As 1969 rolled around and the decade was ending, I was six years old and living in a temperate Southern city a thousand miles from New York. Conflict came from wanting to stretch my feet into my brother’s half of the backest-back of our fake wood-sided turquoise station wagon; Vietnam had no meaning for me. I must have sat on my Dad’s lap as he watched the news, but I don’t remember the “living room war.” All I have are blurry memories of first grade. My idea of pill-popping was half an orange-flavored child’s aspirin. I was a 36-inch-high square; I was out of it.

Somewhere out there were the Columbia student strike, the Harlem protests, the antiwar flag burnings, women’s lib, problems in the schools, the riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, the King memorials; but not at my house. Remember that Richard Nixon was elected President in 1968, and even though he just squeezed through on the popular vote, and even though, yes, it probably would have been Bobby Kennedy if he hadn’t been assassinated, still, a year that elected Dick Nixon was not a year of real political revolution. The middle class was unmobilized. (A letter from a Mrs. Mildred Dodge of Sylvania, Ohio, that ran in Life in ’68 read: “Thank you for bringing us the wholesome, encouraging and beautiful picture of youth embodied in the Nixon-Eisenhower engagement.” Richard Nixon’s daughter Julie was to get married to David Eisenhower in December. “Such a sad contrast to the poor, lost children living in caves!”)

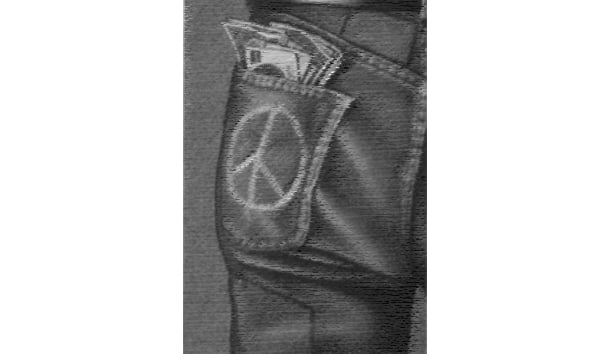

But in certain pockets out there in the wider world beyond my backyard, in the universities and bigger cities, it was a revolution, all right—a cultural and sexual revolution in this decade when lowbrow became highbrow and highbrows like Susan Sontag defended the switch, when the subculture became the culture, and the culture purposely ran amok.

Tom Wolfe, referring to his 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, told an interviewer:

“Everything I learned about what [Ken] Kesey and his group had been doing kept leading to something else, into more involved things. At one point I thought I’d never finish—I was reading books on brain psychology, on religion, on sociology, books on psychology, cognitive psychology, all sorts of things.

“I was gradually coming to the realization that this was in a way a curious, very bizarre, advance guard of this whole. push towards self-realization, and all these things that people are trying to avoid facing up to as the main concern. I think it’s very comforting to be able to say that we’ve got the same old problems: we’ve got war, we’ve got poverty.

“That way we don’t have to see that the main problem—if you want to call it that—is that people are free all of a sudden; they’re rich and they’re fat and they’re free.”

In 1968 Wolfe was already sporting those white suits. New York had two favorite sons running for President: Bobby Kennedy and Nelson Rockefeller. Joe Namath and the Jets won the AFL tide in December. Poet Marianne Moore was alive and well and living in Ft. Green, Brooklyn, where she would answer the door with pepper in her hand, ready to blind a possible attacker. Stephen Sondheim was doing word puzzles for the fledgling magazine New York. The newspapers were 10 cents. You could get a studio apartment in Manhattan for somewhere between $100-$250. You could get a bag of heroin uptown for around $3 to $5, which is also what it would cost you to see Joan Baez at the Fillmore East.

It’s funny to look back and see how old some of the heroes of that youth culture were. Ken Kesey, with his One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and acid tests and American flag tooth, was 33. Abbie Hoffman, who’d said “never trust anyone over 30,” was himself 34. Warhol was 40-something, Allen Ginsberg was 42, Norman Mailer was 45. (He published Armies of the Night in ’68, but he’d had his first big success with The Naked and the Dead 20 years before.) Timothy Leary was 48. Leonard Bernstein, with his benefit for the Black Panthers ahead of him, was turning 50.

