“Exsilioque domos et dulcia limina mutant,

Atque alio patriam quaerunt sub sole iacentem.”

—Virgil, Georgics II.511-12

Honestly, why bother any more? If there is any unifying theme in the scribblings of genuine, bona-fide American conservatives, it is that our country is lost, whether to whoremongers or warmongers—or both. Drum sets in the chancel, and fairies in the pulpit. Good jobs shipped to Mexico and China, and semi-loads of cheap Chinese goods and unassimilating Mexicans shipped here. Grown-ups who know how to read but won’t, and children taught to solve math problems by drawing pictures. Republicans and Democrats dropping bombs on the Middle East, and Democrats and Republicans blowing up the definition of marriage. An upcoming election that will be, in its literal meaning, a zombie apocalypse. And it seems there is little or nothing we can do to change any of it.

These are real and significant concerns, and while it pains me to say it, I think we would be better off ignoring them for just a moment, along with the news in general, to ponder the utterly esoteric and impertinent meaning of a 77-year-old essay on Yankees and Rebels, as well as the very narrow but practical question of what to do with the graves.

He had moved in the 50’s, his late 20’s, from the Arkansas Delta, where rice and cotton fields stretched wide beneath Crowley’s Ridge, to Northern Illinois, where acres sown with corn and beans were interrupted by river towns and cities dotted with coal- and cash-belching factories.

The occasion of the move was poverty. There was no money in sharecropping, and working a rice-dryer by day and driving a cab in West Memphis by night gave little time for his muscles and mind to recover. Life was passing by. He couldn’t provide for his wife and little daughter. His house was a shotgun shack.

Thus, he found himself, his wife, and his child in a foreign country. But not all of his family: Dad, Mom, brothers, sister, aunts, uncles, and cousins all stayed in the fatherland. His wife’s side had, for the most part, emigrated already—most of them were in-country, and a few more were on their way. He’d live in a two-story house with a basement and some in-laws, and walk into one of those factories on the river, three blocks from that two-story house, and get a job.

He didn’t live in the lap of luxury, but grinding poverty was now a thing of the past. So were Friday Night Fights on the family TV at his parents’ house, fishing the familiar and unsullied streams of the Delta, hunting ducks with his brothers, watching his daughter make peach pies with his mother. He was drawn to new friends at the plant, most of them fellow immigrants with similar accents, but they didn’t hear the same news from home or know the same people. They were similar, and formed a community around the similarities. Together, they were now Southerners, formerly poor, known for their mannerisms, their pickups, their Democratic ballots, their inherited religion (sometimes Baptist, sometimes Church of Christ). Fridays, the Yankees—Johnsons and Gustafsons and Ericksons—left the plant, put on aftershave, and headed to the parish fish fry; the Southerners went home to catfish and hush puppies. Saturday evenings, the cultural divide was marked by Lawrence Welk, broadcast from Los Angeles on ABC, versus the National Barn Dance, from Chicago on WLS, and the Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville on WSM and NBC.

To the natives, he and his friends were Sons of the South, living in the Land of Lincoln. But they’d been raised as Americans, lied about their age (if need be), and gone off to war to escape, if just for a few months, the prison of sharecropping. Home was a short drive to kin, not the Land of Opportunity and Orval Faubus. There was no shame in the memory of their country’s past, which had been destroyed and reconstructed long before they were born; they focused on the present—first, second, or third shift, overtime, and summer vacation.

His two weeks in the fatherland every summer began with joy and ended in melancholy. Your girl is getting so old, they’d say. Dad and Mom are getting so old, he’d think. Where is home? Why did I leave? When will I return for good? Everything about his Northern home seemed increasingly foreign whenever he stepped on his native soil. Then came the news: His oldest brother had died suddenly. The only thing he could do was call the foreman, pack up his wife and his daughter, and drive all night. He’d be back to work at 7 o’clock on Monday morning.

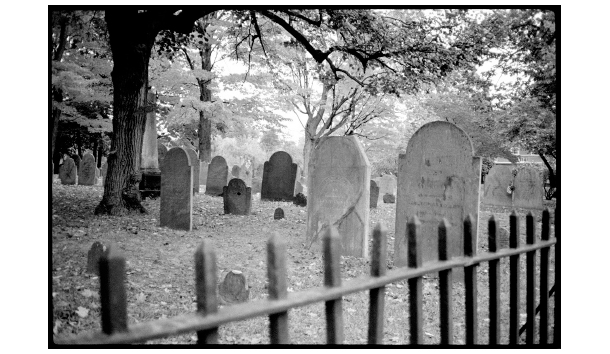

Standing there in the cemetery, he made up his mind: One day, at last, I will come back. His surety came in the form of two graves, a stone’s throw from the plots owned by his parents—one for himself, and one for his wife. With extra money he’d earned plowing snow at that factory on the river, he made a cash down payment.

