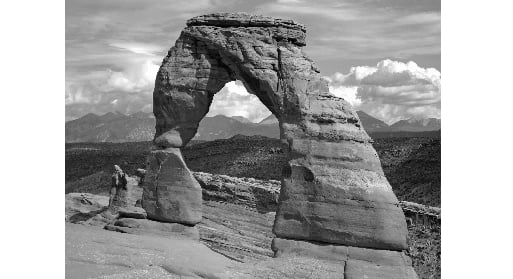

Over the weekend of March 11, our daughter, Virginia, was married in the Arches National Park near Moab, Utah. She said she wanted to be married in a place surrounded by natural beauty, well away from trite tourism. After some web-surfing, she picked the Delicate Arch (one of the most photographed natural arches in the world). It was to be a small, private wedding with only the immediate family, a photographer, a secular officiate, and a park ranger present. This wasn’t what Judy and I had always envisioned for our daughter’s wedding; but, then, it was her wedding.

I’ve traveled extensively in the West, but I’d never visited Moab, a small, rustic town catering to outdoor sports of all types and reachable by air only by flying into a small regional airport in Grand Junction, Colorado. Moab is about a 90-minute drive from there through some of the most spectacular desert and mountains in the region. The town is perched on the edge of the Canyon Lands National Park, where 127 Hours was filmed and where the original story took place; Thelma and Louise was also shot nearby in Dead Horse Point State Park. John Carter was filmed in Arches National Park. Much of the area does look like Mars, or what I’ve seen of it on TV, and there are ample cliffs to drive off of when all seems hopeless.

Virginia arranged for the whole wedding party to stay in a bed and breakfast, a particular accommodation I assiduously avoid whenever possible. In my experience, B&Bs are run by social misfits. Proprietors fashion themselves to be “people people,” but they’re more often self-directed, overly amicable egoists with poor customer-relations instincts.

B&Bs are characteristically quaint, charming, and picturesque, inside and out; they are also infamously uncomfortable, inconvenient, and dysfunctional. Our Moab inn was no exception. The grounds held a main house and a pair of small cottages. It was built in the 1850’s by a Mormon polygamist; the separate structures accommodated his several wives and children. Each cottage was tiny, ancient, and simple; but each was beautifully refurbished and modernized, offering TV and Wi-Fi. The center of the compound boasted a well-manicured garden with a large outdoor dining table under an emerging brush arbor, a term our innkeeper hosts had never heard. The main house contained four miniature bedrooms, a medium-sized dining room, and a cramped and uncomfortable parlor, with well-appointed but undersized rock-hard furniture and an electric fireplace, a feature our innkeepers were astonishingly proud of.

One of the free-standing cottages was the “Deluxe,” used as a kind of bridal suite; the other was “Garden,” plainer and just a bit more spacious than the bedrooms in the main house. Judy and I drew these quarters. It turned out to be a two-room affair, which was small enough to remind me of Mark Twain’s complaint about a hotel room: “It was large enough to swing a cat in, but not with absolute safety to the cat.” There was a private bath, an unusual feature in most B&Bs, a bedroom, and a “living area.” The bedroom was dominated by a queen-sized bed that was comfortable enough, once we removed the 12 pillows and shams, although there was no place to put them but on the floor, if we wanted to lie down. This made walking around the bed impossible without stumbling over them, so rising in the middle of the night—something older folks often have to do—was treacherous. There was a diminutive closet, made smaller by the installation of a minifridge. The closet’s single shelf was jammed with extra pillows. We could hang up about four garments. A large chest offered three empty drawers out of six, the others being full of blankets and even more pillows. There was nowhere to put suitcases except on the bed—if we removed the pillows to the floor, which made it impossible to stand next to the bed to work out of them. There was also a full-length mirror; but, with all the pillows on the floor, we couldn’t stand far enough away from it to make it useful.

