Extraordinary writing about music doesn’t come along very often, as I have been forced to notice by my own experience—as have my own put-upon readers! But in the realm of classical music, I would suggest that Donald F. Tovey’s Essays in Musical Analysis is an imposing composition, a stunt of writing—the freight of its assertions being something else again. Since Sir Donald died in 1940, I must admit that I was a bit late to the feast, but at least I got there. Another feast I was late to is also a demonstration of powerful writing, but it is a long way from being by one author.

Reading Jazz: A Gathering of Autobiography, Reportage, and Criticism From 1919 to Now, edited by Robert Gottlieb (1996), is 20 years old, but is as indispensable as it ever was in those years. It is without doubt the best thing of its kind, so good as reading that a commitment to the subject isn’t really required. But perhaps a commitment to over a thousand pages is required, though it does break down into many quite reasonable parts.

For some perspective, we would have to note that the editor has been editor-in-chief at Simon & Schuster, Alfred A. Knopf, and The New Yorker. His extended research and assembly suggests that various fugitive pieces gain in authority and power of suggestion by being aggregated as an imposing snowball—one that gains by its own going. I was not surprised by the presence and acknowledgment of European music, knowing what I know from other sources, Coleman Hawkins and Ray Charles among them. But I was surprised at what I will call a deadpan presentation of conflicts and evaluations as they were and are in the history of jazz, with no unseemly effort to paper over any looming cracks of dissent.

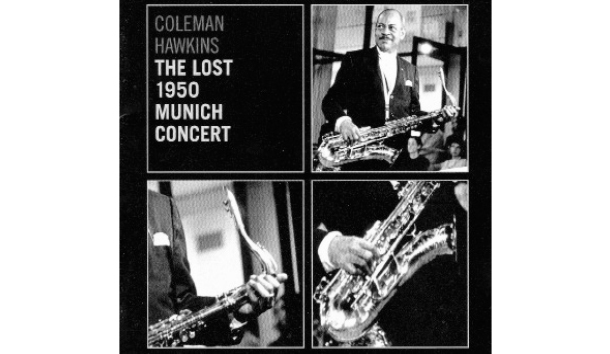

But before we look at the other sides of contentious debates, let’s review the situation of jazz as it relates to the historical presence of classical music and traditional educational practices. One good place to start would be John Chilton’s biography of Coleman Hawkins, The Song of the Hawk (1990). I had my reason for reading that volume, for I remembered the day I first heard the famous 1939 classic version of “Body and Soul,” as put across by the master of the tenor saxophone. After the first measures, I said “Whoa!” Then I said “Bach!” I was therefore most impressed to learn of an interview with Hawkins published in the New York Daily News, March 23, 1965, when he was asked to advise young musicians:

If they think they are doing something new they should do what I do every day. I spend at least two hours every day listening to Johann Sebastian Bach, and man, it’s all there. If they want to learn how to improvise around a theme, which is the essence of jazz [adding blue notes], they should learn from the master. He never wastes a note, and he knows where every note is going and when to bring it back. Some of these cats go way out and forget where they began or what they started to do. Bach will clear it up for them.

That statement must have shocked some back in 1965—it was already politically incorrect, even if we ignore the word master. But it was a worthy statement by a devoted musician who was fond of the classical repertory, played it on the piano, and collected many recordings of it.

But to return to the Gottlieb volume: There are numerous instances of jazz players acknowledging the classical precedent, or other contemporary music that competed with their own or supplied their needs. When the famous album Kind of Blue was being developed, Rachmaninoff and Ravel were on the minds of Bill Evans and Miles Davis.

I will deal only briefly with what I call dissent in the record of Reading Jazz—or writing jazz. We have dissent about history, about individuals, and about the episodic turning points and the conceptualization or even ideological accounting of jazz phenomena. Gottlieb includes the reflections of outraged conservatives without judging them, probably because the reactionary opinions are so well expressed. “The Unreal Jazz,” by Hugues Panassié (1960), is a denial that bop is jazz at all. “All What Jazz?” by Philip Larkin (1970) seconds the motion, and argues that bop is simply modernism.

