The decline of the Midwest as a cultural force was well under way by the time Russell Kirk was born in Plymouth, Michigan, in 1918. Yankee influence in the region had largely been replaced by a more vibrant German-American culture, and now the United States, in the midst of the War to End All Wars, was engaged in a war against that culture on the homefront. The period between 1914 and 1933 would prove crucial. By the time Kirk entered junior high, he was forced to take a course in civics—“a Deweyite innovation,” as he described it. Today, of course, conservatives rise up in arms at any attempt to remove civics courses from the public-school curriculum. But circa 1930, those courses were an important part of the attempts—directed from Washington, D.C., and East Coast academia—to wipe out regional and ethnic differences and to make all citizens generically American. In the Midwest, those assaults were all too successful.

Kirk continued his education at Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, known today simply as Michigan State University. After he received his M.A. in history from Duke University in 1941, he entered the U.S. Army and spent the entire war at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, rising to the rank of staff sergeant in the Chemical Warfare Service.

Between 1946 and 1952, Kirk spent one semester a year teaching history at Michigan State and the rest of his time in doctoral studies at St. Andrews, the senior Scottish university. Upon graduation, the first American to receive the Doctor of Letters degree from St. Andrews, Kirk briefly taught full-time at Michigan State before resigning in disgust over the college’s poor academic standards. (When, as a junior at Michigan State 36 years later, I first met Dr. Kirk, I asked him what he thought of MSU’s current academic standards. “Uhhmm. Much worse,” he replied. A prolific writer, he could also be a man of frighteningly few words.)

The same year that Dr. Kirk left Michigan State, he published his most famous book, The Conservative Mind, and made a surprising decision that would shape the rest of his life. Despite the almost complete intellectual marginalization of the Midwest, Dr. Kirk did not accept offers to teach at Yale or the University of California at Riverside, universities that would have provided him a certain standing in American intellectual life; instead, he took possession of Piety Hill, his mother’s ancestral home in Mecosta, Michigan. Both the home and the town had been built by Amos Johnson, Dr. Kirk’s great-grandfather. Johnson’s uncle, Giles Gilbert, had been the lumber baron of Central Michigan, one of the men responsible for the almost complete destruction of the vast pine and hardwood forests that once completely blanketed the glacial soils of Michigan. During the lumber boom of the 1880’s, Mecosta’s population reached its high point of 2,000. By the time Gilbert departed for Oregon in the late 1800’s (pursuing “the retreating trees,” as Dr. Kirk would write), few trees remained in Central Michigan—or, indeed, across the state. Because the soil in Mecosta County was so poor, the land was still largely barren when Kirk arrived in 1953, its flatness broken only by the remains of the massive stumps that the loggers had left behind.

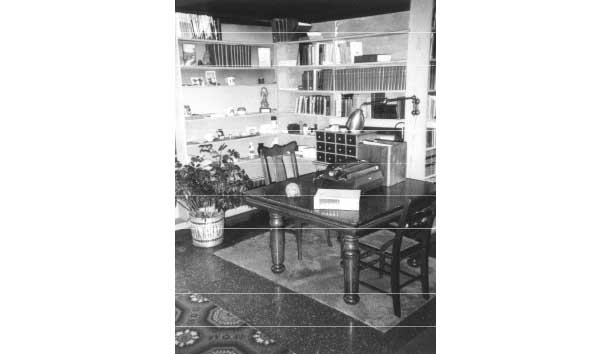

It was at Piety Hill that Dr. Kirk wrote almost all of his 30 books and hundreds of articles and reviews, and it was there that he tried to live what he called “a life of decent independence, living much as his ancestors had lived, on their land, in circumstances that would enable him to utter the truth and make his voice heard: a life uncluttered and unpolluted, not devoted to getting and spending.” It was there that he brought his wife Annette, a Long Island native, in 1964; and there that they reared their four daughters, Monica, Cecilia, Felicia, and Andrea. And it was there, in the midst of a village now reduced to fewer than 200 people, that Dr. Kirk came to view himself as a Northern Agrarian.

The Jeffersonian vision of decentralized power, small-scale living, and the yeoman farmer captured Dr. Kirk’s imagination. Like the Southern Agrarians, he saw that vision increasingly threatened by industrialization and the heightened pace of technological change, and he knew intimately what his own ancestors’ shortsighted obsession with progress and profit had wrought in the landscape around Piety Hill.

During his college years, Kirk spent his summers as a guide at Greenfield Village, where he met Henry Ford. Later in life, Dr. Kirk would come to believe that Ford incarnated both the best aspects of America in the 19th century and the worst of America in the 20th. “Henry Ford,” he wrote,

had the instincts of an antiquary, but also the practical talents that had effaced the rural life and the farmlands where he had been born and reared. Behind the serpentine brick walls of [Greenfield] Village, he had preserved the simple house of his birth, the rural school he had attended, and other buildings of his boyhood. . . . So far as it lay in his power, Henry Ford endeavored to save from extinction the rural society of his boyhood; but multimillionaire though he was, all his capital seemed trifling beside the forces of indiscriminate growth that he . . . had set into operation . . . He had made it possible for almost anybody to whiz about in a motorcar, escaping for a time from private tribulations; possible also to dwell many miles distant from one’s place of employment; possible as well for couples to court in a mobile privacy, for malefactors to prowl and escape with ease, for tipsy youths to blot out others’ lives and their own on icy roads, for entrepreneurs to pull down every handsome old house that stood on a corner lot so that gasoline stations might rise there.

Ultimately, the two centuries could not coexist, not in Ford, and not in time. Dr. Kirk, seeing that the 20th century was draining the life out of his beloved Mecosta, threw his lot in with the older America. The automobile, he would later write, is “a mechanical Jacobin, overthrowing dominations and powers, breaking the cake of custom, running over oldfangled manners and morals, making the very air difficult to breathe.” “Although no social philosopher,” Dr. Kirk wrote in his memoirs, “Henry Ford surely must have perceived before he died (alone with his wife, in an unlit house, in 1947 . . . ) some of the consequences of the changes worked by himself and other great industrialists of the time.”

Dr. Kirk’s vision was not only Jeffersonian and agrarian but Romantic, and in his fiction, he was influenced more, perhaps, by Sir Walter Scott than by any other writer. Against both the excesses and the limitations of reason, he stressed the centrality of imagination, which he, like Irving Babbitt, believed played the primary role in forming man’s moral sense. Discussing the genesis of his own novels and short stories in Decadence and Renewal in the Higher Learning, Kirk writes that

The image . . . can raise us on high, as did Dante’s high dream; also it can draw us down the abyss. It is a matter of the truth or the falsity of images. If we study good images in religion, in literature, in music, in the visual arts—why, the spirit is uplifted, and in some sense liberated from the trammels of the flesh. But if we submit ourselves (which is easy to do nowadays) to evil images—why, we become what we admire. Within limits, the will is free.

“When I write fiction,” Dr. Kirk continues,

I do not commence with a well-concerted formal plot. Rather, there occur to my imagination certain images, little scenes, snatches of conversation, strong lines of prose. I patch together these fragments, retaining and embellishing the sound images, discarding the unsound, finding a continuity to join them. Presently I have a coherent narration, with some point to it.

Conservatives today, when they bother with Dr. Kirk at all, approach him as a moral and political thinker: They are often disturbed by his fiction. They examine Dr. Kirk’s ghost stories and fantasy tales (which will be rereleased by?Eerdmans in the fall of 2002) the way a deconstructionist approaches Shakespeare. What message is he privileging? How can these fantastic and spectral tales make us more moral? How can scenes of kidnapping, and haunting, and murder advance the conservative agenda in Washington, D.C.? In discussing Dr. Kirk’s fiction that way, they miss the very point. His tales are not meant to be didactic—though they are, Dr. Kirk would insist, products of the moral imagination, and, thus, the reader should be better off for having read them. Their purpose, however, is simply to tell a story—to reflect, and perhaps magnify, and certainly embellish, a portion of reality.

Why, though, did Dr. Kirk choose to write ghost stories and fantasy tales? Partly, of course, because he had always enjoyed such tales himself. More importantly, however, in the postwar, post-Henry Ford, industrialized, mechanized, materialistic world, what portion of reality needed more magnification and embellishment than the ghostly realm? How better than through ghost stories to awaken the human “products” of American consumer culture to the fullness of the world around them?

Surely Dr. Kirk did not really believe in ghosts? the modern conservative asks, proving that he has missed the point once again. Of course he believed in ghosts, and not simply because he was certain that he had seen them. As he wrote in his memoirs, “Both on authority and through his own insights and experiences, Kirk had come to understand that there exists a realm of being beyond this temporal world and that a mysterious providence works in human affairs—that man is made for eternity. Such knowledge,” he concluded, “had been consolation and compensation for sorrow.” “No doctrine,” he argued, “is more comforting than the teaching of Purgatory . . . For purgatorily, one may be granted opportunity to atone for having let some precious life run out like water from a neglected tap into sterile sands.”

Throughout the 20th century, horror stories and ghost stories converged, a disturbing development that inevitably involved the mixing of forms, the loss of distinctions—the turning of ghosts into demons, and demons into ghosts. This convergence is as destructive of a proper understanding of humanity as is the concurrent blurring of the lines between men and angels. Angels and demons share a nature, though the former is beatific, the latter fallen; but man (and his ghost) is a creature all his own. He is bound by space and by time. That is why, in a true ghost story, the ghost is always tied to a particular place, and why, when he appears, his manifestation reflects a particular point in time, in the clothes he wears or in other aspects of his appearance. While men can attempt to ignore their own nature and refuse to put down roots, their spirits—which, after death, now know the truth—cannot be anything other than rooted. Unlike the demon, the ghost does not, in the words of the ancient prayer to the Archangel Michael, “prowl about the world, seeking the ruin of souls.” Instead, the ghost seeks the expiation of his sins, which occurred in (or at least are tied to) the place in which he appears. As Dr. Kirk explained: “The resurrection of the flesh and the life everlasting are sought not so much that one should prolong his own existence but rather that beyond time one might explain and atone.” When his sins are expiated, the ghost goes on to his final destination.

Dr. Kirk’s agrarian vision and his relationship to the countryside around Piety Hill was shaped in large part by his own understanding of the need for atonement and expiation. Virtually from the first day that he became master of Piety Hill, he set about undoing his ancestors’ destruction of the countryside; he regarded his efforts at reforestation as his moral duty. He planted his first trees just to the west of Piety Hill, in Civilian Conservation Corps style—straight rows, front to back and side to side. Several years later, Dr. Kirk realized that, like the CCC, he had planted the rows too close together, and so, like his ancestors, he became (briefly) a woodsman. As time went on, he came to understand that the problem was not simply that his ancestors had removed all of the trees in Mecosta County but that they had destroyed the landscape. He soon abandoned the geometric, CCC-style plantings and tried to conform his efforts to the features of the land. Over his 40 years at Piety Hill, Dr. Kirk—aided by his family and numerous assistants and houseguests—remade the landscape of Mecosta County, replanting thousands of trees.

That landscape figured prominently in Dr. Kirk’s fiction, and not simply as a setting for his stories. I first met Dr. Kirk at a seminar at Piety Hill, organized by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. After lunch on the second day, he offered to take those of us who were interested on a walkabout through the countryside. By the time he had covered a quarter-mile, Dr. Kirk—who was 71 at the time—had left all but two of us well behind, and we two were wearing ourselves out just trying to keep up. The effort, however, was well worth it, because, as we walked along, Dr. Kirk would lift his walking stick every few minutes and say, for instance, “Uhhm. This is the house where I set my story, ‘Off the Sand Road.’ And that—that is the Sand Road.” Over the course of close to an hour and a half, we discovered that he not only knew every path, every field, every house, every tree within a few miles around Piety Hill; he had written about many of them as well, and not just in the stories that were explicitly set in Mecosta County.