The “living area” was dominated by two antique tables and a TV, a rickety ancient chair, and a pillow-piled futon, so there was nowhere to sit down, as the futon was jammed into a semireclined position, and there was no room on the floor for all the pillows. The bathroom was small; indeed, the closet, mini-fridge included, wasn’t much bigger. Outside the shower door was a raised wooden pallet, on which I jammed my toe every time I entered barefoot, and the shower itself was so narrow that I couldn’t physically turn around in it. If I dropped the soap, I had to open the door and step out in order to retrieve it. There were no towel or clothing hooks, no sink shelf spaces on the antique free-standing lavatory, and the toilet was crammed into a nook so narrow that no adult could sit on it without barking elbows on the walls. Minimum-security federal prison cells offer more space and comfort. It was, however, utterly quaint, charming, and picturesque. Every flat surface featured some kind of ancient lamp, broken clock, decorative gimcrack or gewgaw to ensure that nothing from pocket or bag could be put on it, and a portable heater took up what remained of floor space. This was also a hazard to any pillows that might have been strewn about.

The “innkeepers,” as they fashioned themselves on hand-lettered signs posted everywhere, were affable and accommodating, to a point. He, we were told, had studied under a master chef, and she had a degree in—what else?—interior design. They were delighted with themselves and friendly in a Sarah Palin sort of way. Payment, we discovered, had to be made upon check-in, and they only took particular credit cards. Breakfast, we were told, was always served promptly at eight. The menu was fixed and apparently to be a surprise each morning. We were warned to be sure to turn off all lights when we exited any area and were advised to “relax” and “have fun.”

The wedding was to be on Sunday. Forewarned that the hike to Delicate Arch was “moderately difficult,” and not being veteran hikers, Judy and I decided to leave on Thursday in order to get in a few shorter, easier warm-up treks in advance. Accordingly, I booked a 10:05 a.m. flight out of Dallas. We anticipated arriving in Moab around 3 p.m. MST.

The drive from our house to DFW normally takes about 45 minutes in heavy traffic. That morning, we were delayed by weather, two accidents, and construction detours; although we left at 7:30, we didn’t arrive at the terminal until 9:15. Once my credit card had been cleared to pay for checked bags, we were abruptly told that we were deemed “late,” although the flight wasn’t scheduled to depart for another 35 minutes. I was then charged an additional $150 to confirm on the next flight (7:30 p.m.), but the ticket agent advised me we could “run like hell” for the gate and still make it. “That’s not technically possible,” she said blithely, “but it happens.”

We raced for the security line, then stood still. Two families with four small children each were ahead of us in line. Each child had laced shoes and a carry-on and a personal item apiece, as did the parents, including strollers, car seats, backpacks, and what was apparently a collapsible tricycle. The first group had also packed two laptop computers inside carry-on luggage. These had to be removed, and the bags run through the X-ray again. The second family learned nothing while watching all of this, so the same drama was repeated, right down to the secreted laptops. Minutes ticked away, while one of the mothers had to pass through the metal detector five times, because her elaborate costume jewelry kept setting off the alarm. Three or four of the children also seemed to have multiple metal items on their persons, and one two-year-old was screaming like a banshee, afraid to go through the full-body scanner alone. The TSA officers, whose principal occupation, it seems, is to protect us from people dumber than they are—a very small pool—offered unhelpful and loud, irritable announcements about what could and could not be taken on board, and otherwise made no effort to hurry things along.

Judy got through first and raced, barefoot, for the gate, only to find that they had changed the terminal for our flight. It was now 9:55, and the new terminal was at the other end of the airport. Besides, we were told, they had released our seats to standbys.

I immediately called the B&B and the rental-car agency in Grand Junction and notified them of our pending late arrival. It was still pouring rain outside, and the only movies playing in the area were pitched for idiot children or the young teen crowd, so we had few options. Not wishing to return home and wait, only to fight rush-hour traffic on the return, we went to a local mall and walked around for six hours. When 5:30 came, I called to confirm the 7:30 p.m. flight, only to find that the terminal had again been changed and that the flight was delayed until 8:15. When we arrived at the airport, we found that the gate had changed again; the flight was now delayed until 9:20. Over the next four-and-a-half hours, we experienced four more gate changes and four more delays—none of which was publicly announced, and all of which required more calls to the B&B and car-rental agency. After becoming intimately familiar with the terminal’s sterile amenities, we finally took off at 10:45 p.m., arriving in Colorado at 12:45 a.m., more than 12 hours late.