Looking back on a century of jazz, the decades are not so challenging to classify. Jazz is a salient part of an age in the 20’s—The Great Gatsby is a marker of the penetration of jazz into society and its association with alcohol, speakeasies, and fraud—and with the Mob as well. Jazz was a phenomenon that everyone was aware off, with the fast women, fast cars, and fast money. The 30’s were different, and jazz adjusted both to swing music and the attention of youth, and to cultic evasions of popular preemption. By the late 40’s, the future of jazz—now its past—was set: The young Miles Davis played with Charlie Parker, and a great deal of attitude and position was laid down. The occultation of jazz was justifiable in several ways—as a course of conceptual development; as a shield against co-optation; as a refusal of cheap and damaging popularity; even as a racial bulwark against a white takeover that had many forms. Nevertheless, jazz was up against it. During the 50’s, rock music, exploiting the pioneering work of the electric guitarist Charlie Christian and much of the tradition of rhythm and blues, won a battle of exploitation and degradation. The particular instrumental sound and challenge of jazz had been largely discredited among the young, never to return. A fabulous fusionist like Ray Charles could do whatever he wanted, but jazz had been painted into a corner, mostly by itself, if not by the progressive mindset altogether.

Today in large part, what has happened to jazz is the worst thing that could possibly have happened: It has become academic, which is usually a sure sign that something is dead. But in that mortuary vicinity there are some recompenses, including a justifiable insistence on standards of competence and the maintenance of cultural memory. There is an unavoidable problem with nostalgia, which is an inevitable result of the industrial/capitalist model for cultural life. And also I think there is a undeniable problem with the racial aspect of jazz—a problem that has escaped reason to some degree. And there is also another particular problem that has escaped reason as well, though not in the jazz context only.

“Historicism before the event”—as I call it (I dismiss “double reverse historicism” and “double secret probation”)—is an oddly framed intellectual construct which dictates what has been manipulatively and even mystically called “the right side of history.” Jazz history illustrates the point over and over. As bop began a destructive revolution in jazz, Coleman Hawkins himself said things had to move on, and that he would adjust to them. Fair enough, but I think his own knowledge, predilections, and disposition should have taken him the other way. In my own path, I couldn’t do everything, so I pretty much quit listening to jazz after Kind of Blue. And Miles Davis never made me regret that—quite the opposite. He was the first musician I ever heard who actually projected grudgingness through music, and later, he destroyed his own identity by continuous reckless recycling. If I ever took jazz up again, I would try to find a club scene—but as it is, jazz is in big trouble.

And that’s too bad, because jazz is American music that went around the world. Jazz has not been exempted from various technological and other revolutions, and is trapped in the agony of a small, dissatisfied audience, either cultic or indiscriminate, and a museum mania of preservation, as the great years slip further away.

Jazz certainly needs something, but even before the present miseries, jazz had some serious unresolved issues, and they show up in Gottlieb’s remarkable anthology. One of those issues was race. No one I know of ever denied that jazz was a product of the black people in America, with some contributions from the Caribbean. A bit less controversially, no one denied either that the obvious instruments that African-Americans played were European instruments. There were unquestionable African aspects of black music, in gospel and church music, in the blues, and in jazz.

There was also a European background that was a part of the synthesis of jazz, in musical notation, in popular and art music, in the educational process, and so on. Jazz is an American hybrid phenomenon; it didn’t develop in Africa.

There were—decades ago and even today in some ways—tensions and abuses in business, travel, and arrangements, first in a segregated society, then in an integrated one. These problems, understandably irritating, insulting, and exploitative, are not a basis for an argument about which players of which color are the exclusively authentic performers of jazz. Musicians—of all people!—should know that musical mastery cannot be restricted by a label, or even an identity. If you don’t believe me, ask Django Reinhardt.

Musicians—again, of all people!—should also know something about another “issue,” though it is one rarely addressed today, for various reasons. I refer to drugs, and among drugs, I definitely include alcohol abuse. In Gottlieb’s book, various passages, autobiographical and other, tell us the same stultifying story again and again about the damage done by hard drugs and hard alcohol to the many gifted players who died. The imperatives of precision, memory, tonal control, intonation, and other qualities testify to what the instrumentalist cannot deny: Drugs don’t help—quite the opposite. The drugs lie, and then you lie, and then you die.

In his comments, Miles Davis is pretty tough on Billie Holiday, though he had his own problems with drugs, and in his later days behaved so absurdly sometimes that drugs might have been an improvement. Art Pepper’s harrowing account of his addiction is so wretched that the joys of jazz are drawn into question. Somewhere between drug-slavery and pseudoacademic jive, jazz must find a better way into a sustainable future, if it is to be more than a sum of its recorded past. In that sense, nothing is wrong with jazz that isn’t also wrong with the nation.

Leave a Reply