Because Héctor had experience as an historical researcher looking up books on the subject of Pancho Villa at the public library, it was agreed that he should be the one responsible for ascertaining the location of the treasure, and that the job of Jesús “Eddie” would be to outfit the expedition to Ladron Peak when the time arrived to set forth upon their quest.

To his chagrin, Héctor discovered that historical detective work required a good deal more knowledge and expertise than checking out books from the library did. At a loss as to where to begin, he settled finally on the Valencia County News-Bulletin. Having printed the story, Héctor reasoned, the paper’s editor must be well versed in the events it described. In fact the editor was too busy to see him, and the receptionist referred Héctor to an editorial assistant who said she worked part-time for the newspaper while taking classes at the University of New Mexico Valencia Campus. The treasure story, she explained, had appeared in what was known to the trade as a “canned” article, meaning that no one at the News-Bulletin knew anything whatsoever about the subject matter. If Héctor needed further information, she suggested he visit the Harvey House Museum at 712 Dalies Street and ask to speak with the column’s author.

Héctor had heard of the museum, but only as the custodian of a miniature-train collection. He drove there at once and was told by a docent that the address of the Historical Society was 104 North First. Irked, he got back in the van and drove on to First Street. Historical research, Héctor decided, was a lot more tedious than he’d realized. Perhaps, after all, he should have started with the internet, which meant a saving in physical effort at least, as well as in gas. When he found the Society closed and no one about to answer the bell, he decided it was the last straw and went straight home. Computers were his business, and if he couldn’t find what he was looking for on the web, chances were the thing didn’t exist, or never had in the first place. In the easeful privacy of his office, Héctor seated himself before the glowing screen and typed camino real apache raid stolen treasure ladron peak into the search engine and hit return. He was still at it three hours later when AveMaría got home from the supermarket after picking up Contracepción at Darfur Relief. Nothing. Zilch. Nada.

That evening at the Taberna Aztlán, Héctor recounted the events—or nonevents—of his discouraging day to Jesús “Eddie.” His friend was sympathetic, but not particularly helpful otherwise. History was bullsh-t, he asserted. His Grandfather Luis would have been able to tell Héctor everything he needed to know about the Camino Real legend. Unfortunately, Grandfather Luis was dead. Hence there was nothing Héctor could do but consult a curandera if they were to lay hands on the Spanish treasure.

“I thought curanderas healed people,” Héctor told him, doubtfully.

“Hombre, they do. But they are also a kind of bruja. The best ones can see everything, they can foretell the future—and the past! There are not many left anymore—most are in Mexico. But Beatriz knows one, right here in town. She is very old, compadre—maybe a hundred years or more! Also she is a padrone at Our Lady of Belen. Only, the priest does not know this. He would excommunicate her if he found out about it, Beatriz says. She’s got mad and threatened to tell him—many times—but in the end she has always chickened out.”

The thought of consulting such a woman, or even being in the same room with her, gave Héctor the creeps. His own mother had visited curanderas regularly in Namiquipa and the surrounding villages, and no good had ever come of it—rather the opposite. Also he did not believe such dire measures to be necessary, at least not yet.

“I am an experienced historian,” he reminded Jesús “Eddie.” “If I can discover new things about Pancho Villa, things that have never been known to anyone before, maybe I can learn where it is we should dig for the treasure. I will give myself a month to do this in. If I fail, then I will consult with Beatriz’s curandera.”

“In order to concentrate properly you will need to drink a lot of beer, amigo,” Jesús “Eddie” assured him. “We must meet here every night, and talk over everything you have found out that day.”

Héctor compressed his lips to a thin line. He could not help feeling somewhat annoyed. Jesús “Eddie” was effectively unemployed, and living off his wife.

“Don’t forget, I have a business to run, as well as search for treasure,” he reminded his friend, tartly.