The rental-car agent stayed open for us, but we were in no shape to drive that far in the dark, so we checked into the first place we saw, an ancient motel near the airport. We hadn’t planned to spend a night in transit, so I had to drag all our bags up two flights of stairs. We also hadn’t eaten since lunch, but I found an open convenience store and bought some yogurt. We got to bed about 3 a.m.

On Friday, we rose early and reached the B&B about 10 a.m., without further incident. The scenery was spectacular, but we were growing anxious about scheduling. It took us two hours to check in, since our innkeepers insisted on giving us a full tour and history of the facility. They were particularly adamant that we understand what the sign Please Service Room meant and that we learn precisely how to hang it on our door if we wanted our room cleaned. After inspecting the room, I determined that, by the time we got our bags inside, the only way anyone could change the sheets on the bed would be if they threw our belongings and all the pillows out a window, so I decided to forgo maid service.

I held hope that they wouldn’t charge us for the previous night, since our absence wasn’t our fault and they had no other bookings; they also didn’t have to make us breakfast that morning. No luck. Their policy was 48-hour cancellation notice. The tour and explanations and warnings and policy statements, then semiunpacking in the tiny quarters and trying to keep dress clothes for the wedding from totally wrinkling, consumed our warm-up hiking time. Virginia had arranged for us to have a cheese tray in our room for what she thought was to be a late arrival the night before. That provided lunch, which, fortunately, we were able to eat al fresco; had it been raining, we’d have had to sup standing up in our room, putting numerous pillows at risk. At that point, Suzy and Jeff, Matt’s parents, showed up. After greetings and amenities, it was after three, so we prowled the two city blocks of downtown Moab and marveled over all the authentic Native American and locally significant artifacts and souvenirs, most of which were made in China. Then we returned to meet our future in-laws for dinner.

Our innkeepers helpfully directed us to a Mexican restaurant they said was “extra good” because “all their food is organic.” Although that indicated to me that they knew nothing about Mexican food, we took the recommendation. They said it was an easy walk. Ten blocks of uphill trudging later, we asked directions of a guy in a bike-repair shop, who said it was three blocks farther. Still uphill. Moab is about 4,000 feet above sea level, and we were all flatlanders, wheezing for breath. We hiked it anyway, only to find the restaurant shuttered and out of business. Famished and tired, we staggered back to an unlikely-looking pasta joint we passed about two blocks from the B&B. Our waiter, Edgar, was highly entertaining. He spoke with a slight Swedish accent, although he averred that he had been born in Mexico and had lived in Moab “all his life.” The highlight of the meal was when we asked for some bread to go with the salads. Edgar cheerfully brought eight huge chunks of garlic bread. Then, almost immediately, the entrees came, and each had two more chunks of bread on the plate. Edgar didn’t seem to find this particularly remarkable; he charged us for the extra bread, though.

In the meantime, Virginia and Matt, our son, Wesley, and his wife, Amanda (who came from Phoenix), and Scott, Matt’s brother (who came from Washington, D.C.), were all scheduled to arrive in Grand Junction between 9 and 10 p.m., rent a car, and drive to Moab. Judy and I laid in some beverages. The Charneys provided snacks. Scott’s plane, though, was delayed. (He was rerouted through Houston at one point.) He didn’t actually get on the ground until midnight, and his luggage was lost. By that time of night, there was no one left at the miniscule airport to talk to about it, so they just came on. As we waited at the B&B, the weather turned chilly, so we adjourned to the miniature parlor and its rigid, undersized furniture. Wes drove the 90-minute trip in an hour, and eventually everyone arrived and retired. Again, bedtime was about 3 a.m.

Although our innkeepers had told me we would be the only guests for the weekend, another couple had checked in late Friday night, and they were up promptly at eight for breakfast. Bicyclists, they were disgustingly healthy and obnoxiously cheerful. The Charneys were disinclined to leave the B&B before Scott’s lost luggage arrived, so while Virginia and Matt went to pay for their marriage license and park permit, Wes and Amanda and Judy and I went to take an “easy” hike to Mesa Arch.

