Detroiters have a deeply ironic way of looking at their beloved city. The irony is evident in a once-popular T-shirt that showed a muscular tough gripping a ferocious dog around the neck while holding a loaded gun to the animal’s head. “Say Nice Things About Detroit,” the T-shirt read. The T-shirt is a commentary on Detroit’s international reputation as a rough working-class industrial town where cars are built and more than one dispute has been settled with fisticuffs.

Detroit came of age in the 20th century as a city of struggle. Two in particular have withstood history’s test. The Battle of the Overpass took place in 1937 in nearby Dearborn, pitting Henry Ford’s security chief Harry Bennett and his goons against Walter P. Reuther, Richard Frankensteen, and organizers from the nascent United Automobile Workers (UAW). The battle ended in bloodshed and a social contract, largely forgotten by today’s yuppie journalists, that dramatically improved the economic lives of millions of working-class Americans for two generations. The UAW agreed to supply the automobile companies with labor; in exchange, the auto companies provided union members with salaries decent enough to afford a middleclass existence.

The Riot of 1967, an urban uprising of the poor, produced a sadder ending. Forty-three people were killed in five days of the most costly rioting, at the time, in U.S. history. As Paige St. John wrote in a recent piece for the Sunday Journal, a weekly produced by striking workers at Detroit’s two dailies, the Free Press (Knight-Ridder) and News (Gannett), Detroit’s white liberal mayor, Jerome P. Cavanagh, “had told America that he could weave a net of social programs that would not just catch but uplift the urban poor. The Kennedy administration financed it. America believed it. Cavanagh’s strong Irish face shone on the inside pages of Newsweek and on the cover of Look magazine.” As riots flared in other cities, Cavanagh thought Detroit would be spared. After all, Detroit was the town where Bobby Kennedy rode in an open-air convertible, shaking the hands of the urban poor, an image caught in a memorable photo that seemed to offer so much hope. Yet there it was, burning before the world for three days while crafty President Lyndon Baines Johnson delayed Michigan Governor George Romney’s request for federal troops. Cavanagh’s son Mark, today a judge, believes Johnson used the riots to puncture Romney’s hopes for the Republican presidential nomination. He is not alone.

But there is a deeper irony at work in “Say Nice Things About Detroit.” The slogan was coined by a local suburban shopkeeper and civic booster, Emily Gail, who later moved to Hawaii. News columnist Pete Waldmeir, the closest thing Detroit has to a Mike Royko-style journalist, had a different suggestion: “I’m talking about settling on a new slogan for Detroit—something catchy that folks from around the country and the world will immediately identify with my hometown.” Waldmeir writes:

New York is the Big Apple. Chicago is the Windy City. New Orleans is the Big Easy and Philadelphia’s the City of Brotherly Love. . . . Even European cities have identifying monikers. Paris, for instance, is the City of Lights; Rome is the Eternal City . . . Detroit, alas, has had many different tags hung on it over the years . . . Motor City . . . Arsenal of Democracy . . . Motown . . . Murder City . . . Too many of the bad ones have stuck.

“My personal candidate?” Waldmeir writes. “For years I’ve proudly worn a T-shirt that says all I have to say: ‘Detroit: No place for wimps.'”

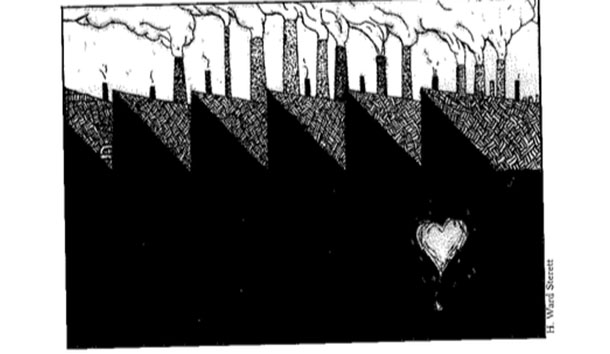

Detroit is no place for wimps. For most of the 20th century, its reputation has been as the tough, working-class town of Hard Times or Hoffa. Ford’s Rouge complex, where the Battle of the Overpass took place, is still one of the largest industrial facilities in the world. Suburban Downriver is one of the most heavily industrialized areas in the United States. From atop the Rouge River bridge, you can see the Rouge complex to the north; to the south are Downriver’s auto plants and steel mills, some now shut down as a result of the North American Free Trade Agreement. But the view cannot match the pungent odor that assaults one’s nostrils on hot summer days, a chemical melange that sometimes smells like rotten eggs.

The irony of Detroit is reflected in the way area residents identify with the city, whether they live in it or the suburbs. Some suburbanites answer “Detroit” when they are out of town and asked their place of origin. There is a pride associated with the Detroit of automobiles and Motown Records, whose performers gave the world so many chart-topping hits before moving to Los Angeles in the early 1970’s. But when they are back in Southeast Michigan, the answer of these suburbanites is more likely to be “Birmingham,” “Dearborn,” or “Livonia.” There is only shame for the Detroit of Murder City fame, of streetlights that do not work and snow-covered streets that went uncleaned during last year’s international auto show. And bitter memories of the Detroit of Israeli author Ze’ev Chafets’ book, Devil’s Night, which told the world about the tradition, since ended, of wholesale arson on the night before Halloween. Or the Detroit analyzed by New York’s leftist Village Voice under titles such as “Motor City Breakdown” or “New Jack City Fats Its Young.” Some of the most honest coverage of Detroit’s problems has been written not by native or transplanted liberals but by outsiders with a left-of-center perspective. The same holds true for the auto industry; it was ex-New York Times reporter David Halberstam who wrote The Reckoning, which documented how Ford responded to Japanese penetration of U.S. auto markets.

Suburbanites’ love-hate relationship with Detroit is not lost on the city’s black population, which exceeds 75 percent. To black Detroiters, it is rank hypocrisy for white suburbanites to identity with the city when outside of Michigan while disowning it locally. This is only one divide separating Detroit from the suburbs. Within Detroit, the late Coleman Young, elected in 1973 as the city’s first black mayor, is viewed reverently; in the suburbs, he remains anathema. And no wonder: Shortly after taking office, the former civil-rights activist told Detroit’s criminals to “hit Fight Mile Road,” the boundary between the city and its northern suburbs. Young served as mayor for 20 years; his tenure proved the old saw that “politics makes for strange bedfellows.” Supported by the Communist Party, he worked with Henry Ford II to build the Renaissance Center, a major commercial development downtown. A Democrat, Young nevertheless enjoyed a closer working relationship with two Republican governors (William Milliken and John Engler) than with his fellow Democrat, Governor James Blanchard. In 1991, Young’s tenure ended with the election of black Detroit attorney (and former chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court) Dennis Archer, attacked by opponents as the candidate of the white suburbs. Conventional wisdom is that Archer ushered in a new era. But the problems of Detroit, whether city or suburb, are more complicated and desperate than its three million metropolitan residents have been led to believe. They are rooted in international trade and the cold hard reality of the economic principle known as Factor Price Equalization (FPF).

“There prevails on the whole earth a tendency toward an X equalization of wage rates for the same kind of labor,” wrote Ludwig von Mises. The Austrian economist Mises escaped the Nazis but not the stigma of being a non-Keynesian in the groves of post-World War II academe in America. But the small group of students he influenced included Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who peppers his congressional testimony today with terms straight out of Mises’ magnum opus, Human Action.

What Mises described with FPF was the tendency of the prices of wages and other factors (such as land and capital) to equalize when government-imposed barriers to international free trade are ended. Investment from across the world will move to the nation offering the highest rate of return to investors. In the case of NAFTA, there are skilled and unskilled workers in both the United States and Mexico employed by the automobile industry and its suppliers. Capital will flow into the sectors offering the greatest return to investors (U.S. skilled and Mexican unskilled labor) and out of those sectors providing a lower rate (Mexican skilled and U.S. unskilled labor). Consumers ultimately benefit, but there are clear winners and losers under this process. If yon are a $50-per-hour American computer geek or a $5-per-day Mexican blue-collar worker, capital will flow your way because your work provides the greatest return to investors in the global economy. But investors in Mexican skilled and U.S. un.skilled labor also want a higher rate of return, and to achieve this, they must spur productivity increases, generally with technological advancements—or worse. Corporations must downsize, outsource, or send native jobs to a foreign land. Unskilled American blue-collar workers end up the biggest losers.

Manufacturing jobs, especially for unskilled workers, have been disappearing from Detroit’s auto industry because of the emerging global economy and FPF. General Motors, the largest automaker, has eliminated more than 250,000 jobs in two decades. Ford announced a major change of strategy in July (outsourcing to Brazil) and has also been trimming jobs. The process was already well under way at Chrysler before it was swallowed by foreign investors and became Daimler-Chrysler; now, only about 25 percent of its shareholders are American. The process is just beginning. As more international trade agreements are concluded, FPF will kick in with a vengeance, someday incorporating lower-wage nations such as India and China with their several billion inhabitants.

What is to become of the Motor City, the once-great Arsenal of Democracy, the industrial titan that defeated the Nazis in World War II?

What occurred in Detroit during World War II was remarkable, although it has been largely forgotten today by the younger generation. In December 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared in a fireside chat that America “must be the great Arsenal of Democracy.” At the time, FDR was talking about planes, boats, arms, and munitions. War. And it was war, not FDR’s New Deal or Keynesian economics, that brought an end to the Great Depression.

When the war began, Detroit’s auto companies, in alliance with the UAW, converted their peacetime plants into war-time factories that churned out tanks, aircraft engines, boats, cannons, even airplane tires. At its height. Ford’s Willow Run Plant near Ypsilanti produced one twin-tailed B-24 Liberator airplane every hour. Women played a key role in war-time production; Rosie the Riveter filled Detroit’s defense plants. Michigan had only two percent of the U.S. population but was producing more than ten percent of the nation’s war goods. If the Nazis could have bombed Detroit, they would have. “Detroit,” Joseph Stalin once quipped to FDR, was “winning the war.”

Those glory days are gone. A three-tier economic system is being created today in Detroit, although the process is slow and not easily discernible.

First, there is the white-collar suburban entrepreneurial and managerial class, including high-tech engineers, computer code writers, and those of us who live by words, symbols, and images in the Information Age. Second, there is the urban underclass, situated primarily in Detroit itself Then there is the third group: the invisible blue-collar workers whose families were the main beneficiaries of the social contract between the auto companies and the UAW. For most of the 20th century, their manufacturing jobs brought the promise of a modest house, a car or two, braces, and maybe college someday for the kids, along with a small cottage on a lake “up north.” Real per capita income has grown in recent years for the first group but fallen for the latter two. The underclass never had a middleclass lifestyle; the invisible third group is losing it. Increasingly it is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve middle-class status without significant personal debt. Many families in this group are not living beyond their means because they want to; they are assuming large debt burdens to survive.

Free-market conservatives and libertarians contend that international free trade leads to greater economic efficiencies and consumer choice. At their basest level, free traders resort to Social Darwinism. “If some autoworker in his 40’s with a wife and three kids is laid off,” a 20-something New York neoconservative told me recently, “that’s his problem, not the country’s. He should learn how to use the computer!” Savvier free traders acknowledge the social cost of middle-age families surviving on three or four service-sector jobs after downsizing. “It’s a very real problem,” a conservative ex-Federal Reserve economist confided. But they offer few answers other than job retraining and more education. Nor do they need to. The free traders are winning the public-policy debate; Bill Clinton, a Democrat, signed NAFTA, and more international free-trade agreements are likely to occur.

The U.S. economy is about to set a record for consecutive months of economic expansion. There is talk on Wall Street of a “New Economic Paradigm” that has repealed the business cycle. But surface appearances can be deceiving. The auto industry is cyclical by nature, as those of us who grew up with it know. (My father worked 43 years building engines at Chrysler.) Eventually a recession will occur, and Detroit will lose more manufacturing jobs. The dynamic of capitalism is more powerful than commonly understood. Joseph Schumpeter called it “creative destruction.” One could also describe it as the “downsized autoworker’s lament.”

Politics has its limits. In the 1995-96 session of the Michigan House of Representatives, I served as Republican chair of the Urban Policy Committee. “Don’t take it,” a senior colleague from a rural Republican district told me when I was offered the post. “They [the leadership] want you to fail.” This paranoia was matched by the cynicism of a Democratic colleague. “Republican urban policy,” he told me, “is a contradiction in terms.” Despite the challenges, we were able to forge a bipartisan coalition and approve an interesting piece of Republican legislation creating tax-free “Renaissance Zones” in depressed urban areas of Detroit.

Now Detroit provides two contrasting political urban policies: Governor Engler’s Renaissance Zones and federal Empowerment Zones, championed by President Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. “By creating . . . new zones in America’s urban and rural communities,” Gore declared in April, “we will bring the spark of private investment to the communities that need them the most—and we will spread the lessons of community empowerment across the country.” Empowerment Zones allow distressed communities like Detroit to use “targeted federal benefits as part of a strategic revitalization plan to encourage significant new private investment and job creating opportunities within these areas.” In Detroit, more than two billion dollars in private-sector financial and technical assistance commitments have been pledged. But serious problems have emerged. Last November, federal auditors found the agency in charge of Detroit’s Empowerment Zone had overstated its accomplishments and failed to notice when tax dollars were incorrectly spent outside the district. Anyone with the time to dig deeper will find that a majority of the top “economic development” projects in Detroit are not legitimate private sector investments but government action that tries to leverage taxpayer money, including $172 million for “demolition and renovation” work by the Detroit Housing Council at two government housing projects.

Detroit’s failing public schools, taken over by the state earlier this year, provide one more ironic twist. In recent decades, even militant free traders have been forced to acknowledge that the distribution of earnings reflects the distribution of formal education. The gap between the well-educated and the not-so-well educated is growing. Real median family income in the United States doubled from the end of World War II to the recession of the mid-1970’s. But the real standard of living for those without a college degree has steadily and sharply declined since that time. The picture is even bleaker for those without a highschool diploma. A lifetime of economic desperation is all but certain for those dropping out of Detroit’s public schools. It has not always been this way. For much of the post-World War II era, high-school graduates and even dropouts were able to find the unskilled auto and steel jobs that provided a middle-class lifestyle. The irony? Today, their unskilled counterparts in Mexico, Brazil, and Asia still can.

Leave a Reply