From the October 1992 issue of Chronicles.

Probably not since Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind has a popular novel influenced Americans as deeply as Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. Appearing in 1969, the book remains, according to the inflated come-on of its publisher’s blurb, “the all-time best-selling novel in publishing history.” If true, that claim in itself is no mean accomplishment, considering that Mr. Puzo’s competitors have included such deep-pocketed wonderboys of the book trade as Stephen King, Harold Robbins, and the late Isaac Asimov.

Yet the permeation of pop culture by The Godfather is not measured by its publishers’ ledgers. The novel has given its name to a national pizza chain, suggesting that even the teenagers who habitually consume pasta for the masses still readily recognize the literary allusion; and twenty years after the release of the first of Francis Ford Coppola’s three movies based on it, the book’s major characters and events remain familiar to millions of Americans. Moreover, the book and films excited mass interest in the subject of organized crime in the United States and spawned entire new shelves of reading, fiction and nonfiction, as well as inevitable and innumerable cinematic spin-offs, almost all of which are thin reruns of the novel’s distinctive characterization of criminal intrigue as delicate family matters. The novel and films contributed to American colloquialism almost as much as the Watergate scandal, which was contemporaneous with the first two movies. Even today, expressions such as “an offer he can’t refuse” and “sleeping with the fishes” remain current, and common words such as “godfather” and “don” acquired new and enduring meanings from The Godfather cycle. Coppola and Puzo together have turned out almost as many movies based on the epic of la famiglia Corleone as there have been trials for John Gotti, though with the third installment released in 1990 and its final liquidation of the dwindling band of characters who had not been shot, eviscerated, blown up, or garroted in the first two films, it is hard to see how even Hollywood can come up with any more.

Long dismissed as a cheap glamorization of organized crime, a 450-page sex-and-violence wallow in the pigpen of mass culture. The Godfather has nevertheless evolved into no less a classic than Gone With the Wind itself, though it would be idle to pretend that Puzo’s contribution to literature ranks with the work of the more serious novelists in the American canon. The book is dependent on sensationalism, with graphic depictions of bedroom tussles and physical brutality and a reliance on the improbable that always attends low fiction. Nevertheless, there are in both the novel and in at least the first two Godfather movies consistent, disturbing, and powerfully presented themes that deserve closer inspection than the literary merits of the book suggest. Read or viewed not simply as thrillers for beach and boudoir but as an extended metaphor of American and perhaps of human society, the novel and Parts I and II of the film series rip the mask off certain mythologies of America and modernity and offer perceptions that may reveal truths that no grand jury and no congressional subpoena has uncovered as successfully or dramatically.

“Crime,” wrote Daniel Bell, “in many ways, is a Coney Island mirror, caricaturing the morals and manners of a society.” Just as anthropologists glimpse in the cultures of primitive peoples persistent truths of human nature and society obscured by the more complicated institutions of modern life, so the brutally simple relationships among criminals expose and highlight similar patterns on which all human social and political institutions rest. The bloody antics of mafiosi and their molls may amuse, titillate, and horrify the readers of the tabloid press, and Puzo’s novel, to be sure, lends them a dignity that in real life they neither possess nor ought to acquire. But far from merely romanticizing and whitewashing organized crime in America, The Godfather uses it as the center of a symbolic complex of primal patterns out of which modern Western society grows and from recognition of which the characteristic superstitions of modernity usually flee.

“Behind every great fortune there is a crime,” wrote Honore de Balzac in a cynical sentiment that Puzo chose as the epigraph of his novel. The line at once establishes the metaphor that dominates the book as well as the films and carries us into the essentially Machiavellian world view that pervades them and to which most of its Italian-American characters subscribe. If “great fortunes” may be read as “human society” itself, then the history of crime becomes the history of society. The Godfather thus begins with not merely an analogy between the warfare and power struggles among criminals on the one hand, and the more normal civil relationships of legitimate society on the other, but also with an actual genealogy that traces the latter to their origins in force and fraud.