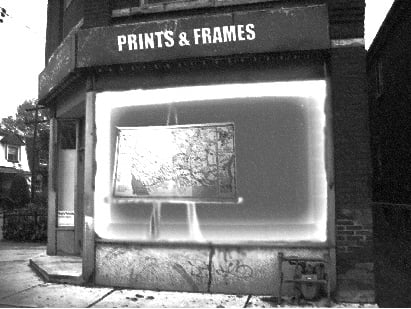

“Buried treasure” was inseparable in his mind from “map,” and so it occurred to Héctor to resume his search by scrutinizing every map of the area he could lay hands on. A shop in Los Lunas had for a year or more kept in its display window a hand-drawn map of territorial New Mexico—perhaps two-and-a-half by three feet—which he had admired for nearly as long. In addition to cities, towns, wagon roads, railroads, and trails, the map had marked upon it historical incidents summarized in a crabbed hand at the sites where they had occurred. Recognizing that this map might well be useful to his enterprise, as well as valuable in itself, Héctor resolved to purchase it, if the price were small enough to escape notice by AveMaría. As yet, he’d said nothing to his wife regarding the treasure quest, for fear she’d tell him to stop wasting his time and devote his energy to drumming up new service contracts instead of pursuing wild-goose chases in the desert.

Héctor, who’d half expected to learn the map had been sold already, was greatly relieved to find it still on display in the window. He parked out front and entered the store. It turned out to be a frame and print shop, rather more elegant than anything he was accustomed to patronize. Though somewhat intimidated, Héctor walked boldly enough to the rear of the place, where an Anglo who appeared to be in his early thirties was seated on a stool behind a tall desk, at work with a straight rule, an elbow rule, and a pencil. At Héctor’s approach, he looked up from the desk and smiled with polite reserve. The young man had on chinos and a blue golf shirt with a golden sheep stitched over the right breast. His owlish glasses were horn-rimmed, and a wing of smooth flaxen hair fell almost over one lens. Héctor wasn’t certain he cared for the type.

“May I help you?” the young man asked.

Héctor turned round halfway and gestured toward the front of the store with his thumb. “That map of New Mexico in the window,” he said. “I’d like to have a look at it, please.”

“Of course.”

The shop owner slipped from his stool, crossed to a wide desk, pulled out a drawer, and drew a large sheet of paper from it. He placed the sheet on his desk over the one on which he had been working and smoothed it with his hand.

“There you are,” he said. “Hand-drawn territorial map of New Mexico, from the late 19th century.”

“I want the one in the window,” Héctor told him.

“Why, they’re all the same—facsimiles, you know. I believe the original is in the State House in Santa Fe.”

“You mean, it’s a copy—there’s a lot of them out there?” Héctor didn’t trouble to hide his crushing disappointment.

“Sure. They’re run off all the time—very popular with newcomers to the state. Only twenty-five dollars apiece, by the way.”

So much for secrecy, Héctor thought. On the map, he located the boundary notch just west of El Paso and traced with his finger the northwesterly course of the Rio Grande. The drawings and lettering were crowded, dense, and scratchy, very hard to read. “Does it show an Apache raid on a Spanish caravan on the Camino Real in the middle 1600’s?” he asked, after searching in vain for almost a minute.

“I don’t know, let’s see.” The young man turned the map to face him and bent close above it. “Rather difficult to read, but no, I don’t think so,” he concluded, lifting his head. “Of course, such attacks were frequent. Nearly regular occurrences, for decades.”

“Then who would know?” Héctor asked in dismay.

The shop owner, noting his desperation, looked surprised. Then he smiled. “Someone at the university, perhaps? You might look there.”

Héctor felt certain that, his type or not, this was a good young man. “Can you recommend anyone in particular?” he asked gratefully.

“Well . . . You could try Dr. Salbador—Salazar Salbador—on the Valencia campus. Comes in here all the time, looking for stuff to do with the Southwest border area and so forth. They say he’s an expert on the subject.”