These were the days when the black flag of anarchy was flying over the Brooklyn Academy of Music as the Living Theater performed there (in the nude, and encouraging their audience to fly); when New York was “a small town” and in most neighborhoods you could walk around at 3 A.M. and be perfectly safe; when during one winter, at least, if you wanted to you could really live in Central Park. America was going to start from ground zero and build a New Society; from that Utopia we somehow ended up with Watergate, the oil crisis, the BeeGees, and Mr. Goodbar.

More than one person has observed that what politicized young people in the 60’s was the single burning issue of the draft. No war, no 60’s. But we forget that for some people—and not just six-year-olds—their oblivion extended even to Vietnam. For her and her circle, says Cheryl Terry, then a model for Wagner and Ford, “Somewhere in the background we knew that there was a war, but it was almost as though we were living in a time capsule; we were so untouched by it. I never once remember anybody having a serious discussion about the war except to say we should get out or we should stay in. We didn’t have a political conscience. We were totally unaware of it. It was all across The New York Times every day, but our big thing was to laugh at the world and not to trust anyone over 30.”

As for “anarchists” like the late Abbie Hoffman, to be taken seriously was the last thing any of them wanted. Their lack of seriousness, or coherency, was in fact the point. “It is impossible for me to describe our ‘ideology,’ for we simply didn’t have one,” wrote Raymond Mungo, who helped run the Liberation News Service, a clearinghouse for the underground press. “We never subscribed to a code of conduct or a clearly conceptualized Idea Society, and the people we chose to live with were not gathered together on the basis of any intellectual commitment to socialism, pacifism, anarchism, or the like. They were people who were homeless, could survive on perhaps five dollars a week in spending money, and could tolerate the others in the house.”

Abbie Hoffman told an interviewer that, being miffed one night that a police inspector wouldn’t arrest him (“I kept telling him to bust me, and he kept saying I hadn’t done anything”), he looked around “and saw this display case, full of, like, Little League trophies,” the inspector’s favorite thing there in the station house. “And I just slammed into it.

“It was my favorite bust,” Hoffman said, “because it was so existential.”

Fred Eberstadt, a photographer then working for Life and Vogue, says, “In the early days at least there were few things more fun than marches. I went to a number of peace marches and black solidarity marches. I don’t mean to say they weren’t worthwhile, they probably were, but . . . it’s also true they were fun. It was kind of collegiate.”

He and his friends also used to go bail people out of jail all the time. One night when he went to bail out a friend who’d gotten busted at a protest at the Women’s House of Detention (then in Greenwich Village), he was surprised to find out the sit-in had been to legalize prostitution. “This girl was really quite a feminist, and I said, ‘How do you square legal prostitution with your point of view about feminism and antipornography?’ She said, ‘Well, I didn’t really know what it was all about. I’m so used to joining any demonstration I see that I just sat down where everybody else did.’ That was what it was for a lot of us,” Eberstadt continues. “Whatever the demonstration was, we’d join.”

The strike at Columbia was also typical. It was sort of about Columbia’s continued support of the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), which was doing research for the war; sort of about Columbia’s building of its new gym in Morningside Park in Harlem, which would have separate and unequal facilities for the community’s use; sort of about university president Grayson Kirk’s edict forbidding any protests inside university buildings. But IDA and the gym were more important as symbols of everything the students felt was wrong, than as issues in their own right.

Like many things, the Columbia strike was both so silly and so serious at the same time. While on the one hand there was the radical students’ admitted lack of a real agenda, still, the blacks in Hamilton Hall had weapons. During the strike one couple got married amid their fellow strikers at Fayerweather Hall. “Do you, Andrea, take Richard for your man?” the minister asked the bride. “Do you, Richard, take Andrea for your girl? I now pronounce you children of the new age.” One evening music professor Otto Luening, 87 years old and bridging a gap of several generations, showed his support by playing piano for the students in Low’s Rotunda. In a slower moment, James Kunen (author of the famous account of the strike, The Strawberry Statement) asked, “Was the Paris Commune this boring?” Then, on April 30, the police violently broke it up. Of the 712 arrested, 132 were injured. Some were beaten about the head and one girl was pushed by the cops (says Kunen) through a glass door. And yet in his book his somewhat dippy tone doesn’t change even after the violence. This quote is typical:

“Wed. July 19: I went to Washington, DC, for the rich people’s march in support of the Poor People’s Campaign. You are supposed to come away from these affairs with a renewed commitment and sense of purpose. I came away with two girls’ addresses and a slight tan.”

Andy the Icon

He is the great 60’s symbol, epitomizing all its releases, all its ironies, and all its sickness: if he didn’t sleep around and take drugs, he watched his friends do so, and in the era of flower children and communes he was unstintingly commercial. It was always l’art pour l’argent. He was the artist as art, the silent satirist, and when his irony encompassed his paintings, then that was just the biggest joke of all. “That Pop Art—I thought that was just s ” laughs Warhol “superstar” Viva, who did not hesitate to say as much. “Oh, I told him it was and he’d say ‘Well, gee, I can’t help it.’ We spent a lot of time deciding which paintings were lousy enough to throw out.”

People forget that the 60’s were also about money and commercialism; that this was the golden age of advertising; that men would give their dates $200 for a cab home—not in return for services, but just as pin money; that Huntington Hartford would walk into the bar Peartrees uptown and invite the crowd to come with him to the Bahamas: his plane was leaving at 10 o’clock. In New York there was even an element of commercialism applied to the hippies themselves. You could rent hippies for, say, your garden party, and you’d get real hippies, too, recruited off the streets downtown. Generally speaking, the worse they acted, the happier their renters were.

But Andy Warhol did not forget: all that free love and drugs was just hype, after all, and hype exists only to promote business. “Being good in business,” he said somewhere, “is the most fascinating kind of art.” He died with an estate worth several millions.

Emile de Antonio, a Marxist and documentary filmmaker whose Year of the Pig (on the Vietnam War) came out in ’68, says that “Andy was the ultimate voyeur, in that he never peeked. His presence was enough so that you did what the voyeur wanted.” In other words, he was the grand manipulator. “He had too much control over my life,” was Valeria Solanis’ excuse when she shot him nearly to death in June 1968. In a way, it seems almost inevitable that something like that should happen to him; he was always courting death, or at least filming it. And in a way he is even in being shot a symbol for that era: he went all the way out on some kind of moral limb, sawed it off, and lived to tell about it.

“He was not cut out to be his brother’s keeper,” art critic John Richardson said at his funeral, quoting with equanimity this famous retort of Cain’s. “The distance he established between the world and himself was above all a matter of innocence and of art.”

But if Warhol was the ultimate cynic, others are not. Cheryl Terry has mostly good memories. The word she keeps using is “fun”: “it was unbelievably fun.” The others I spoke to agree. Only looking back now from their 40’s and 50’s and 60’s, they remember the downside as well. Artist Charles Finch, who was a teenager at the time, came back from a concert in the late 60’s to find a friend of his who’d been tripping had jumped out a window and killed himself.

Eberstadt ran into a friend of his en route to a birthday party who was carrying along a paper bag lunch she’d bought at Bloomingdale’s. When Eberstadt pointed out that the hosts would probably be happy to feed her, she declared that she wouldn’t eat one single thing they were serving, “least of all cake.” He continues: “There was one party I heard of where somebody put acid in some kind of a punch and didn’t tell people, and some of them went right from the party to the hospital. It was dreadful.”

There is a creepy irony to reading in Timothy Leary’s High Priest how he would scold his daughter that “she’d ruin her eyes” reading in the dimness even as Allen Ginsberg lay upstairs, high on magic mushrooms, choking down his vomit, and experiencing “Milton’s Lucifer” flashing through his mind.

Viva, now the mother of two daughters and journalist in New York, who still says all the sleeping around and drugs she did in the 60’s were fun, adds that this particular period in her life involved “a lot of sexual activity without any real feeling behind it, or real passion. It was all experimentation. I find so much more value in my life right now that I could never go back to it.”

But perhaps the most perceptive comment was made by Rod Gander, now the president of Marlboro College in Vermont. In the late 60’s he was chief of correspondents for Newsweek, and, among other things, he covered the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention and ensuing trouble. “Just the other day a friend of mine was talking to Vernon Jordan,” he begins; Jordan had been the right-hand man to Whitney Young. “And Vernon’s reflection was that during the 60’s we did a hell of a lot of tearing down and ripping away the facade, and left a lot of debris, but that none of us have been able to figure how to clear the debris. And the more I think about it the more I think it’s very apt. Once it was stripped away, we didn’t know how to deal with what was left.”

Leave a Reply