Nor is the line from Balzac the only way the crime-society metaphor is established. Throughout the book and films, there is a continuous flow of language and event that suggests the analogy, and the characters themselves frequently invoke it. When Tom Hagen, consigliore to Don Vito Corleone, urges his boss and foster parent to accept the offer of a partnership with the Sicilian gangster Sollozzo for peddling drugs, he cites the power practices among real governments. If the Corleone family doesn’t accept Sollozzo’s bargain, Hagen argues, it will eventually be overwhelmed by the rival families. “It’s just like countries,” he says. “If they arm, we have to arm. If they become stronger economically, they become a threat to us.” The capo regime Clemenza, explaining to Michael Corleone why a gang war is necessary, draws his own analogy with pre-World War II diplomacy, in a scene from both book and film. “These things have to happen every ten years or so,” muses the corpulent killer. “You gotta stop them at the beginning. Like they shoulda stopped Hitler at Munich, they never should have let him get away with that, they were just asking for big trouble when they let him get away with that.”

Yet the clearest such analogy between criminal and legitimate society is voiced by Michael Corleone himself in Part I of the film series. Explaining to his innocent fiancee Kay Adams why the work of his father, one of the most powerful gangsters in the country, is not as sinister as it seems, Michael tells her, “My father is no different than any other powerful man—any man who’s responsible for other people, like a senator or a President.” It is a comparison that Kay, daughter of a Baptist clergyman from New Hampshire, at once rejects. “Do you know how naive you sound?” she asks in the naively preachy way such women affect. “Senators and Presidents don’t have men killed”—a line that, when the movie is shown in crowded American theaters, never fails to collapse the audience into derisive laughter. Whatever the veracity of the crime-society metaphor, apparently a lot of Americans, at least in the Watergate era, were perfectly comfortable with the notion that it was true.

If the premise of the novel is that the practices of normal or legitimate human society are analogous to those of criminal gangs, it is hardly surprising that the ghost of Machiavelli lurks throughout the novel and films, since the view of political power as essentially extralegal and extramoral is a fundamental theme of Machiavelli’s political thought. Though his name is never invoked, there are clear instances of what may well be the direct influence of the Italian political theorist whose name has become (unjustly) synonymous with the synthesis of cunning and brutality. As in Machiavelli’s thought, the Prince is not only above the law but the source of law and all social and political order, so in the Corleone universe, the Don is “responsible” for his family, a responsibility that authorizes him to do virtually anything except violate the obligations of the family bond. Michael’s description of his father is not only Machiavellian but also virtually Nietzschean. “My father,” Michael tells Kay,

is a businessman trying to provide for his wife and children and those friends he might need someday in a time of trouble. He doesn’t accept the rules of the society we live in because those rules would have condemned him to a life not suitable to a man like himself, a man of extraordinary force and character. What you have to understand is that he considers himself the equal of all those great men like Presidents and Prime Ministers and Supreme Court Justices and Governors of the States. He refuses to live by rules set up by others, rules which condemn him to a defeated life. But his ultimate aim is to enter that society with a certain power since society doesn’t really protect its members who do not have their own individual power. In the meantime, he operates on a code of ethics he considers far superior to the legal structures of society.

Moreover, Don Corieone’s conversation as well as that of Michael and the other mafiosi is full of such homespun amoralisms of power-playing as Machiavelli would have treasured: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer”; “Revenge is a dish that tastes best when it is cold”; “a lawyer with his briefcase can steal more than a hundred men with guns”; and so on. They are just the sort of adages that fill the pages of Machiavelli’s own works, and they are based on his assumption, which he shares with the Corleone family, that human nature does not change and therefore the natural laws by which human beings gain, use, and lose power remain permanent as well. And not only permanent but universal, so that they apply to the dynamics of Mafia intrigues as much as to the relationships among governments and between governors and governed.

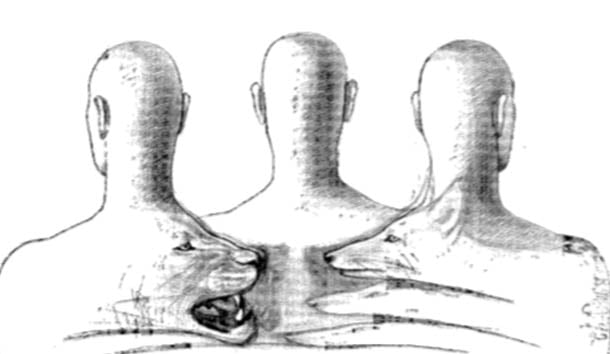

A prince, Machiavelli advises, must know how to imitate the lion and the fox, to use both force and cunning effectively, though it is also clear that most rulers do not know how to do so and rely on one or the other too much. The lion-fox polarity, one of Machiavelli’s best known laws of power, is rather clearly manifested in the scene in the novel and Part I of the film series where Don Corieone’s sons, Santino and Tom Hagen, argue over how to respond to the attempted assassination of the Don and the attack on their family. Santino, a headstrong and violent young man, is eager to “go to the mattresses” in an all-out war with the rival gangs who back his father’s enemy Sollozzo. Notorious even in Mafia circles for his hot temper and taste for violence, Santino is the lion, and indeed the name “Corleone” can be translated as “Lionheart.” Hagen, an adopted son of The Godfather, is not Sicilian but German-Irish; he counsels prudence and further negotiations. If Santino is the lion, Hagen is the fox, and the conflict between them appears to be a stalemate.

