“A Manifesto for Renewing Liberalism” is the title of a recent issue (September 13, 2018) of the house journal of liberalism, The Economist. I read this confessional admission with amazement. Can the editors mean that liberalism needs to renew its vows? It is not like liberalism to be crippled by self-doubt. What went wrong? Of the myriad answers that swarm to the mind, I name just one: Africa.

Africa continues to refute the ideals of high liberalism. The continent stands at the head and front of the great liberal delusions, and the last half-century has seen the crushing of liberalism’s hopes and predictions. For our purposes, the liberal ascendancy reached its apogee in the post-World War II era. The colonial powers had been greatly enfeebled by the war, which had also seen the rapid rise of anticolonialist independence parties. And Africa, led by Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana (1957), demanded and got its independence in a rapid series of Western capitulations. “The wind of change,” in British Prime Minister Macmillan’s phrase (1960), called for no less. The liberal media orchestrated an unending call for Africans to be freed from the burdens of their colonialist masters. France, Britain, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Portugal—all fled, pelted by the organs of liberal thought. The postcolonial independence movements discovered new concepts, Pan-Africanism and African unity, though there was no pre-existing concept of Africa. As J.M. Roberts wrote, “Until Europeans took the idea to Africa, no African knew that he lived in a continent which could helpfully be thought of as a whole. No African knew he was an African, until his European schoolmaster told him so” (The Triumph of the West). Shakespeare had already captured the exultant liberation moment in The Tempest, when Caliban sees his chance to kill Prospero and rape his daughter (Act 2, Scene 2):

’Ban, ’Ban, CaCaliban

Has a new master—get a new man.

Freedom, high-day! high-day, freedom! freedom, high-day, freedom!

It makes for a rousing chorus for the Part One interval.

Part Two in real history followed shortly. The Belgian Congo collapsed in a welter of blood and raped nuns, and the sinister Patrice Lumumba became leader for a while. (His memory lives on in the Congo’s popular Lumumba cocktail: chocolate milk and brandy.) After his deposition and death, the Congo was taken over by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. He ruled as president from 1965 to 1997, during which time he became by far the leading African kleptocrat in a crowded field. In 1984 the nation’s debt was computed by economists at around four billion dollars, and Mobutu’s net worth, with a pleasing symmetry, at four billion. While the population lived in abject poverty, Mobutu spent much time and money in Europe, especially in his Riviera chateau at Cap Ferrat. He was overthrown in 1997 and died shortly after in exile, in Morocco. It is not known how much of his financial legacy has been identified; much went into his capital, Gbadolite, Mobutu’s birthplace, which became “the Versailles of the Jungle,” complete with an airport that could and did accommodate a Concorde. It is now reduced to a few domestic flights per week to Kinshasa. Gbadolite, looted after the coup that dismissed Mobutu, is a decaying shadow of its past grandeur.

The Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s novella (1902), is the essential companion to postliberation Africa. It depicts a white ruler, an ivory trader, who becomes mad after exposure to total power among the Congolese: Its chilling finale is “Mistah Kurtz—he dead.” What Conrad did not say is that African rulers go mad, too. Take Jean-Bédel Bokassa, emperor of the Central African Republic, 1966-79. He seized power after independence from France, and bribed and manipulated his Western sponsors, making good use of the diamonds which were a major currency for him. Some were given to the appreciative French President Giscard d’Estaing. Napoleon was Bokassa’s model, and his 1977 coronation followed Napoleon’s, with the entire ceremony managed by French designers. No pope crowned Bokassa, so the emperor, enthroned between the wings of a giant eagle, crowned himself and then crowned his empress. Bokassa became an embarrassment even to the French, and they arranged for a coup while he was abroad. The emperor was then exiled to France, where he would have done well to stay, but he returned to Bangui expecting a hero’s welcome. He was at once arrested and put on trial for murder, theft, and cannibalism, the bodies of his enemies having been kept in a fridge. This seems to have been not only a personal taste but also proof of the extraordinary powers and longevity so well regarded by his tribal supporters. Bokassa did, however, replenish the stock of Africans, having fathered 62 children. His death sentence was commuted, and he lived quietly in his wife’s run-down townhouse, dying in 1996. He must have mused on St. Helena.