The trailhead for Mesa Arch is in The Canyonlands, and the hike is about a mile long at only a slight grade on an established trail. It was mildly taxing but doable, and the weather warmed up and was gorgeous. Mesa Arch was remarkable in its simplicity and beauty. The view from the promontory is panoramic, taking in the “Island in the Sky” and overlooking 300 miles of protected wilderness, mostly canyons and valleys surrounded by jagged mountains and snow-capped peaks. Deep purples and sharp greens contrast with soft yellows and dark grays to offer a panoply of colors against a vast natural frontier that stretches to the horizon. It was amazing—and exhausting for sleep-deprived people, and we stumbled back to the cars, already weary, although it wasn’t yet noon. We returned to the B&B, finished off the snacks from the night before, and then, assured of a second wind to come, all of us went for a “moderate” hike to Corona Arch, a round trip of about two miles over unimproved trail.

Excepting a few places at the outset, this trek wasn’t much steeper than that to Mesa Arch, but it was longer and more rugged. It furnished a breathless warning about the next day’s plan. The march up went well, though, and Corona Arch, which we viewed from about 500 yards, was splendid. Climbers were rappelling off the top of the enormous golden structure. Naturally formed caves and enclaves on the surrounding mountains are covered with pictographs from ancient tribes, and the harsh yellow-and-red barrenness of the terrain is striking in contrast to the translucent blue skies and silvery waters of the upper Colorado, which winds gorgeously through the area.

That night was what would have been the “rehearsal dinner,” if we’d had a rehearsal, which we didn’t. Virginia forbade any of us to see the wedding location in advance. Still, we had what we called the “groom’s dinner” in a small steakhouse where Jeff Charney had made arrangements weeks before. We returned to the B&B about 11, where our innkeeper informed us that, in spite of our sincerest requests, he couldn’t compromise on the checkout time the next day. The rooms had to be cleared by 10 a.m. The wedding was scheduled for 7:30 a.m., so, mindful of the distance as well as the time change that was taking place overnight, we all set about shoving pillows around to open our bags for packing. It was well after one before we retired.

Sunday, Wedding Day, started out clear and about 27 degrees. We were to be at the trailhead for Delicate Arch by 6:15 a.m. When we arose at 3:45 a.m. and dressed and completed packing, Virginia was already up, doing hair and makeup with Amanda and her sister Kate, who had arrived the afternoon before and had the good sense to get a regular motel room nearby. Our innkeepers had promised that they would have coffee and sweetmeats for us to take along, but in the predawn darkness, there was no sign of either of our hosts, no light on in the residential cottage, no coffee, no pastries, no nothing. I drove around the tiny town and found a McDonald’s, the only place open at four in the morning, and brought back several coffees. When I returned, Wes went back for a half-dozen sandwiches. I tried to ignore the oddity of breaking our fast with Egg McMuffins at a B&B.

By 5:45 a.m., we were all on our way. Our innkeepers had assured me that it was a 25-minute drive. I had the foresight and, now, experience with their veracity to seek a second opinion. The counter girl at McDonald’s said it was more like 45 minutes, as the speed limit in the park was only 35 mph, and it was a twisting, winding road to the trailhead. When I reported this, Virginia immediately panicked. She took over driving the lead car, and we made it in 20 minutes, racing through inky darkness about 60 mph and skirting what we later realized were sheer drop-offs around the switchbacks. When we arrived at the trailhead, the park ranger and officiate and photographer were there and ready. After a quick personal break—since there were no facilities where we were going—and laden with backpacks full of wedding garments, snacks, and water, we started up in the dark.