It is then that Michael, the Don’s youngest son, who was not raised to take part in the family’s criminal affairs, injects himself for the first time into “family business.” His plan is simple. Sollozzo won’t suspect Michael, precisely because Michael has nothing to do with the family’s activities. Michael proposes to accept Sollozzo’s offer of a meeting on neutral ground for the ostensible purpose of negotiating, but Michael will smuggle a gun into the meeting and kill Sollozzo, It is a plan that combines the cunning of the fox and the violence of the lion, transcending the polarity that divides and debilitates Santino and Hagen, revealing Michael as the ideal Machiavellian prince, and initiating him into the course that will bring him to power as his father’s avenger and successor.

Similarly, the role of religion in the novel and particularly in the films also illustrates Machiavellian themes. Religion for Puzo and Coppola appears to have two applications: as a mask behind which criminality hides and as a sop for women, children, and unmanly men. The irony of the title of “Godfather” itself points to the former use, as does the powerful climactic scene in Part I when Michael, literally becoming godfather to the child of his treacherous brother-in-law through the sacrament of baptism, renounces Satan and all his works while at the same moment his assassins cut down his enemies, making him the new Godfather on another level of meaning.

The use of religion as a Machiavellian mask is continued and intensified in Part II, where the repulsive Don Fannucci of the Black Hand ostentatiously offers a large cash donation to the Catholic Church and deplores the violence of a Punch and Judy show, even as the young Vito Corleone stalks him during a religious festival in the streets, using the celebration of the Mass as a distraction to kill Fannucci and initiate his own rise to power. Indeed, throughout both films there is not one religious ceremony or its social celebration that does not serve as a mask for crime: the wedding reception sequence that opens Part I, during which Don Corleone plans crimes on behalf of his retainers; the baptism scene at the end of the film as well as the funeral of Don Corleone, when the late Don’s capo regime Tessio betrays Michael; the confirmation of Michael’s own son in Nevada at the beginning of Part II; and the funeral of Michael’s mother toward the end of Part II, when Michael gives the order for the murder of his brother Fredo. This pattern is generally evident in the book as well, and in describing the grand meeting of the heads of the nation’s crime families in the book, Puzo tells us with irony that “it must be noted that some of these men were religious and believed in God.”

Indeed, the only grown man in either the book or the films who takes religion at all seriously is Fredo himself, who, as Michael describes him, is “weak and stupid.” Just before his own assassination in Part II, Fredo plans a fishing trip with Michael’s son, and Fredo assures the boy that the way to catch a fish is to say a Hail Mary when he drops the line in the water. As Fredo sits in the boat repeating his prayers, Michael’s gunman blows his brains out from behind.

The Godfather‘s general use of religion is virtually identical to the advice offered by Machiavelli to the Prince that “it is well to seem merciful, faithful, humane, sincere, religious, and also to be so; but you must have the mind so disposed that when it is needful to be otherwise you may be able to change to the opposite qualities,” his belief, based on his reading of Roman religion, that “everything that tends to favor religion (even though it were believed to be false) should be received and availed of to strengthen it,” and the saying of Cosmo de Medici, quoted by Machiavelli in his History of Florence, that “it required something more to direct a government than to play with a string of [rosary] beads.” Rome itself occasionally is invoked in both book and films, as when Michael notes that Santino is scribbling down the names of men to be killed “as if he were some newly crowned Roman emperor.”

Yet while the book proceeds from the premise that legitimate society and criminal gangs are analogous, it is at once evident that there is also a difference between them. In the course of his daughter’s wedding reception, Don Corleone has the duty of meeting with and granting favors to many friends and relatives. The first of the men to approach him is an undertaker, Amerigo Bonasera, who tearfully complains that his daughter has been attacked. Bonasera is an immigrant and has tried all his life to be a good American, as his first name implies. He has obeyed the law and raised his daughter as a respectable young woman. Recently, she dated a young man, the son of a U.S. Senator, who tried to seduce her. When she rejected his advances, her date and a friend beat her savagely, sending her to the hospital and permanently disfiguring her features.