For the real thing, consider Idi Amin, Uganda’s President for Life (in the event, 1971-79). He started life as a corporal in the King’s African Rifles, and his British superiors thought him “a splendid type . . . but virtually bone from the neck up.” After independence he became a colonel in Milton Obote’s new regime, then organized a successful coup. A killer regime of terror ensued, targeting anyone capable of opposition. The accepted figure for his mass killings is 400,000. Truckloads of bodies were dumped into the Nile. He expelled all the Ugandan Asians from the country. In England, though, he became a joke, satirized every week in Alan Coren’s Punch column, “Our Man in Kampala,” and immortalized in Private Eye’s “Ugandan discussion,” an ever-useful code word for sex. “The King of Scotland” was one of Amin’s self-awarded titles, hence the film The Last King of Scotland (2006), which won an Oscar for Forest Whitaker. The town of Entebbe was pivotal in Amin’s downfall, following the hijack of an Air France jet by pro-Palestinian terrorists. The plane, carrying 105 Israelis, was allowed to land at Entebbe Airport. Amin cooperated with the terrorists until the Israelis struck back with a daring commando assault which killed all the terrorists and saved all but four of the hostages. This defeat was a mortal blow to Amin’s prestige. Driven from power after an abortive invasion of Tanzania, he found exile in Saudi Arabia, where he lived out his days on the top two floors of the Novotel hotel in Jeddah. As was the form for deposed tyrants, he died in bed. The fortunes of his 30-odd children are not known.

Rhodesia is a country whose name is confined to history. After independence (1980) it became Zimbabwe under the rule of Robert Mugabe. He honored the fundamental law of African countries: one man, one vote, one election. There were indeed elections held, always in circumstances that gave victory to Mugabe’s party, ZANU-PF, which has ruled from 1980 to this day. After crushing his Matabele opposition, Mugabe’s prime policy was the expropriation of the land of white settlers, which brought to ruin the most successful economy north of South Africa. Archbishop Desmond Tutu called Mugabe “a cartoon figure of an archetypal African dictator,” and from 1980 to last year he fully earned that judgment. Mugabe still lives, but was deposed in November 2017 by an army fearful that he intended to name his wife Grace as his successor. The latest election has led to Emmerson Mnangagwa as disputed leader, while Mugabe continues to enjoy his presidential pension and much of his wealth. Zimbabwe can stand for the continent’s problem. As Boris Johnson has said, “The continent may be a blot, but it is not a blot upon our conscience. The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more.” Preceded by white flight, Zimbabweans migrate, if they can, across the border to South Africa.

South Africa remains a locus for judgment on the postcolonial era. The end of apartheid, and the installation of Nelson Mandela as President of the Republic, came with great hopes. To appearances the changeover went well: The imposing South Africa House in Trafalgar Square, a few yards away from Canada House, was simply occupied by different personnel. But the problems and tensions of pre-independence have not gone away. The present government of Cyril Ramaphosa is intent on replicating the policy of Zimbabwe: the appropriation of white-owned property. He is the hallmark of postcolonial Africa. As R.W. Johnson notes (“Is South Africa About to Fall Apart?” Standpoint, June 2018), “Everywhere in independent Africa a small successor elite grabbed all the key political and bureaucratic positions and used them as a source of personal enrichment. There was no parallel in the pre-colonial situation for the gross inequalities that this produced . . . ” While the black bourgeoisie succumb to the siren song of enrichissez-vous, the mass of the population sees no change in its lot. Unemployment has tripled since independence. Municipal budgets are spent on the salaries and perks of councillors. Tribalism governs corruption, and corruption rules. Civil violence is on the rise. Economic growth will not serve to stabilize the country, and the huge demographic swell is the unmistakable warning—to Africa, and to Europe and the United States.

