A tale of two presidents on war and peace.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

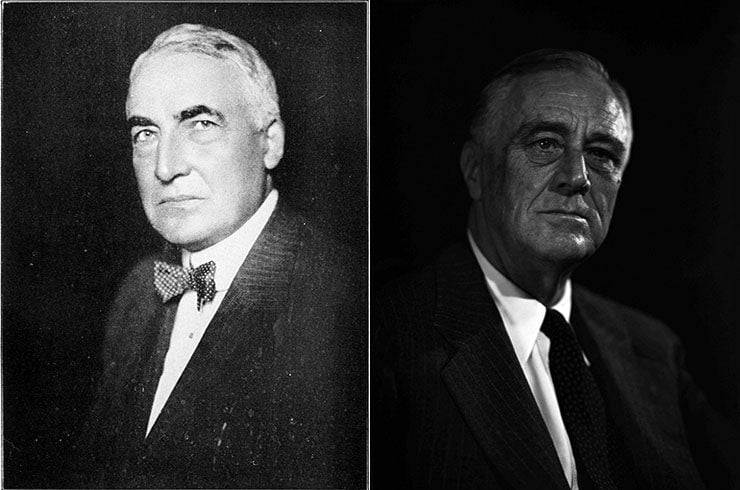

So said Charles Dickens in his famous 1859 novel, A Tale of Two Cities. But his description could have easily defined two American presidents and their respective policies on foreign affairs in the 1920s and 1930s. Perhaps no two presidents were as diametrically opposed on nearly every policy issue as Warren G. Harding and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Scholars and historians, as if to further emphasize the distance between the two men, always rank FDR as one of America’s greatest chief executives, while Harding is always placed near the bottom. For example, in the International Relations category of C-SPAN’s 2021 presidential ranking, Roosevelt finished at the top of the list; Harding was at number 34. This (mis)perception is one of the great tragedies in all of historical scholarship.

Warren Gamaliel Harding came into office in 1921, inheriting a foreign policy that was in shambles, a gift from his progressive predecessor, Woodrow Wilson, who had involved the U.S. in the Great War and poisoned relations with many nations, including Mexico and other countries in Latin America. The change in administrations pleased many, including the president of Mexico, Álvaro Obregón, who described Harding’s inauguration as “a day of deliverance” from the heavy-handedness of Wilson. American foreign policy was about to undergo a complete transformation.

In just 882 days in office, Harding and his administration negotiated a formal agreement to end the Great War in Europe, bring home U.S. troops from the Rhineland in Germany and from parts of the Caribbean, improve relations with Mexico and Latin America, initiate and exhort the World War Foreign Debt Commission to find a solution to the mounting problem of crippling war debt, send food to starving millions in Russia, and call the first disarmament conference for the purpose of reducing the world’s most dangerous weapons. Yet these achievements are lost in what is labeled a failed presidency by the so-called experts.

The first issue Harding had to deal with was the aftermath of World War I. While serving in the Senate in 1917, Harding voted to declare war on Germany. But once the carnage was over, like most Americans, he wanted no more of war and sought instead a return to a less interventionist American foreign policy. He saw that the League of Nations was not the way to accomplish that. As a member of the Foreign Relations Committee, then-Senator Harding helped to prevent U.S. membership in the new international body.

He carried that theme over to his presidential campaign in 1920. On the stump, he said these memorable words:

I think it’s an inspiration to patriotic devotion to safeguard America first, to stabilize America first, to prosper America first, to think of America first, to exalt America first, to live for and revere America first.

And in his inaugural address in 1921, he did not back away from his belief in a more traditional foreign policy.

The recorded progress of our Republic, materially and spiritually, in itself proves the wisdom of the inherited policy of noninvolvement in Old World affairs. Confident of our ability to work out our own destiny, and jealously guarding our right to do so, we seek no part in directing the destinies of the Old World. We do not mean to be entangled. We will accept no responsibility except as our own conscience and judgment, in each instance, may determine.

Within a few months of taking office, Harding traveled to Hoboken, New Jersey to speak at a solemn occasion. On the docks, arriving from France on that day, were 5,212 wooden caskets holding the remains of American servicemen. “I find a hundred thousand sorrows touching my heart, and there is a ringing in my ears, like an admonition eternal, an insistent call, ‘It must not be again! It must not be again!’” said the tearful president.

To help work toward a world without the threat of war hanging over it, Harding called the Washington Disarmament Conference, also known as the Washington Naval Conference. (In those days, naval forces were seen as harboring the world’s worst weapons, which perception was at least partially to blame for the Great War, as Britain and Germany raced to build the most lethal fleet.)

Even Sir Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty during World War I, approved of the meeting. “I have high hopes of this Washington Conference,” he said. “It has been called together by President Harding in a spirit of the utmost sincerity and good will.” Harding had high hopes as well. He desired the “peace of the world, the proximate end of the frightful waste of competing armaments, and the establishment of peace on earth, good-will toward men.” The conference, though, was not the call of the United States alone, he said, but “the spoken word of a war-wearied world, struggling for restoration, hungering and thirsting for better relationship; of humanity crying for relief and craving assurances of lasting peace.”

“I think it’s an inspiration to patriotic devotion to safeguard America first, to stabilize America first, to prosper America first, to think of America first, to exalt America first, to live for and revere America first.”