Being a good American, Bonasera went to the police and brought charges against his daughter’s assailants. The scoundrels were convicted. But because of their fathers’ political influence, the judge gave them only a suspended sentence, and they smirked at Bonasera as they left the courtroom. Now he comes to Don Corleone.

The Don’s response conveys the principal expression of the moral code of the book and, even more, the films. Bonasera is not a friend of the Don. In all the years they have known each other, Bonasera avoided his company, never invited him to his house, never did him a favor or asked a favor of him. That’s all right with the Don, but now, all of a sudden, Bonasera comes to him and asks him, in return for money, to commit murder. The Don refuses, his dignity wounded by Bonasera’s tasteless insult.

Bonasera wanted to be an American, and he turned his back on his cultural heritage and his natural friends. “America,” he moans, “has been good to me. I wanted to be a good citizen. I wanted my child to be American.” And, of course, he wanted American justice, which is exactly what he got. “You never armed yourself with true friends,” the Don tells him. “After all, the police guarded you, there were courts of law, you and yours could come to no harm. You did not need Don Corleone.” But now, when the fake, purchased justice of America has failed him, to whom does he turn? Don Corleone’s sarcastic advice is that Bonasera accept the judgment of the American court and give up his idea of revenge. “The judge has ruled. America has ruled,” he says. The notion of vengeance for a wrong suffered by a family member is “not American.” Best for Amerigo Bonasera to give it up.

America, as the Don describes it and as Bonasera has experienced it, does not behave like the Corleone family after all, and the differences between the two societies do not favor America. The differences between the two are precisely those between two kinds of social organization that sociologists describe as Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft respectively. Gemeinschaft refers to a kind of culture characteristic of primitive, agrarian, tribal societies, in which bonds of kinship, blood relationship, feudal ties, social hierarchy, deference, honor, and friendship are the norm. “The three pillars of Gemeinschaft—blood, place (land), and mind, or kinship, neighborhood, and friendship—are all encompassed in the family,” wrote the German sociologist Ferdinand Tonnies, who first used this terminology, “but the first of them is the constituting element of it. . . . The prototype of the association in Gemeinschaft remains the relationship between master and servant or, better, between master and disciple.” Tonnies saw the Gemeinschaft pattern as dominant in the European Middle Ages but as slowly disappearing before the revolutionary changes brought about by the rise of the Gesellschaft pattern in the process of modernization.

“Conversely” to Gemeinschaft, writes Robert Nisbet, “Gesellschaft . . . reflects the modernization of European society. … In pure Gesellschaft, which for Tonnies is symbolized by the modern economic enterprise and the network of legal and moral relations in which it resides, we move to association that is no longer cast in the mold of either kinship or friendship. . . . The essence of Gesellschaft is rationality and calculation,” an essence expressed in such modern organizations as corporations (for which Gesellschaft is the German word) and the formal, impersonal, legalistic, bureaucratic organization of the modern state.

It is a principal thesis of The Godfather that American society is a Gesellschaft at war with the Gemeinschaft inherent in the extended families of organized crime, and it is the claim of the novel and even more intensely of the films that the truly natural, legitimate, normal, and healthy type of society is that of the gangs. It is a claim buttressed by the savage depictions not only of the corrupt justice offered by America to Bonasera but also of virtually every character in both book and films who is not Sicilian and therefore is not part of the criminal Gemeinschaft: Kay Adams herself, the liberal WASP college girl who has no conception of the brutal forces that lie under and around her small social island; Jack Woltz, the vulgar and sex-obsessed Hollywood producer; Captain McCluskey, the crooked Irish cop who is in the pay of Sollozzo; Moe Greene, the Las Vegas gangster based on Bugsy Siegel; and in Part II of the film series, Nevada Senator Pat Geary and Hyman Roth, a fictionalized version of the late Meyer Lansky. Roth indeed is the most articulate and attractive of these representatives of the American Gesellschaft, and except for Kay, who is merely a child, most of them share certain characteristics. All of them are motivated mainly by avarice, and the cash bond is the only one they acknowledge or understand. Most also lack self-control; they lose their tempers unnecessarily and insult and try to cheat men with whom they want to do business, and some are slaves to sexual lusts that the prudish Don Corleone considers infamia. Lacking the natural bonds of Gemeinschaft through strong family attachments, the characters who represent Gesellschaft are bound only by their personal appetites, and it is through their appetites—greed, anger, lust, obsession with revenge served not cold but piping hot—that they usually meet destruction.