How did this global catastrophe come to pass? Roosevelt’s insistence to Churchill and other colonial powers that they must liberate their colonies and dissolve their empires was the beginning of the great movement. Ideologically, the theme was taken up by the left and made the motive power of the Soviet influence over Africa. Influential writers flagged up the new order: George Orwell, the most respected voice of the left, wrote a famous article, “Shooting an Elephant” (1936), about his time in Burma as a police officer. His opening sentence reads, “In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people . . . ” I dare say he was. The descendants of the same people might have mixed feelings nowadays, since they have been ruled by an impeccably Burmese military junta ever since the coup d’état of 1962. The junta allowed the admirable but powerless Aung San Suu Kyi to front for democracy, but she failed to stop or even condemn the latest exploit of the generals: the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, of whom some 200,000 were expelled from the country. This deed went before the U.N. Security Council only for Russia and China to veto a motion. Even the left, which had been forgiving to the Burmese generals, is now outraged. But in the 1930’s and later the left had decided that imperialism was bad for the imperialists and worse for the governed, and Orwell was the tuning fork of that belief. They have not changed their stance since.

Other writers saw things differently and with much more realism. They had traveled and were not taken in by fashionable propaganda. Evelyn Waugh, a master of travel writing, wrote a brilliant novel, Black Mischief (1932), about the Oxford-educated Emperor Seth of Azania, and his attempts to modernize his country. Seth, whose father had been eaten by his soldiers, is overthrown and killed by his own minister. Waugh had seen the future, and like other prophets got little credit for his foreknowledge. Unlike all his other major novels, there has been no film or TV drama of Black Mischief. No doubt it is viewed as too provocative in today’s climate. Graham Greene had traveled extensively in Africa, and The Heart of the Matter (1948), set in (unnamed) Sierra Leone, offers a raspingly realistic view of Africa in the modern era. Perhaps even more striking is Paul Theroux (b. 1941), who had started life as an idealistic member of the Peace Corps. His book Dark Star Safari (2002) records an overland journey from Cape Town to Cairo and his growing disillusionment with the new, independent Africa. He particularly loathed aid workers, and if he had been writing in recent years would have made much of the sexual exploitation which came so easily to those validated—and covered up—by the charities that employed them.

Beyond politics, another area of liberal illusions about Africa involves its art. The most popular history of Western art is E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art. The key word here is “story.” Western art is ceaselessly evolutionary, moving its narrative to ever-wider levels. And it is self-aware. In the Italian Renaissance the artists of Florence, Rome, Venice, and Naples moved around and knew the work of their competitors. Since then artists have observed, borrowed, and created their own vision. The best transferred their talents like free agents in American sports; the German Holbein came to Henry VIII’s court, where his genius is still on display. Western art has a plot line; African art, by contrast, is rooted in the tribal practices of its region, which could hardly be extended beyond that region. Masks and sculptures are the basic resources of much tribal art, and are properly recognized as artifacts. Three-dimensional work is preferred to two-dimensional, and African art is not much interested in figurative accuracy. There is great variety of coloring, which operates on non-Western codes. These qualities appealed, nonetheless, to Western artists, who were much influenced by them—Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse. African chic has long been part of the European art and social scene, nowadays fostered by (mostly) left-leaning celebrities in film and pop music (Angelina Jolie, Bono) whose public work combines charities and self-promotion. But we are a long way from The Story of African Art.