Seeing the title “Still Yankees, Still Rebels” affixed to a 1938 essay by the Southern Agrarian Donald Davidson might lead the virgin reader to assume that its contents will include Sherman’s march to the sea set forth as a simile for FDR’s New Deal, and a call to arms beckoning Southerners to march behind the Battle Flag to the gates of Boston. In this instance, however, the poet takes up his pen to give the lie to the statistically proved theorems of social scientists, which assure us that the uniformity of American culture is a worthy goal and nearly reached. Contrary to the sacred visions of progressive sages, he writes, America remains a country of real peoples, “incarnations of the principle of diversity through which the United States have become something better than Balkan, and without which the phrase ‘my country’ is but a sorry and almost meaningless abstraction.”

The War Between the States had been won by the side that united behind Lincoln’s vision that so vast a country, then the size of Western Europe, must “become all one thing, or all the other.” Having unleashed rivers of blood, he achieved that politically. But culturally, he did not. And despite the postwar leveling efforts of Washington and Manhattan, there were still Yankees and Rebels, living well, felix et fortunatus, across the fruited plain.

Davidson gives reasons, which point us back to the land—both its natural features and the people who are vitally connected to it. This was, of course, another iteration of the Agrarian vision, set forth memorably in I’ll Take My Stand, which Davidson organized to defend the South against industrialism, the capitalist commodification of the land, and communism. But “Still Yankees” was a paean not (just) to the South, but to America, where “there are unreconstructed Yankees, too, and other unreconstructed Americans of all imaginable sorts, everywhere engaged in preserving their local originality and independence.”

To prove his thesis, Davidson invites us to look closely at the real people who live outside of the dreams of sociologists, for, “if anything positive is to be done, it must surely be through a laborious process of discovering America all over again,” where the contours of the land shape the people, and the people, in turn, shape the contours of the land. And, because reality is best ascertained not by statistics or polls but by stories, he tells a couple of them.

The first is about “Brother Jonathan,” who lives in Yankeetown, Vermont. Brother Jonathan works his ancestral 200-acre farm with East Anglian devotion, and draws deep satisfaction from his labors. Generations of his people have carefully manicured the fields, woods, and meadows, and the earth, despite the brutality of Vermont winters and a short summer, bringeth forth his fruit in his season. That is in no small part because, while 70 years old, he works long and hard daily to subdue the earth and enjoy the fruits of his labors.

Brother Jonathan’s devotions extent to his family and neighbors, around which life revolves—Sophronia, his wife; his son, Nathaniel, who is building a house; Priscilla, Nathaniel’s wife. There are regular conversations over New England boiled dinner, conversations about the town doings, politics, tales of the past with “a dry quip or two by way of garnishment.” Greater times of celebration might include “a corn-roast, with a few cronies and kinfolks from the village,” where more of the same conversation will be extended.

The second involves “Cousin Roderick of Rebelville,” Georgia. Roderick has reached a stage of life at which he now manages what is left of the family plantation, making the rounds in his Chevy and seeing that all of his crops and employees are cared for. There is, of course, a cash crop of cotton, but Cousin Roderick aims, and for the most part succeeds, at feeding his large family with the vegetables, fruits, and nuts his workers harvest from the ancestral lands.

Cousin Roderick would appear to a Yankee as shiftless, but his way of life is a semiconscious effort at cultivating leisure—a “philosophical defense against the dangerous surprises that life may turn up.” His life is shaped by his interactions with his community who are, for the most part, relations. Sister Caroline, young Cousin Hector, Aunt Cecily, Uncle Burke—“Before supper, or after, some of the kinfolks may drop in, for there is always a vast deal of coming and going and dropping in at Cousin Roderick’s.”

Through narrative based on his own experiences (including many summers in Vermont), Davidson underscores the beauties of the two societies, still thriving and shaping meaningful lives. Their differences are noted, demonstrating the happy Balkanization that still obtains (or, at least, obtained in 1938) in American life, a witness to the failure of the cultural levelers.

Nonetheless, readers of Davidson’s essay today are left with a painful reality: Brother Jonathan and Cousin Roderick are gone. So are Yankeetown and Rebelville, and with them most of the stable American societies and cultures that gave meaning and happiness to American life. That was true, or nearly true, when “Still Yankees, Still Rebels” was anthologized in 1957 in a book by the same name.

A fair amount of cultural revolution has happened since then, much of it predicted by the Agrarians, Eliot, Orwell, and Huxley, among others. We tend to see what is obvious: the immigration crisis, gay marriage, abortion on demand, endless push-button wars, runaway debt, joblessness.

These are symptoms—symptoms of a society that lives in defiance of the natural order, not to mention the God Who created it.

Man was made to be in the soil. This is perhaps more obvious to someone who takes the Pentateuch seriously (Adam, which means “of the clay,” was made from it), but even the most stubbornly Darwinist social scientist must admit that human flourishing in something called civilization occurs historically when crops are sown. Growing food is essential to physical life but also to social sanity, as it galvanizes communities who depend on the land, nature, and nature’s God together. It is also necessary to political life, at least in the system drawn up by the Founding Fathers and drawn from the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Agriculture means independence. That was Mr. Jefferson’s vision, and it was not limited to the South, in either theory or reality. The North may have been dominated politically by industry and an inclination toward internal improvements, but when the War started, the land was covered by small family farms from Vermont to Georgia, Arkansas to Illinois.

