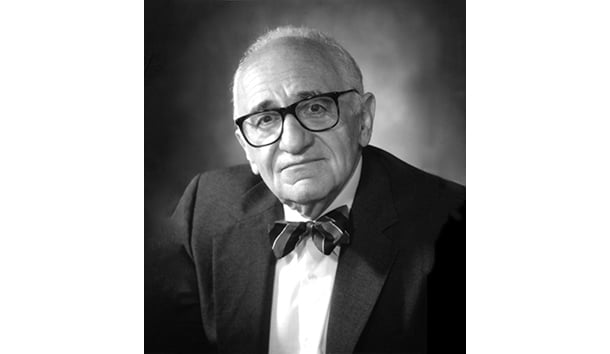

Murray Rothbard, the principal founder of post-World War II American libertarianism, died 24 years ago. Lew Rockwell, one of Rothbard’s closest friends and the founder of the Mises Institute and LewRockwell.com, offers this description of his core ideas:

If you want to understand Murray Rothbard, you need to keep one principle in mind…Murray believed in a complete free market. The State, which Nietzsche called ‘that coldest of all cold monsters’ was the enemy. In order to maintain a free society, people needed to hold certain values. Murray was a traditionalist who believed in natural law and the family. He deplored assaults on tradition such as the modern feminist movement. In cultural matters, Murray started out on the Right, and he always remained there.

Readers who want to know what Rothbard stood for need only read his major works, which included Man, Economy, and State; The Ethics of Liberty; Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature; and Power and Market.

But there was much more to Murray than his libertarian vision, or his contributions to Austrian economics and American history, which made him famous.

I last spoke to Murray a week before he died, and his intellectual enthusiasm was as vigorous as ever. In his rapid cadence of speech, he covered a wide variety of subjects: Joseph Schumpeter and the Walrasian Box; a book on Judaism; why a cause cannot follow its effect (a principle that a few philosophers deny); the O. J. Simpson case; and Hegel’s relation to the tradition of German mysticism. On each topic, he delivered illuminating insights, often punctuated by his unmistakable laugh.

Murray could grasp the essentials of an argument faster than anyone I have ever met, and immediately apply his great learning to discuss any topic. On one occasion, I had to give a joint seminar with him at the Ludwig von Mises University summer program, and Murray had just read an article by Milton Friedman about Ludwig von Mises that he hated. Murray couldn’t contain himself, and spent most of the seminar picking Friedman apart, paragraph by paragraph, barely pausing for breath. Another year, he began his seminar with a brilliant history of political power that covered a vast stretch of history, starting from Lao Tzu, through Hobbes and Locke, and ending with the public choice school. He had the literature of many different fields at his immediate command, unlike anyone I’ve ever met.

Not only was Murray’s reading vast, but he seemed able to recall with ease even obscure texts he had read long ago. He once gave a lecture on the Austrian theory of the business cycle. After the lecture, I asked whether Mises had responded to a common objection related to the expansion of bank credit. He immediately remembered the answer: “See his response to Lachmann in Economica, 1943.” I often visited used bookstores with him, in both Palo Alto and Manhattan, and listened, amazed, as he offered a running commentary on the books in each store, almost all of which he had read.

When Murray was a student at Columbia, he admired the philosopher Ernest Nagel, who he said would always listen respectfully to his students and encourage them in their work, rather than adopting the condescending and aloof attitude of some professors. Murray was like that. He was always supportive of his students and urged them to work on Austrian and libertarian topics.

His interest in politics wasn’t just theoretical, and he applied his mental abilities to analyze the political scene of his day. He of course followed presidential campaigns, but he had a detailed knowledge of congressional races as well. He could take any congressional district and tell you who was running and what the main political issues in the area were.

He was active in the Libertarian Party for a number of years, and he met many odd characters among the members. Murray was interested in all of them and often told funny stories about their adventures. His wife Joey, shared his interest in what everybody was doing.

He hated the self-proclaimed academic elite he called “court intellectuals.” He liked the common sense of the ordinary American much better. He defended Joseph McCarthy and supported the presidential campaigns of Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan. These people, he felt, represented the real America. It may at first seem odd that an anarcho-capitalist libertarian would support these populists, whose views on economics differed greatly from his own, but in fact it was not.

His fundamental political stance was opposition to a bellicose American foreign policy, and these American nationalists opposed efforts to enlist America in worldwide ideological military crusades. McCarthy argued that the main threat posed by Communism was internal rather than external, and in this Rothbard heartily concurred. He was particularly close to Buchanan, who defended the pre-World War II “isolationists” and opposed the American invasion of Iraq.

For the same reason, William Buckley and his neocon successors bitterly opposed Rothbard. They did their best to purge the right of anyone who supported a peaceful foreign policy. Rothbard, once a valued contributor to National Review, was no longer welcome in its pages once his noninterventionist foreign policy views became clear.

Rothbard liked the populists for another reason, and here we return to the quotation from Rockwell from which we began. He deplored efforts to overhaul traditional American values in favor of “political correctness.” He admired Paul Gottfried’s comprehensive critique of this project, and he joined Gottfried and other so-called paleoconservatives in 1989 to form the John Randolph Club.

One person involved in politics he admired without reserve was his great friend and fellow libertarian Ron Paul. He and Paul, along with Rockwell and Burt Blumert, worked together in defense of the gold standard, opposition to the Federal Reserve’s manipulation of the money supply, and advocacy of a noninterventionist foreign policy. It is in these activities with these friends that one finds the essence of Rothbard’s political commitments.

Naturally enough, Murray had strong likes and dislikes. He loathed Bill Clinton, and Joey told me that when he was watching Clinton speak on television, she had to restrain him from rushing to the TV set and kicking in the screen.

Like his conversation, his books were packed with material. He wanted to tell his readers the results of his scholarship. His Man, Economy, and State ranks as one of the foremost works of 20th-century economics, according to both Ludwig von Mises and Henry Hazlitt. The two volumes of his History of Economic Thought, which appeared after he died, are great works of intellectual history as well as economics. Murray Rothbard was my friend for 16 years. After nearly 25 years I still wish I could give him a call to ask him about a new book and to experience his never-failing warmth and kindness. His support for me never failed, and I owe him everything. To quote Shakespeare, “I shall not look upon his like again.”

Leave a Reply