Of the Western infatuation with African art, just two words resonate above all others: elephant dung. Chris Ofili (of Nigerian stock) won the Turner Prize (1998), that carnival of self-promotion, for his exhibition at Tate Britain of work garlanded with elephant dung. This substance has many uses and was prized in African societies, at least before the elephants started being killed off. Lumps were attached to Ofili’s canvases directly or used to support them. The rationale, given with all the panache we expect of art commentary, was: “His paintings are concerned with issues of black identity and experience and frequently employ racial stereotypes in order to challenge them”; they “recalibrate fixed notions of beauty.” Anyone challenging racial stereotypes holds a winning ticket, and so it proved; Ofili is now a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Africa, we are told, must be understood in African terms, rather than from a European worldview. The benign outcome is that African art thrives in the marketplace but does not challenge the astronomical prices paid for the masterpieces of Western art. Moreover, there’s a long way to go before Western ideas of beauty are recalibrated, and blondes have not gone out of fashion. Still, African art generates money, and Ofili’s work sells well in New York and London.

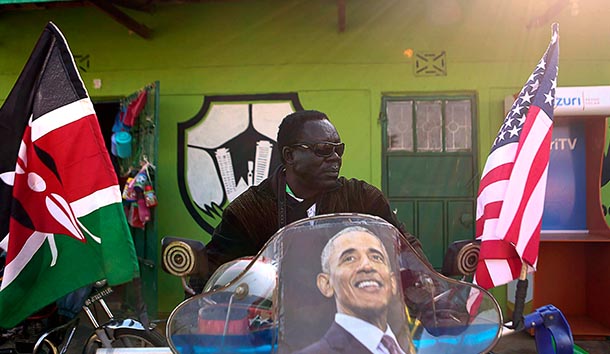

Which brings us to the African economy. President Obama made the startling claim in 2016 that Africa’s gross domestic product was the same as France’s. This claim has been rigorously fact-checked, and it seems to be about correct. It rests, however, on the fact that there are no statistics at all available for several nations in recent years, and there has to be some doubt around the edges. There is no question that continental growth is well up. But the high hopes for the growth of the African economy rest largely upon its potential, a salesman’s word. The long historical development that produced contemporary, democratic Europe cannot be compressed into a few decades, and it is impossible for Africa’s governments to produce the jobs, healthcare, and education needed for the demographic surge. Until African governments have got a grip on the ever-present corruption at all levels in society, which adds to the wealth of its elites but not to its efficiency, a certain skepticism is in order. Britain has just suspended aid to Zambia, as have Sweden, Finland, and Ireland; much of it had been stolen. The President of Zambia got the message, and the minister in charge has been sacked. As we say in the West, “Deputy heads must roll.” Nigeria has big oil together with an unequalled reputation for creative scam artists. That will continue, as will the flight of the most intelligent and best educated Africans. I think of De Gaulle’s line on Brazil: “Brazil is the country of the future, and always will be.”

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi: What is new coming out of Africa is Africans, in astounding numbers. The somber vision of Raspail’s novel Le Camp des Saints (1973) on the invasion of the First World by the Third is now well under way.

The spectacle of millions of Africans fleeing their liberated lands in order to get to the homelands of their imperialist-colonialist oppressors is, in bold, ironic. The winds of change have backed round and blow from another quarter. Having freed Africans from the bonds of servitude, Western liberals promoted a brief vision of a homegrown Utopia. And now Africans are leaving in rotten boats for another Utopia, glimpsed on smartphones. If they make it to France, their overwhelming desire is not to claim asylum there but to reach their El Dorado, England. It is the single aim that the warring packs of Somalis, Eritreans, and Ethiopians have in common, and in England they can join their fellow tribalists. Currently, they have been moved on from their preferred channel port in Normandy, Calais, and now congregate in Ouistreham for their daily attempts to board England-bound trucks. Ouistreham was better known in 1944 as Gold Beach, site of the D-Day landings by British and Canadian forces. The symbolism writes itself. As for the liberalism of The Economist, which does indeed need to be “renewed,” Matthew Arnold said it best:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full . . .

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar . . .

Leave a Reply