The Jeffersonian theory was the reality in which both Brother Jonathan and Cousin Roderick lived, the basis for the economies of Rebelville and Yankeetown. Agribusiness has since plowed over those farms, towns, and villages, turning them into factory farms, bedroom communities, and suburbs. We cannot snap our fingers and make Big Ag disappear, for reasons known to many and best explained elsewhere. But there is another aspect of life in harmony with the natural order, shared by Davidson’s Yankee and Rebel, which gave life to their communities and shape to their happiness. Something else we have lost.

Families no longer stay together. By this I don’t refer simply to the devastation of divorce or the distractions of frenetic schedules or the “necessity” of two-parent incomes. These problems belong to the nuclear family, and they, too, are symptomatic. I’m speaking of Davidson’s “kinfolks from the village,” of (adult) Sister Caroline, Cousin Hector, Aunt Cecily, Uncle Burke. True, our globalist economy has devastated the American job market, causing grown children to struggle to find hometown employment. But we had already believed the lie of upward mobility and “going places,” regardless. Each generation, if it is to be counted successful, must go far away to college, and even farther to find the job that the college degree entitles it to work. Often, we live wherever the whim blows us.

Fractured American society does not value life that is lived in regular communion with fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. This is disordered and contrary to nature. Blood-relatives are naturally inclined toward one another. They are the best business partners and babysitters, counselors and mentors. Family loyalty is strengthened by large households and breeds honor and accountability, including marital fidelity. It restrains hubris. It provides for a common defense. It promotes a general welfare. The theme runs through the Bible, Homer, Virgil, and Shakespeare.

In another essay (“Why the Modern South Has a Great Literature”), Davidson writes that

A traditional society is a society that is stable, religious, more rural that urban, and politically conservative. Family, blood-kinship, clanship, folk-ways, custom, community, in such a society, supply the needs that in a non-traditional or progressive society are supplied at great cost by artificial devices like training schools and government agencies.

For this to be so, families must not simply exist, but their members must live in relatively close proximity. That in America they don’t is often simply a matter of choice, or a series of choices. China has a one-child policy; we freely choose it. We blame a socialist government for wresting from us the rearing of children and the care of the elderly and disabled, yet we willfully abandon the natural condition in which these responsibilities are most easily fulfilled.

Conservatives today speak a great deal about the evils of big, centralized government, about the need to restore our republican polity. Yet very few are quick to point out that every (relatively brief) historical instance of a successful republic has had, among its features, clans made up of families living in community. The democratic tyranny of the majority in which we now live is made possible by the breakup of such communities of shared traits and interests, of preexisting natural loyalties that foster self-sacrifice and wealth sharing, and extend beyond politics and political party.

Atomized Americans, like Western Europeans, feel the natural pull toward family identity, but living in isolation from those with whom we share blood and inherited custom, we turn our inclination toward kinship into an abstraction, and our commitment to that abstraction turns our hearts away from the responsibilities that make flourishing and happiness possible. “Why can’t white people be proud of their race?” asks many a frustrated conservative, though most often in private. The answer is that white people didn’t raise you, don’t live with you, don’t look with affection at pictures of your children, don’t visit you in the hospital, and won’t pay for your funeral. Your family does that. To argue that race is something more than an extension of the family and clan, and that our flourishing depends on our recovery of “racial consciousness,” is to turn nature on its head; it is the boldest hypocrisy to share the credit for the achievements of “white Europeans” when we deny responsibility (whether overtly or through indifference) for those with whom we share ties of blood and daily life.

And yet, right now, we are free. We are free to stop making the choices that lead to the separation of kinfolk, and all of the losses that go with it. Conservatives who are rightfully concerned about the illegal immigrants flooding over our borders and the threat they pose—ethnically, economically, politically—to traditional American culture and life would do well to imitate them. Not in breaking the law, but in seeing the family as something larger than two parents and one-and-a-half children; or even 19 children. There are great sacrifices that must accompany such a commitment, but there are also great rewards: most importantly the thing itself, which is its own reward. There are many threats to our traditions, our freedoms, our faith—the cultural realities that once distinguished Yankees and Rebels—but we will not be in any position to address them effectively until we submit to the natural order by living among our own people as much as we are able.

Granny was dying, and well outside her hearing, plans were beginning to be discussed. There was one topic no one wanted to bring up. It was painful, but the subject had to be broached. “If we bury her in Jonesboro, we won’t get to visit y’all’s grave very often,” we said.

The pain of the immediate circumstance gave way to cruel reality. His people—Dad, Mom, brothers, sister—were gone, and the nieces and nephews were scattered to the four winds. But his mourning, their slow death in his imagination, had begun half a century ago. Ties to the land were cut because the family no longer lived on it. All of those who would bring flowers and say prayers lived here, including, for the time being, himself.

He was growing increasingly frail, and seemed to know he would decline even faster after she’d breathed her last. And so Gramp withdrew some money from the factory credit union and paid cash for two plots in Yankeeland.

Months after Granny’s funeral, we asked him what to do with the other graves.

“Sell ’em,” he said. “When I’m gone.”

Leave a Reply