Warren G. Harding

The nations of the world, said Harding, “demand liberty and justice. There cannot be one without the other … Inherent rights are of God, and the tragedies of the world originate in their attempted denial.” And such a denial is put into play by machines of war. People everywhere “who pay in peace and die in war wish their statesmen to turn the expenditures for destruction into means of construction, aimed at a higher state for those who live and follow after.” That was the purpose of the conference: to be a lasting “service to mankind.”

And it was a smashing success. It accomplished its main goal of instituting limits on naval armaments, but it also banned the use of poison gas on the battlefield and, in separate meetings by the great powers in the world, produced several treaties aimed at the easing of tensions in Asia. Harding had hoped this objective could be attained, as he wrote to the governor of the Hawaii Territory: “The Pacific ought to be the seat of a generous, free, open-minded competition between the aspirations and endeavors of the oldest and newest forms of human society.”

Though Harding gets very little credit for the conference, one of America’s preeminent diplomatic historians, Thomas Bailey, wrote that this conference was the only international meeting of the 1920s and 1930s “to achieve really significant results” and that it “may have averted war in the Pacific for a decade.” As Pat Buchanan has put it,

[Harding] negotiated the greatest disarmament treaty of the century, the Washington Naval Agreement, which gave the United States superiority in battleships and left us and Great Britain with capital-ship strength more than three times as great as Japan’s. Even Tokyo conceded a U.S. diplomatic victory.

In his unprecedented 4,422 days in the presidential chair, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s attitude about diplomacy was far different than that of Warren Harding. During his campaign in 1920, Harding was adamant that the people know exactly what his political positions were, once remarking, “Let them (the people) know it all, and then let them decide. Don’t let’s cheat ’em; let’s make the record full and fair. We mustn’t cheat ‘em.” Harding was true to his word. By contrast, Roosevelt was a deceiver. “You know I am a juggler, and I never let my right hand know what my left hand does,” FDR told a friend. “I am perfectly willing to mislead and tell untruths if it will help win the war.”

Roosevelt had brandished his supposed anti-war credentials as early as his first term. “I have seen war. I hate war,” he said in a public speech in 1936, as he was moving toward re-election. And two days after Hitler’s invasion of Poland, on September 3, 1939 he stated to the American public,

This nation will remain a neutral nation … I have said not once but many times that I have seen war and that I hate war. I say that again and again. I hope the United States will keep out of this war. I believe that it will. And I give you assurances that every effort of your Government will be directed toward that end. As long as it remains within my power to prevent, there will be no blackout of peace in the United States.

In October 1940, in the midst of his quest for an unprecedented third term, FDR gave a solemn pledge in Boston:

And while I am talking to you mothers and fathers, I give you one more assurance. I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.

At the beginning of the war in Europe, 90 percent of the American people wanted to stay out of it, and Congress had passed a number of neutrality acts. Yet FDR was quietly angling to get into the action, especially in the fight against Hitler. A Pan-American Security Zone was declared, and U.S. Navy ships escorted merchant

convoys within the zone, since the neutral U.S. began selling armaments to belligerents on a cash-and-carry basis. FDR eventually moved the line to within 50 miles of Iceland.

On Sep. 4, 1941, FDR addressed the nation in one of his Fireside Chats to report that the USS Greer, sailing innocently toward Greenland to ferry mail to troops there, was attacked by a German submarine. What the president failed to mention was that the Greer was not actually innocent in the incident but had been shadowing the U-boat and was assisting a British plane in an attempt to sink the sub. Roosevelt had already issued classified orders to the Navy to begin escorting British ships in the Atlantic.

Of this arrangement, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was well aware. He reported to the War Cabinet in August:

The President had said he would wage war but not declare it and that he would become more and more provocative. If the Germans did not like it they could attack American forces… The President’s orders to these [United States Navy] escorts were to attack any [German] U‐boat which showed itself, even if it were 200 or 300 miles away from the convoy. Everything was to be done to force an incident.

Three months later, on Dec. 4, 1941, and three days before Pearl Harbor, the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Times-Herald published secret war plans, known as “Rainbow 5,” which called for raising a 10-million-man army and deploying 5 million troops to Europe in 1943 to defeat Hitler. FDR had ordered the plans drawn up and approved them once they were completed. Despite the leak, later in December Congress approved an appropriation of over $25 billion to increase military forces, pushing the army up to 2 million soldiers.

On the other side of the globe, during the same period, the Roosevelt administration was waging economic warfare against Japan, which had to import about 90 percent of its vital military necessities, like oil and scrap metal, and which had been supplied primarily by the United States. Though FDR had declared the U.S. a “neutral nation,” he imposed severe sanctions on Japan, freezing assets and pronouncing an embargo in the summer of 1941. This had the effect of backing the Japanese into a corner.

Rather than try to normalize relations, Roosevelt increased the tension, leading to an inevitable result. Secretary of War Henry Stimson recorded the following in his diary entry of Nov. 25, 1941:

[FDR] brought up the event that we were likely to be attacked perhaps next Monday [December 1], for the Japanese are notorious for making an attack without warning, and the question was what we should do. The question was how we should maneuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.

But there was danger, leading to the most horrific war in the history of the world, costing the lives of more than 80 million people, most of whom were civilians.

Warren Harding sought a peaceful world and was accordingly twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize; FDR deceived the nation into total war, extending even to attacks on civilian populations, including the use of napalm and white phosphorous in bombing raids on Japanese and German cities. The respective records of the two presidents on war and peace are light-years apart.

Top image: Warren G. Harding in 1921 (Underwood & Underwood / Public domain) and Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1944 (FDR Presidential Library & Museum / CC BY 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply