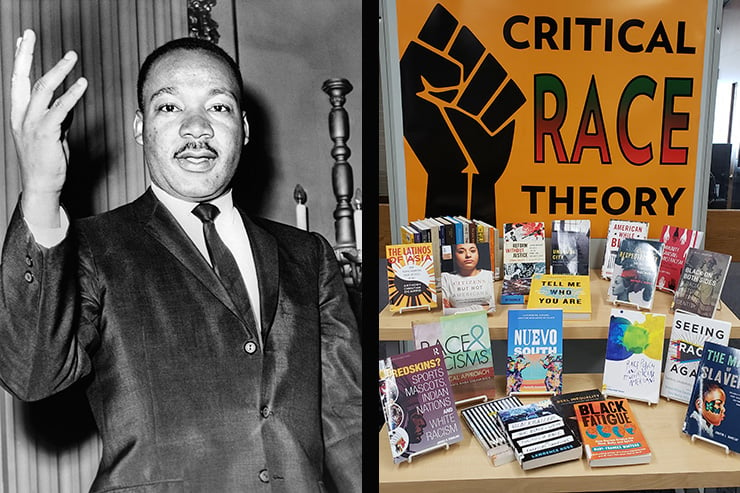

Nearly a decade into what has been called “The Great Awokening,” fanatical racial wokeness shows little signs of abating. The pieties of critical race theory (CRT), which we are told is not being taught anywhere, are now authoritative. Everything is racist. It’s never the fault of black people. And America can never sufficiently abase itself for the “original sin” of slavery.

To counter the madness, many invoke the moral authority of Martin Luther King, Jr., arguably the most admired person in recent American history. As House Majority leader Kevin McCarthy once explained in an interview: “Critical race theory goes against everything Martin Luther King has ever told us—don’t judge us by the color of our skin—and now they’re embracing it.”

McCarthy obviously had in mind the most famous line from King’s most famous speech. King, as we all know, expressed the hope that America would one day judge people not by “the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Fewer, however, know that his road to colorblindness was paved with racial preferences and reparations.

Like the critical race theorists of today, King demanded equal outcomes between blacks and whites in all realms. He wrote in his last book, Where Do We Go from Here?,

… if a city has a 30 percent Negro population, then it is logical to assume that Negroes should have at least 30 percent of the jobs in any particular company, and jobs in all categories rather than only in menial areas, as the case almost always happens to be.

This wholly unwarranted expectation is the cornerstone of both the modern civil rights regime and critical race theory. It has, of course, since been expanded to cover all other purportedly victimized identity groups. It provides the justification for the totalitarian doctrine of disparate impact, now enshrined in our laws, which “makes almost everything presumptively illegal,” in the words of Gail Heriot, a member of the United States Commission on Civil Rights. What standard, law, or norm, after all, produces no disparate outcomes across all parts of the population?

If it is “logical” to expect proportional representation, then any disparity that cuts against blacks is inherently suspect, and it soon becomes just as “logical” to blame racism for all such disparities, as CRT does today. In the words of America’s leading charlatan on racial questions, Ibram X. Kendi: “when I see disparities, I see racism.” The words are not King’s, but the underlying sentiment is.

It is particularly revealing that King expected blacks, in his hypothetical example, to have “at least 30 percent of the jobs in any particular company.” They could always have more. As we see today, disparities that cut against white people are not evidence of racism. Major League Baseball is deemed racist because it’s not black enough, but Harvard is deemed equitable, even though blacks are overrepresented in its incoming freshman class. Only prisons can be “too black.”

In order to produce the right outcomes, King supported what we today euphemistically call “affirmative action,” but which he more honestly called “special treatment.” As he explained in Where Do We Go from Here?,

It is, however, important to understand that giving a man his due may often mean giving him special treatment. I am aware of the fact that this has been a troublesome concept for many liberals, since it conflicts with their traditional ideal of equal opportunity and equal treatment of people according to their individual merits. But this is a day which demands new thinking and the reevaluation of old concepts. A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years must now do something special for him, in order to equip him to compete on a just and equal basis.

America has spent the ensuing five decades doing “something special” for black people, primarily by lowering or abolishing standards in almost every institution, from higher education to classical music, to boost representation. Regardless of what the Supreme Court rules in the affirmative action cases before it, racial preferences to benefit blacks (at the expense of Asians and whites primarily) will remain the norm in America. By King’s reasoning, centuries of affirmative action may be warranted to compensate blacks for the “hundreds of years” of discrimination.

King did believe that these programs would one day no longer be necessary, that eventually, blacks would be able to “compete on a just and equal basis” with whites: i.e., to be proportionally represented in all realms, without any special help to compensate for their past mistreatment. Colorblindness, for King, meant equal outcomes. Until the “right” racial outcomes were achieved, racial preferences—judging people by the color of their skin—would be the norm.

King also supported reparations. As he explained in Why We Can’t Wait, a title that very much captures the spirit of today’s woke fanatics,

No amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America down through the centuries. Not all the wealth of this affluent society could meet the bill. Yet a price can be placed on unpaid wages. The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of the labor of one human being by another. This law should be made to apply for American Negroes. The payment should be in the form of a massive program by the government of special, compensatory measures which could be regarded as a settlement in accordance with the accepted practice of common law.

At the policy level, MLK thus converges with the “crits,” as the CRT ideologues calls themselves. Both demand equal outcomes between blacks and whites. Both support racial preferences that benefit blacks. And both support reparations.

Where the crits break with King is at the rhetorical and aspirational level. CRT is a bleak worldview. It posits that the racial problem is insoluble and that blacks must abandon all hope of ever being treated fairly in America. “You have been cast into a race in which the wind is always at your face and the hounds are always at your heels,” Ta-Nehisi Coates tells his son in Between the World and Me.

The crits end up teaching blacks to hate America and white people. Hatred of whites, it is true, is rarely openly preached (though the mask does occasionally slip), but it underlies the whole ideology. As Stokely Carmichael exhorted the followers of his Black Power movement (which essentially became CRT once it entered the academy), “We must fill ourselves with hate for all things white.”

King admited that, as a young boy, he too “had determined to hate every white person.” But he eventually “conquered” this “anti-white feeling” in college after meeting white students who were well-disposed toward blacks. In his public rhetoric, he generally preached brotherhood, love, and forgiveness. King, after all, was a Christian (however unorthodox elements of his theology may have been). “The Negro must show that the white man has nothing to fear, for the Negro is willing to forgive,” he wrote in Where Do We Go from Here? Forgiveness is, of course, anathema to CRT, which aims to foster grievances in perpetuity so as to leverage them for benefits.

King also never lost hope in America. “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair,” he intoned in his speech before the Lincoln Memorial. “And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.” To that end, King was particularly critical of the dispiriting teaching of Black Power. Again, from Where Do We Go:

Black Power is a nihilistic philosophy born out of the conviction that the Negro can’t win. It is, at bottom, the view that American society is so hopelessly corrupt and enmeshed in evil that there is no possibility of salvation from within.

Given King’s moral stature in contemporary America, conservative critics of CRT may be tempted to cobble together a “conservative King” from these and other passages in his writings. Start with the quotation from the “I have a Dream” speech; add in the invocations of the Founding, and top it off with some vague appeals to love.

This, however, is a losing strategy.

The seemingly conservative elements of King’s thought are ultimately dwarfed by the radical ones. Setting aside his own moral turpitude, King had Marxist sympathies, fiercely denounced capitalism, called for massive welfare programs (beyond anything that FDR, LBJ, or Obama would even imagine), and did not hesitate to broadly condemn whites—“I am sorry to have to say that the vast majority of white Americans are racists, either consciously or unconsciously,” he told a black audience in 1968.

MLK also made excuses for violent rioting. It “cannot be taken for granted that Negroes will adhere to nonviolence under any and all conditions,” he warned. “A riot is at bottom the language of the unheard.” This line became a slogan for the left during the Black Lives Matter and Antifa riots in the summer of 2020.

Even if it were possible to somehow retrofit MLK into some sort of a conservative by very selectively citing him, such a sanitized King would not actually be helpful in the fight against wokeness. To recognize King’s moral authority is to accept that the fight against white racism remains the most pressing issue of our time. It is to accept the transvaluation of values, effected by the Civil Rights Movement, which has made racism the one unforgivable sin and its eradication the new categorical imperative. It is to strengthen the reigning understanding of politics as a process by which (purportedly) oppressed groups protest to get their (special) rights. Lastly, it is to allow the past injustices committed against blacks to loom larger in the collective historical imagination than any of the country’s glorious accomplishments. All this plays into the hands of the crits, and the woke left more generally, by confirming the essentials of their worldview.

In the fight against wokeness, the right really has no choice but to decanonize King. He does not belong in the pantheon of great American statesmen and should only be cited with reserve and strategically. Where he does belong is in the pantheon of leftist activists. MLK’s eldest son, Martin Luther King, III, ultimately got it right when he said that conservatives “choose little tidbits of what he said and not the full message in its totality.”

Leave a Reply