While nearly all my college students had heard of Lexington and Concord and the first battle of our Revolutionary War, only rarely did any of them know why the British were marching on the small Massachusetts towns.

During the summer of 1774, Gen. Thomas Gage, supported by a squadron of the Royal Navy and five regiments of soldiers, was appointed governor and captain-general of Massachusetts, and the Massachusetts legislature was dissolved.

But Americans were ornery and independent back then, and resistance was immediate and widespread. The colonists even elected another legislature, which was declared illegal by Gage. Nonetheless, the legislature, led by John Hancock and Sam Adams, met in Concord and openly defied the British general. By October, Massachusetts, outside of Boston, was virtually independent.

Through the fall and winter and into the spring of 1775, the rebel government in Concord collected arms and ammunition, and throughout Massachusetts militia drilled. Most militiamen were farmers, but there were also hunters and trappers, craftsmen, mechanics, teamsters, sailors, and shopkeepers.

Early in April 1775, Gage dispatched several spies to gather intelligence, including Ensign Henry DeBerniere and Sergeant John Howe. Howe’s “Journal” was published in Massachusetts a half-century after his spying mission, and some have argued that it is really a record of DeBerniere’s spying. In the journal, Howe describes an encounter he had with an elderly man and his wife at their house on a road leading from the backcountry into Boston. The man was sitting on his porch, cleaning his rifle.

“I asked him,” Howe reported to Gage,

what he was going to kill, as he was so old, I should not think he could take sight at any game. He said there was a flock of redcoats at Boston, which he expected would be here soon, he meant to try and hit some of them, as he expected they would be very good marks. . . .

I asked the old man how he expected to fight. He said, open field fighting, or any other way to kill them red-coats. I asked him how old he was. He said seventy-seven, and never was killed yet. . . . I asked the old man if there were any tories [sic] nigh there. He said there was one tory house in sight, and he wished it was in flames. . . . The old man says, Old woman put in the bullet pouch a handful of buckshot, as I understood the English like an assortment of plums.

This and other such reports from his spies inspired Gage to act. He issued orders to march on Concord, capture the rebel leaders, and, most importantly, confiscate all arms and ammunition. The bloody colonists must be disarmed! By the time that nearly 800 British troops, under Lt. Col. Francis Smith, were on the road to Concord, Americans all along the route had been alerted by Paul Revere, Will Dawes, and Sam Prescott.

When the British reached Lexington, they found militia captain John Parker and 70 of his Minutemen— so named because they must be ready with rifle and shot in one minute—assembled on the village green. In the van of the British advance was Maj. John Pitcairn and his 400 light infantrymen, their scarlet coats and white breeches, and muskets and bayonets, catching the first rays of the rising sun. In the face of this impressive sight, Captain Parker ordered his Minutemen, “Stand your ground, boys. Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.”

Major Pitcairn and three other British officers rode to within a hundred feet of the assembled militiamen and shouted, “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels, and disperse.” Parker looked at Pitcairn’s overwhelming numbers and decided a pitched battle would be suicidal. He ordered his men to fall out. They did so, but not one man would surrender his rifle. “Damn you!” shouted Pitcairn. “Why don’t you lay down your arms?” Another British officer shouted, “Damn them! We will have them!”

A shot rang out. American militiamen said a British officer fired. The British claimed an American fired. What is known for certain is that hundreds of British guns belched smoke, eight Americans were killed, and ten more wounded. The British then hurried on to Concord, encountering no opposition along the way but hearing guns fired and bells rung in the distance, signals that militiamen were being called to duty. By the time the British reached Concord, hundreds of Minutemen in small scattered groups were there to meet them.

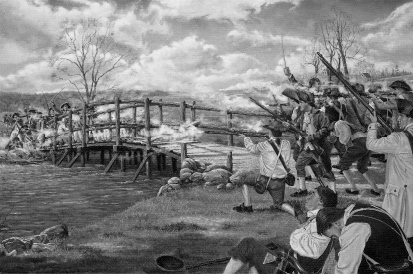

At Old North Bridge, the British troops opened fire on Minutemen, killing two and wounding four, but the Minuteman returned fire and advanced, killing and wounding 15 British officers and men. Outmaneuvered and stunned by the accuracy of the Minutemen’s fire, the British abandoned their wounded and fled. Fleeing British soldiers collided with reinforcements trying to move to the front. It was some time before Lieutenant Colonel Smith could reorganize his forces. Even then Minutemen sharpshooters continued to drop British troops wherever they were. By early afternoon Smith had begun a retreat to Boston.

You know the rest. In the books you have read

How the British Regulars fired and fled,—

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And pausing only to fire and load.

At Meriam’s Corner, Brooks Hill, Brooks Tavern, the Bloody Curve, Hartwell’s Farm, Parker’s Revenge, the Bluff, Fiske Hill, and Concord Hill, Minutemen hit Smith’s retreating column again and again. Smith sent out troops to protect his flanks, but the redcoats were ambushed by sharpshooting farmers. Two British ammunition wagons that had become separated from the main column were stopped by a special auxiliary force of Minutemen, deemed too old to be part of the regular militia. The men were all more than 60, and many in their 70’s. When they demanded the surrender of the wagons, the British officer in charge ordered his 13 soldiers to ignore the old fools and proceed. The graybeards opened fire, shooting the lead horses, wounding the officer, and killing two sergeants. The other British soldiers took off running, dropping their weapons for greater speed.

By the time the British reached Boston, they had suffered 300 casualties.

“The rebels,” said British Brig. Gen. Hugh Percy, who led reinforcements to aid Smith, “attacked us in a very scattered, irregular manner, but with perseverance and resolution . . . ” Percy understood that he was not facing a regular army but something far more dangerous: well-armed Americans fighting to protect hearth and home, and their liberty.

Leave a Reply