The trail was advertised as a “medium difficult” climb, about 1.5 miles to the Delicate Arch. It felt more like three miles, and it was all—I mean all—straight up and exceedingly strenuous. The footing was treacherous, as the surface varied between broken rock and smooth sandstone, called slickrock. The grade of ascent ranged from 30 degrees to about 60, with no flat spots to stand and rest and catch a breath—a good thing, as pausing encouraged stopping, and stopping encouraged giving up, something no one wanted to do. It was pitch dark for much of the early going, finally lightening into false dawn. Judy, who is acrophobic, would never have made it but for Amanda and Kate, who stayed with her, talking her past the sheerer drop-offs and over the more jagged footing, while Wes walked with me, unnecessarily asking if I was “all right” every ten steps. We were now at about 5,500 feet and were huffing and puffing, thinking of the hours of sleep we didn’t get and the meal we hadn’t eaten at the bed and breakfast. As we approached the summit, there was a narrow ledge slanted down about 30 degrees toward a 200-foot drop-off; this slender, tilted pathway ran for about 25 yards and rose steeply around the mountain face. We navigated that, one foot in front of the other, not daring to look down, focusing on balance and gasping for air until we rounded the bend.

There it was.

The Delicate Arch was nothing short of spectacular. Unimaginably huge, it stood vivid against the pre-dawn sky. It was singular, exquisite, wondrous; we’d have had no words to describe it, even if we could have stopped panting long enough to say anything. With a magnificent rocky background festooned with naturally formed, wind- and water-etched stone towers and lesser arches all around, it stood a lonely sentinel over a rugged, wild desert mountainscape. Small wonder that the state of Utah depicts it on license plates. It was stunning to behold, utterly breathtaking, if we’d had any breath left to take.

The immediate problem, though, was that there was a waist-high shelf of large boulders that had to be traversed to get to it. From our ledge, this was the only approach to the arch. One had to cross over the rocks, then pace carefully around the rim of a naturally formed basin of extremely smooth and slippery rock that was shaped like a huge, deep mixing bowl, about 100 yards in diameter, rimmed by giant boulders on three sides and sharply descending in a kind of whorled vortex of sandstone to the bottom, several hundred feet below. Judy declared it was impassible. But the Charneys were already past it, as were Virginia and Matt, so with us all encouraging her and helping, she somehow managed to climb up and scoot over it and into the rim of the basin, then thread her way carefully around the edge to the opposite side.

The officiate, a local radio DJ with a license to marry people—something of a recycled hippie—was already there, “cleansing the air” with burning cedar; and the photographer, a rock-climbing guide by trade, was leaping around, hanging off impossible shelves and standing at impossible angles to get advantageous shots.

The women in the wedding party “changed,” which had to be done more or less in the open, as there was no cover anywhere. While the men turned their backs, the women set about removing backpacks, parkas, pants, then donning bridesmaids’ dresses—or, in Virginia’s case, her wedding gown—and exchanging robust hiking shoes for dress heels. All this was done at steep angles, with nowhere really to stand and easily balance and nothing to hold onto. Footing was slick everywhere. The temperature, according to the ranger, was 40 degrees, but the skies were crystal clear, a light breeze had kicked up, and everyone was shivering.

Finally, the party gathered under the arch, and Virginia appeared, in gown and heels, looking beautiful, and I gingerly escorted her, toe-to-heel, down a steep decline to the edge of the abyss and a spot directly under the arch, where she was, at last, as the sun broke over the adjacent summit, filling the mountain pass with brilliant golden rays, married to Matthew Charney. The ceremony was short, sweet, and perfect. Judy wanted to cry and to reach out to touch her daughter, but she was terrified of falling, so Wesley and I kept hold of her.

The officiate said that if the newlyweds were lucky, a raven would appear. Ravens mate for life, and seeing one on a wedding day was a very good omen. Sure enough, I spotted a pair of the birds just as the ceremony concluded. They lit on top of a high precipice and were beak-to-beak as the sun hit them, as if posing for photographs, which were taken amidst expressions of astonishment. The photographer took Virginia and Matt up to a high tor to get a shot with the valley behind, but on her way down, Virginia’s heels failed, and she fell and skidded down, skinning both elbows with abrasions that immediately started bleeding. The ranger offered her some tissues, though, and she toughed it out; after a half-hour or so, we were done, much to the relief of about a dozen irritated hikers who had arrived just as we finished the ceremony and whom the ranger had held back.

