It was now the beginning of the seventh year of the genocidal invasion of Afghanistan. To many Americans it appeared that the war would never end, not until the entire population of Afghanistan was either dead or in exile. Some Americans thought it was time to do something about Soviet imperialism, especially since a good many of them had spent the entire summer and fall picketing the South African Embassy in Washington, daring arrest, while others were denouncing President Reagan’s “Star Wars” and the U.S. invasion of Grenada. Much earlier, they had been in the forefront of protest against the war in Vietnam. Obviously something had to be done to balance the equation; people might criticize their moral credentials. After all, they had been cheering for a long time Bishop Tutu and Nelson Mandela but never a word about Andrei Sakharov or Anatoli Shcharansky.

And so we saw on a cold, raw February afternoon, a march on the Soviet Embassy. It was headed by Richard Barnet and Mort Halperin of the Institute for Policy Studies. They were followed by William Kunstler, the people’s attorney; Anthony Lewis and Tom Wicker of The New York Times, Richard Cohen of the Washington Post; Senators Christopher Dodd, Lowell Weicker, and Alan Cranston; Alexander Cockburn, the columnist; Victor Navasky of The Nation; the Rev. William Sloane Coffin and the Brothers Berrigan; Mrs. Bella Abzug; Professor Bertell Oilman, the New York University Marxist; Harvard History Professor John Womack and Harvard Law School Professor Duncan Kennedy. From overseas came Arthur Scargill, the British miners’ boss; Günter Grass, the German writer, accompanied by Willy Brandt; Jack Lang and Regis Debray, President Mitterrand’s favorite leftists. They, too, were concerned about their moral credentials and wanted to show the world that they supported the American left’s desire to dispel the unfortunate impression that “moral equivalence” was really a double standard.

When the protest march reached the Soviet Embassy, it stopped on the sidewalk outside to regroup while a delegation comprising Speaker Tip O’Neill, Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Mary McGrory, Armand Hammer, and Ed Asner were invited in for tea and zakuski, those nice Russian hors d’oeuvres. Ambassador Dobrynin received them in person and listened with grave courtesy to their protest at the Soviet action in Afghanistan.

“Many of us, indeed almost all,” began Ms. Fonda, “were wholly opposed to the American action in Vietnam and took various measures to express our view of the matter, even to committing what some reactionaries called treason. We believed that our country was quite unjustified in sending troops to intervene in a quarrel that was no concern of ours. Even if the government was right in principle, the suffering caused by our action was wholly out of proportion to any good it seemed likely to do. And we felt the same way about the invasion of Grenada.”

Ambassador Dobrynin nodded. “Go on,” he said pleasantly, “but please explain how this analogy fits your protest against my country’s support of the liberation movement in Afghanistan.”

“Why, don’t you see,” said Ms. McGrory peevishly. “Surely you can understand how we, never motivated during the Vietnam War, and later during the Grenada invasion, by anything but a burning sense of injustice at the action of a mighty military power against a small nation’s struggle for independence and freedom, would be regarded—as a matter of fact, rightly—by ourselves as well as others, as no better than so many hypocrites if we remained silent for almost seven years in the face of another action by another mighty military power against another small nation.”

That same evening all three networks, who had broadcast all kinds of documentary and news programs against South Africa, did a combined program in which Harrison Salisbury, introduced as an expert on Afghanistan “with no political axe to grind,” described the Soviet aggression in Afghanistan in language as objective as he had used in describing the U.S. bombings of North Vietnam. To balance the program, the three networks engaged Dan Rather, Walter Cronkite, Peter Jennings, and Tom Brokaw, all of whom agreed with Salisbury.

President Carter, who, it will be recalled, lost faith in the Soviet Union after its attack on Afghanistan, made a special appearance. He said that he was now convinced that the American people were absolutely right in having an inordinate fear of Communism. With a thrust at President Reagan, he added that, had he been reelected in 1980, there would now be American—not Soviet—troops in Afghanistan. Mrs. Carter chimed in, saying she would have used laser and particle beam and other kinetic energy weapons. Mr. Carter agreed.

As was only to be expected, a substantial number of groups have sprung up spontaneously designed to achieve the widest possible variety of world protest against the Soviet action. None of these, of course, have any connection with any other group; indeed, few are even aware of the existence of the others. (The fact that they all operate from the same New York address is purely coincidence.) These groups include the Committee for Peace in Central Asia, the Peace in Central Asia Committee, and the Afghanistan Committee for Peace. There are also Doctors Against Soviet Imperialism, Teachers Against Soviet Imperialism, Journalists Against Soviet Imperialism, Hollywood Against Soviet Imperialism, Labor Against Soviet Imperialism, Intellectuals Against Yellow Rain in Afghanistan, and Anti- Intellectuals Against Bee Feces in Afghanistan.

The Black Caucus in Congress has been so aroused over this attack on a Third World country that its leadership has proposed resolutions defining the attack on Afghanistan as “racist” and demanding that President Reagan send all possible military aid including tactical nuclear weapons to help the beleaguered Afghan people unless he, too, wants to be regarded as a racist. A Congressional delegation headed by Rep. William Gray demanded the right to visit Afghanistan as they had South Africa so that they could see the real situation for themselves. If the USSR failed to grant such permission. Rep. Gray, with the full support of the Black Caucus, was prepared to call for an end to all trade and cultural relations with Moscow.

In Tunisia, Yasir Arafat was so indignant at what the Russians were doing to a Moslem country that he set up an Inter-Arab Committee Against Soviet Imperialism with the Kings of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, Muammar Qaddafi of Libya, and President Assad of Syria as honorary chairmen. In Canada, former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau organized the interparty Canadian Trilateral Commission Against Soviet Aggression Anywhere and Everywhere. Ingbar Carlsson, the Swedish Premier, was so indignant that he sponsored the Scandinavian Committee Against Soviet Aggression Anywhere and Everywhere. Professor George Kennan wrote an article from a historical perspective in which he said that the Russians under Mikhail Gorbachev were worse than the Prussians under Bismarck. The article was reprinted on the front page of the Washington Post.

But it is in the Soviet Union itself that the biggest volume of public protest is to be found. Most impressive is what happened when the Soviet Committee for an End to Soviet Involvement in Afghanistan held an all-night vigil outside the Kremlin walls. At one point during the frigid night, the KGB guards appeared with cans of hot soup which they distributed to the invigilators. Through it all, Gorbachev lived up to Seweryn Bialer’s praise for him in The New York Times as a man “open to new ideas.” At about one o’clock in the morning, Mr. Gorbachev emerged from the Kremlin wearing an overcoat and fur hat. Even though a heavy snow was falling, he moved among the crowds of protesters quite freely, talking to them, listening to their views, and assuring them that although he disagreed with what they said, he would fight to the death for their right to say it.

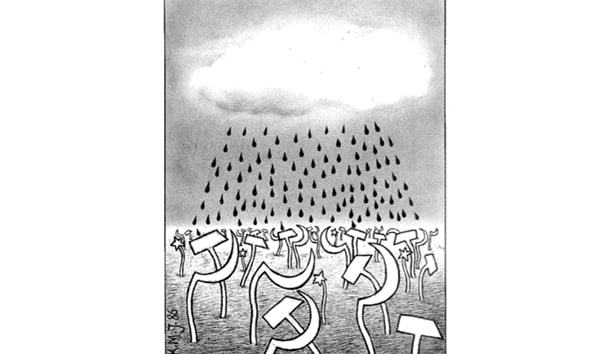

Editor’s Note: Owing to technical errors beyond anyone’s control, the word “not” was unfortunately omitted throughout the article above.

Leave a Reply