungry. Standing 6’8″, Semple looked skeletal, and his buckskin outfit was torn and patched and sewn. A British naval officer whose ship lay anchored at Monterey happened to be at Sutter’s Fort. He struck up a conversation with Semple and came away saying that Semple knew more of British history than he did. Sutter was also impressed by Semple and hired him on the spot. When the Bears were organized, Semple took a leading role and at Sonoma was elected secretary. He was one of those who negotiated surrender terms with General Vallejo and later served with the California Battalion.

When hostilities ceased, Semple and a partner founded California’s first daily newspaper, the Alta California. On July 4, 1849, Semple began printing the paper using a steam press, the first in the West. Semple was the first to call for a California constitutional convention, and when one was convened in 1850 he was elected president. He attended most meetings on a litter after a recurrence of malaria. Nonetheless, he was a strong leader, an eloquent speaker, and a political sage. Although he ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in 1852, he was highly respected, and it looked as if he had a long political career ahead of him. However, in 1854 he was thrown when breaking a horse on his ranch and died from the injuries.

One of the few Bears not born in the United States was Patrick McChristian. Born in Ireland in 1796, he immigrated to America at the age of 15. Early in 1825 he was married in New York, and by the end of the year the first of his eight children was born. McChristian moved the growing family ever westward, first to Ohio, then Missouri, and in 1845, as part of the 45-wagon Grigsby-Ide party, to California. An experienced blacksmith, miller, and farmer, McChristian had no problem locating work. He soon found himself on the ranch of George Yount, where he fashioned a plow of his own design that was much sought after.

McChristian was one of the early Bears, and his two oldest sons, Pat Jr. and James, although still teenagers, would also serve with the Bears and later with Fremont’s California Battalion. The entire McChristian family was at Sonoma on June 14, 1846, to watch the raising of the Bear Flag, and Pat Jr., James, and William helped hoist it. After the war, McChristian bought 430 acres of property in the Sonoma Valley from his son-in-law Jasper O’Farrell, who had married Mary Ann McChristian in 1846. A Dublin-educated civil engineer, O’Farrell arrived in California by sea in 1843 and surveyed lands for Pío Pico in Southern California and what would become Marin and Sonoma counties in northern California for the Mexican government. He would later survey the site and lay out the streets for the future city of San Francisco.

McChristian grazed cattle and grew wheat on his Sonoma property but also planted dozens of acres of fruit trees, making him a pioneer in the latter endeavor. Pat Jr. carried on the tradition, especially with apple trees. The McChristians were largely responsible for making the area around Sebastopol the “Gravenstein Apple Capital of the World.” It’s unclear when McChristian died, but several sources say that it was in 1852 while he was on a trip by sea to the East Coast to visit relatives. Pat Jr. died in 1888, but several of the McChristian children lived into the 20th century. James McChristian died in 1914, the last of the Bear Flaggers.

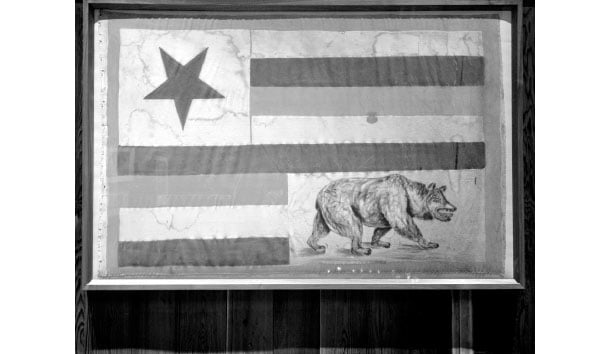

Found stored among the effects of Patrick McChristian was a Bear Flag. It is the only known Bear Flag that was the property of one of the Bears. It is made of quality cloth and carefully stitched. It features a bear and a single star that is common to the California state flag today, but the McChristian bear is portrayed in an aggressive pacing motion with teeth bared. The flag also has several red, white, and blue stripes. The flag is in a private collection but is on display in the visitor’s center at Schramsberg Vineyards in California’s Napa Valley.

William Ide, John Grigsby, Robert Semple, Patrick McChristian, and the other Bear Flaggers were anything but “thieves, drunks, and murderers,” although the effort is on to erase them and the Bear Flag from California’s history.

Leave a Reply