We began the descent. It took a bit less time to go down, although the going was rougher because of the fear of slipping on loose and broken rock; and now, we could see how far we would fall. Virginia and Matt lingered with the photographer to get some more shots at special areas he knew. Amanda and Kate kept up a running conversation with Judy, encouraging her over the dangerous places and keeping us all moving. Along the way, we encountered dozens of hikers coming up, some 20 years older than we, making us feel sheepish. Many, though, were discouraged when we told them they were less than halfway to the arch. One woman, seeing our white shirts and ties and backpacks, said, “We didn’t get the memo about having to dress up for this hike.”

I replied, “Oh, we’re Christian missionaries coming to reconvert the Mormons!”

Our innkeepers, who were catering the wedding luncheon under the unfinished brush arbor back at the B&B, had insisted that I call to give them a heads-up on our departure so they could start the meal preparations. There was no accessible cellphone tower anywhere in the park. I wondered why they were unaware of that.

When we arrived, to their credit, they had done it up brown. He lived up to his training as a chef, although he neglected to provide a preordered vegetarian meal for Scott, and she seemed unaware that she was to perform waitress duties. A long table was beautifully set under the half-grown arbor. The wedding cake for which Virginia had arranged arrived and was beautiful. Native American flute music was on the sound system, there were flowers, the champagne was chilled, and all was in readiness. The meal was fine, the ceremonial portions of it came off great, and things were happy and festive. It was, again to our innkeepers’ credit, a lovely and memorable setting, if a little warm, as the temperature rose to about 80 degrees, and the sun was bright and hot. But no one complained, and we did all the usual wedding rituals except dancing, which was not wanted or even possible.

Our innkeepers then informed me that the bill for the catering had to be taken care of by cash or check. As I wrote it out, he thoughtfully pointed out that the gratuity was not included. I tacked on about 18 percent, figuring they could take the rest out of their raw profits from unslept-in beds and unprepared breakfasts.

As the new B&B clients arrived at three for their “unique and picturesque experience” and requisite pillow shuffling, we bade adieu to the newlyweds and returned to Grand Junction for the night. We had reservations at a chain motel near the airport. It turned out to be brand new, offered excellent service, a large and comfortable room, an oversized television, fast and efficient Wi-Fi, ample closet space, a capacious bathroom, an ironing board, plenty of extra towels, and only two pillows on the bed. The next morning and for no additional charge, they provided a full breakfast with lots of variety served during a two-hour window, and check-out time wasn’t until noon. And all of this ran about one-third the cost of a night at the B&B. Wes and Amanda flew back to Phoenix; Kate drove back to Durango. Virginia and Matt stayed overnight in the B&B, before embarking on a wedding trip—first back to Arches, where they camped on the side of a rock, then on to Bryce Canyon and Zion National Park for the rest of the honeymoon.

In all, it was an incredible, wonderful, and certainly memorable experience. Virginia drew an ace with the weather, the photographer, and officiate, with all the paperwork and the arrangements. The B&B wasn’t quite what it might have been, but it was about typical for one of those ridiculous establishments—overpriced, awkward, troublesome, and difficult to deal with. For all its drawbacks, though, it was a perfect location, as we were all proximate to one another, and, because the weather was good, we could gather outdoors. The airline mix-ups were what they were. (Scott’s plane out of Grand Junction was delayed and we left him sitting at the airport there, being rerouted again.) But the few hitches and bumps were endurable and did not spoil anything. Virginia was a beautiful bride; Matt was splendid all around. He’s a welcome addition to our family, very handsome, strong, and devoted to her. That they truly love each other is obvious. We really like our new in-laws, and they seem to like us. They clearly are charmed by and pleased with Virginia.

It was a modest but highly unconventional start to what we hope will be a long and marvelous future. The ravens may have been the most reinforcing aspect of the whole thing, in a way, but the kids’ happiness will always be anchored in what may have been the most moving and unusual wedding I’ve ever attended or certainly expect ever to participate in. It was exhausting and physically demanding but satisfying, and the Delicate Arch was nothing short of marvelous, especially at dawn, particularly for a wedding. But the binding notion was that the whole adventure was so very much Virginia, in every way, reflective of her determination, her drive, and her dedication to being unique and doing things her own way. She is my daughter, without any doubt, and I am proud of her, pleased with her, and I love her beyond reason.

Leave a Reply