By contrast, the Gemeinschaft of the Corleone family is embodied in Don Corleone himself, well-known for his humility, his caution, and his devotion to family. “A man who never spends time with his family can never be a real man,” he tells his godson, Johnny Fontane, who has been unmanned by Hollywood Gesellschaft, but the remark is really addressed to his real son Santino, who is preoccupied with sex. “Even the King of Italy didn’t dare to meddle with the relationship of husband and wife,” the Don tells his own daughter when she complains that her husband is beating her. Outside the bond of family and friendship, outside the Gemeinschaft, Don Corleone believes, man cannot be man, and men who put their trust in the contrary type, represented by the American Gesellschaft, have ceased to be fully human and lack the virtu that Machiavelli commends. “You can act like a man,” the Don roars at Fontane when the singer weeps and whines in despair about his misfortunes. For all the contrast between legitimate and criminal society, at last, when the final mask is torn off, there is no difference at all; the Corleone family is based on fraud as well as force, and it does indeed melt into and become indistinguishable from America.

These are beliefs deeply shared by Michael Corleone himself, though not at the beginning of the novel, when, telling Kay about his family, he says, “That’s my family, Kay. It’s not me.” Michael enlisted in the Marines in World War II, despite his father’s arrangement of a draft deferment for him, to show his rejection of his family and his heritage, and his ambition to go to law school and marry Kay show his aspiration, the same as Bonasera’s, to melt into the American pot. Yet blood will tell. The attempted murder of his father and the attack on his family draw Michael naturally back to his roots, and his exile in Sicily completes his assimilation into the Gemeinschaft and the ethnic heritage he had rejected.

The polarity of Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft is clear in the novel and in Part I of the film series, but in Part II, something else develops, introducing yet another level of meaning. In the book and Part I, the Corleone family is radically distinct from the “normal” Gesellschaft society of America. In Part II, however, the family itself is changing, and the evolution is already well under way when the film opens. Divided into flashback scenes describing the youth of Vito Corleone in New York’s Little Italy in the 1920’s and the main story set in the late 1950’s in Nevada and Cuba, much of the film action in Part II plays off corresponding scenes from Part I, and the flashback sequences offer subtle commentaries on sequences from the main story line. The integration of film sequences and plot make brilliantly clear the evolution that is taking place inside the Corleone family itself and in the larger society for which the family remains a metaphor.

Thus, the opening scene in the main story line of Part II is the confirmation of Michael’s son, Anthony, in the Catholic Church, a sequence that corresponds to and plays off of the opening wedding sequence from Part I. But while the wedding sequence is an immersion into pure Gemeinschaft, the confirmation sequence by contrast reveals that Gesellschaft is rapidly catching up with the Corleones. At the wedding, the band is Italian, and the guests sing and dance with the band to traditional Sicilian wedding music. In the confirmation sequence, a professional orchestra and professional dancers perform, and none of the musicians is Italian or knows Italian music. At the wedding, the police are kept out of the reception, though they observe the whole celebration from their cars, and Don Corleone’s pet judges and politicians are invited but politely decline to attend. At the confirmation, the mafiosi take state troopers plates of food, and the guest of honor is Senator Geary, himself a crook and an almost comic hypocrite. If the family is being corrupted, it is because it is being assimilated into the existing corruption of American Gesellschaft.

The whole confirmation sequence, in contrast with that of the wedding sequence in Part I, shows a new twist of the dominant metaphor of the novel and films. The novel and Part I established the metaphor that criminal society is analogous to normal or legitimate society. The point of the metaphor was to offer a critique of normal society, not for its resemblance to criminal society but for its departures from the more natural norms that govern the Gemeinschaft of the criminal family. Now, in Part 11, the new development is that the family is itself becoming part of the normal society and thereby is being corrupted. A religious sub-metaphor is employed to show the corruption through the confirmation reception; just as the baptism ceremony of Part I made Michael a godfather in both the religious and criminal senses, so the confirmation sequence receives Michael’s son into the Church at the same time that the family is received as part of America, as part of the corruptive Gesellschaft.