At the time, I did not really comprehend what Dr. Kirk was doing in showing us those sights. Even five years later, when I reviewed his memoirs for Chronicles, I wrote that,

To his eyes, Mecosta, shunned and despised by the commissars of big government, big business, and big culture, was a Brigadoon. As a business partner of Kirk’s once remarked, “Russell, you are the last of the Romantics, and probably the greatest: for nobody else could make tales out of that God-forsaken Mecosta County.”

But, reading more of Dr. Kirk’s fiction over the last few years, I have come to realize that he was doing more than making tales out of Mecosta County; he was making Mecosta County, fleshing it out, giving it an imaginative depth and richness that it lacked—or that, at least, had disappeared by the time he took possession of Piety Hill. His fiction changed the face of Mecosta County as surely as did his incessant planting. When his children or his numerous assistants or his distinguished visitors at Piety Hill read those stories, they began to see the forest, not just the trees; they came to see that Mecosta was not just a crossroads on a map. It was—it is—the center of the universe for thousands of people, some of whom are now alive, most of whom are now dead.

In his fiction, Dr. Kirk remade not only the landscape of Mecosta County; he remade the landscape of his own life. He drew the central action and much of the dialogue of “The Princess of All Lands” (perhaps his best short story; certainly, one of the best loved) from an actual incident involving his wife. Mrs. Kirk had picked up a hitchhiker one cold October day, and the girl, who eventually revealed that she had a gun, ordered Mrs. Kirk to take her home to her father, where she intended to present her as a birthday gift to him. When they arrived at the house, in a remote section of Central Michigan, the girl got out of the car first, and Mrs. Kirk managed to slam the door and speed away. Up until this point, “The Princess of All Lands” very closely resembles Dr. Kirk’s account, in his memoirs, of the actual incident. But in “The Princess,” Mrs. Kirk’s character, Yolande, is forced out of the car and presented to the girl’s father and brother, who turn out to be ghosts who, when alive, had tormented her every seven years. The previous year, they had died in a shootout after kidnapping another woman. Yolande, recognizing them, tells them that they are dead, and then, Dr. Kirk writes,

In those three faces Yolande saw a fury and a ravaging doubt such as she never had glimpsed before. Risen from the bench, the three lost ones wavered before her, hands clutching at nothingness. . . .

Then the Princess of All Lands uttered the ancient formula, shouting it into the abyss: “Go ye cursed into the fire everlasting, which is prepared for the devil and his angels!”

Before her the three of them writhed, speechless in agony, seared, incandescent, disintegrating. Then, the virtue ebbing out of her, Yolande fainted in her chair.

While these ghosts were destined for everlasting damnation, they still had temporal sins that required temporal punishment, and Yolande, because of her relationship to them, becomes the instrument of that punishment.

Why did Dr. Kirk turn his wife’s terrifying experience into an even more terrifying story? Why not simply let the waters of time wash the memory away? His understanding of the nature of fiction makes the answer clear: Here was an opportunity to coax meaning out of an event that might otherwise serve to convince some people of the randomness and meaninglessness of life.

What a contrast with the common attitude—even among conservatives—toward fiction. Instead of regarding it as “silly” or “trivial” compared to the struggles of life, Dr. Kirk came to regard the imagination as our primary weapon in those struggles. That is why he gave the title The Sword of Imagination to his memoirs, which he composed in the third person, more in the style of fiction than of autobiography. One of the final paragraphs of that book, written shortly before his death, provides perhaps the best insight into Dr. Kirk’s approach to the world:

This present life here below, Kirk had perceived often in his mind’s eye, is an ephemeral existence, precarious, as in an arena rather than upon a stage: some men are meant to be gladiators or knights-errant, not mere strolling players. Swords drawn, they stand on a darkling plain against all comers and all odds; how well they bear themselves in the mortal struggle will determine in what condition they shall put on incorruption. His sins of omission and commission notwithstanding, Kirk had blown his horn and drawn his sword of imagination, in the arena of the blighted twentieth century, that he might assail the follies of the time.

With Dr. Kirk’s death on April 29, 1994, that blade may have lost its latest master, but its edge has not been blunted. If there is any hope for a revival of Russell Kirk’s Midwestern agrarian vision, it is largely because those who have read his works have had their imaginations awakened by the sunlight glinting off of his sword.

Leave a Reply