Chiefly from gratitude, Héctor went ahead with the purchase, counting out $25 from his wallet while the young man rolled the map tightly and inserted it into a cardboard tube. The sum was small enough to escape AveMaría’s notice, and besides, he was paying in cash.

It took him three days to run Dr. Salbador to earth in his faculty office between classes. The Professor was a small, thin, weak-chested man in his thirties, with a sallow complexion and wild hair shot prematurely with gray, dressed in work boots and jeans and wearing rimless glasses jammed back into his eye sockets. Héctor disliked him on sight. University hippies and radical types had never been his favorite sort of people, ever since his own days at school.

“I’m sorry to be a nuisance,” he began, “but the man from the print shop suggested I talk with you.”

Dr. Salbador heard him condescendingly. The walls of the cramped, disorderly office were covered with Nation of Aztlán and faded César Chávez posters and a number of framed historical prints.

“Jeremy Spode,” he agreed. “He is an OK person, for an Anglo.”

“He said you’re an expert on border stuff.”

The Professor smiled humorlessly. “I am an activist on the border, not an expert,” he corrected.

“Anyway, you know a lot about it—right?”

Dr. Salbador looked smug and ran his fingers through his hair.

“I’m looking for information about an Apache raid on a Spanish caravan on the Camino Real in the mid-1600’s, I think it was. The Indians are supposed to have stolen a lot of treasure from it and buried it in the mountains somewhere around here.” Since the Professor did not at all look like a treasure hunter himself, Héctor considered it safe to mention the hidden plunder.

Dr. Salbador stared at him as if he were a bug. “First, I should not have to tell you, a Chicano, that it is incorrect to speak of ‘Indians’; they are ‘indigenous peoples.’ Second, the indigenous people you speak of did not ‘steal’ anything. They simply took what was rightfully theirs. Third, I do not acknowledge the Spanish criminals and their genocidal empire. They do not exist for me. I would never teach my students about the history of those people. I would not teach them about the history of El Norte either, except they need to know about it if they are to destroy it, and recover their land and their heritage—to recreate the historical Nation of Aztlán!”

Héctor perceived that his first impression of this man had been an accurate one. “How can you wish to destroy America?” he demanded in an unsteady voice. “America has given you everything you have—freedom, equality, human rights, equal opportunity, a good job. If you hate it so much, why don’t you go back to Mexico and leave us Americans in peace?”

Dr. Salbador’s stare of murderous hatred would have done credit to Rudolfo Fierro. “You are a Twinkie,” he hissed; “—brownish on the outside, white on the inside. Get out of my office! I have students waiting outside to see me.”

So Héctor got. He could not help noticing that the students lining up outside the door looked exactly like Dr. Salazar Salbador, only younger.

It was apparent to him now that he must consult with the curandera—the bruja—despite his misgivings, indeed his fear. (If even a Catholic priest disapproved of such a person, what would Bro. Billy Joe have to say?) Héctor dreaded the prospect of confronting her amidst an array of vials, potions, and witch’s brews; he felt like a character out of The Exorcist. But there was no other way he could see to locate the treasure. So that evening at the Taberna Aztlán (who, Héctor thought indignantly, had ever thought to give it that name?), he reluctantly informed Jesús “Eddie” of his decision.

Beatriz Juárez arranged for the consultation. The curandera’s real name was Alicia Montano, but she was known professionally as Carmen Cortez. Though she and her husband lived in a handsome house in a new subdivision north of town, her office or studio or whatever you called it was in a crumbling, small adobe house a block from the railroad tracks downtown, where the better sort of Catholic was unlikely to observe her coming or going from work. As she insisted on meeting her clients at night, Héctor had to face his ordeal nearly cold sober, after no more than a double shot of whiskey at the Taberna Aztlán. He considered packing a gun under his coat when he met his appointment, but decided in the end against doing so. €

Leave a Reply