A large part of the conflict in Part II revolves around the antagonism between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft within and without the family. There is a dual conflict, one between the Corleone family and the Gesellschaft syndicate led by the greedy and treacherous gangster Hyman Roth, and a second between the forces of corruption within the Corleone family itself. The logic of Michael’s power dictates that he do business with Roth and make tactical sacrifices of the interests of his subordinates, mainly his aging lieutenant Frankie Pentangeli, who is the voice of pure Gemeinschaft. Pentangeli’s complaint is that Michael is putting the interests of “that Jew in Miami” over those of “your own blood” and that Roth and his allies are avaricious and untrustworthy, recruiting “spies” and “niggers” instead of good Sicilian boys to run the rackets in New York. Moreover, the Roth gang is obsessed with drugpeddling and prostitution instead of the gambling that was the backbone of the Sicilian gangs before and after Prohibition. The picture Pentangeli paints of the Roth gang and its activities and procedures is one of Gesellschaft—an organization devoted purely to material acquisition and sensory gratification through rational, calculative enterprise, an organization contemptuous of the traditional bonds of Gemeinschaft in the forms of the deference, manners, and ethnic and kinship loyalties that characterized the Corleone family in the past. Roth’s gang is multiethnic, and his consigliore is a Sicilian, Johnny Ola.

But despite Pentangeli’s complaint, it is actually Michael himself who is desperately trying to preserve the Corleone family, and it is his tragedy that the process of modernization by which Gesellschaft invades and corrupts the Corleones is irresistible. His sister Connie has virtually deserted her own family and seeks only money from Michael. His brother Fredo is seduced by Roth and Johnny Ola into betraying Michael and jeopardizing his life. His wife Kay aborts their unborn child in what is an act of war against the family itself. Troubled by the crumbling of his family, Michael asks his mother, the widowed Mama Corleone, “by being strong for his family, could Pop lose it?” To the old woman, still immersed in Gemeinschaft, the question is not even meaningful. “But you can never lose your family,” she answers. “Times are changing,” Michael replies.

Michael’s tragedy is precisely that he is strong for his family and tries to arrest the rot, an effort that meets with only hatred and betrayal from family members who insist on putting their own gratification above that of the family. “He said there was something in it for me,” whines Fredo when Michael demands to know why he collaborated with Johnny Ola. The contrast with the Gesellschaft of Hyman Roth is powerfully clear when Roth angrily explains why Michael’s questions about Roth’s attempted killing of Frank Pentangeli are out of line. Roth reminds Michael of Moe Greene, a man whom, “as much as anyone,” Roth loved as a friend, and when “someone” (namely, Michael) ordered Greene killed, Roth says, “I never asked who gave the order—because this is the business we’ve chosen.” To Roth, crime is merely business, a purely acquisitive and calculative activity, that ought to be immune to the sentiment and bonds of honor imported by Michael. To Michael, however, attacks on him, his family, and his dependents must be avenged, as was the case also with his father, who returned to Sicily some forty years after the murder of his own family to take vengeance on the Mafia Don who killed them.

At the end of Part II, yet another bloodbath ensues that is reminiscent of the massacre at the end of Part I and parallels the flashback of Vito Corleone’s killing of Don Ciccio in Sicily. Michael insists on having Roth killed, along with Fredo and Pentangeli, who has fallen into the hands of the FBI as a witness. “Do you have to wipe out everybody?” Tom Hagen asks Michael. “No,” Michael replies, “Only my enemies.”

The bloodbath is perfectly logical, not only as a fulfillment of the vendetta that a Gemeinschaft recognizes and demands, but also as an act of power. Only Roth’s death will confirm Michael’s victory and remove a still dangerous enemy. Fredo is a living liability and is too stupid and weak to be trusted under any circumstances. Pentangeli knows too much and has been prevented from incriminating Michael only by pressure against his brother; he too is too dangerous to be allowed to live. In each case, Michael’s insistence on their executions is, from the point of view of the Corleone power interests and from that of the moral code of the Gemeinschaft, logically essential and morally unobjectionable. The bloodbath and Michael’s isolation at the end of Part II are confirmations not, of the corruption and arrogance of power but of the inexorable logic of power—only by being strong for his family could Michael hope to preserve his family, but by being strong for it, he destroyed it. That was his tragedy, as it is the tragedy of human society. Power is not only necessary to the functioning of society, as Machiavelli taught; it also possesses a relentless logic that eventually eats up itself as it irre

Leave a Reply