Throughout the 2012 political season, attention was fixed on the contest between President Obama and Mitt Romney. A few other races garnered some media attention, but Americans treated the presidential election as the Super Bowl of politics. The winner, we were told, would chart the nation’s future.

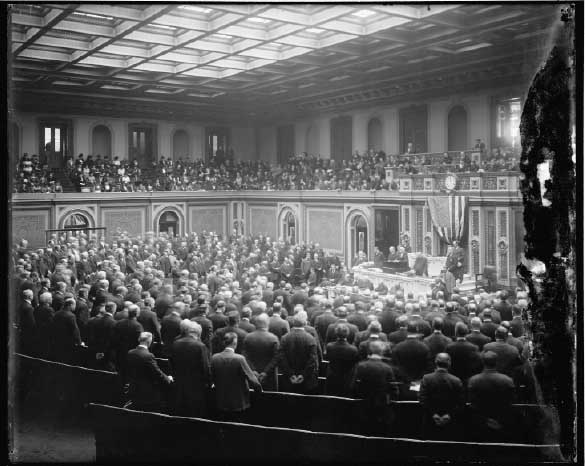

Largely lost in the presidential hype were the biennial elections for the House of Representatives. Every two years Americans trudge to the polls and select a federal representative. These representatives, unlike the president, actually have the power to originate legislation. The president can recommend that certain policies assume legislative form, but without action from a member of the House or Senate nothing will move forward. The president might opine that tax rates should be raised or lowered on a certain class of citizens, but under the Constitution only the House of Representatives can originate revenue bills.

In light of these civics basics, one would think that House races should have dominated the political discussion. But from local diners to talk-radio shows, Americans preferred to chatter about the White House. Incumbency rates are indicative of this indifference to the House of Representatives. Since 1998, the incumbency rate for the House has dipped below 94 percent just once (85 percent in 2010). This has been a steady pattern going back several decades. Despite our crushing national debt and myriad other problems, once a person is elected to the House he enjoys excellent odds of staying there.

The mainstream media certainly bear some of the blame for our fixation on the presidency. Packs of reporters follow the candidates around as they give the same stump speech day after day. Talking heads weigh in each night on the significance of a candidate’s lunch order or his favorite ice-cream flavor. This coverage begins at least a year before the earliest primaries and caucuses actually take place. The hype intensifies with the national conventions and culminates, finally, in election night.

Our apathy for the House races predates the debut of CNN and the 24-hour news cycle, and it has grown as the House’s standing as a representative institution has declined.

Based on the 2010 census, each of the 435 House members is chosen from an average district of 710,767 people. The ratio of one representative for every 710,767 Americans would have shocked the Framers of the Constitution. Under accepted understandings of representation, such a body as our House would have been anathema to the revolutionary generation.

Under Article I, Section 2, “[t]he number of representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand,” and each state is guaranteed at least one representative. This section further provides for a decennial census, after which there is supposed to be a reapportionment of representatives. At the Philadelphia Convention the original number was 40,000 inhabitants for each representative, until George Washington spoke up and expressed his concern that such a ratio was too large to secure “the rights & interests of the people.” The convention quickly addressed this issue, and the Constitution was modified to provide for a smaller ratio of inhabitants to representatives.

At the beginning, there were 65 members of the House. This original number was specified in Article I. It was also short-lived. Following the first scheduled census and the admission of Vermont and Kentucky to the Union, the number of representatives rose to 105 in 1793.

Even with the change won by Washington during the Philadelphia Convention, opponents of the Constitution were concerned that one representative for every 30,000 people was insufficient to foster a truly representative body. They also complained that 1/30,000 was not a constitutional requirement, but the smallest ratio achievable under the Constitution. In the Virginia ratifying convention, George Mason observed that, “[t]o make representation real and actual, the number of representatives ought to be adequate; they ought to mix with the people, think as they think, feel as they feel,—ought to be perfectly amenable to them, and thoroughly acquainted with their interest and condition.” Similarly, the Antifederalist Brutus (likely Robert Yates) observed that, because the people must assent to the laws by which they are governed, their representatives must be the sort of men who would “possess, be disposed, and consequently be qualified to declare the sentiments of the people.” If the representatives lack this connection with the people, Brutus continued, “the people do not govern, but the sovereignty is in a few.”

The simple fact of the people voting, the candidates campaigning, and the winner sharing legal citizenship with his constituents did not amount to true representation. In the Antifederalist view, a representative should be someone who is one of the people. He should worship among his constituents, engage in commerce with them, and socialize with them. He should have similar views and inclinations as his constituents that come from a common upbringing and pattern of life.

Before the first census, Virginia had a population of approximately 747,550 and was allotted ten representatives in the First Congress. This meant that each representative represented 74,755 souls. The Antifederalists saw no way that a representative from such a large body of people could have any real connection with them. The larger and more diverse the body of the people, the more difficult it would be for the representative to share the mind of the people. “[I]t is not but impossible for forty, or thirty thousand people in this country,” wrote the Federal Farmer (likely Melancton Smith), “one time in ten to find a man who can possess similar feelings, views, and interests with themselves.”

In the main, the Federalists did not disagree with the Antifederalist concept of representation, but argued that the Constitution sufficiently guarded a true representation of the people. “It is a sound and important principle,” wrote James Madison in Federalist 56, “that the representative ought to be acquainted with the interests and circumstances of his constituents.” Because the federal government’s powers were few and limited to objects concerning the Union, Madison argued that a larger representation, such as would be needed in a state legislature, was not required.

Madison also expected that the number of representatives would rise above 100 with the first census (which it did) and estimated that the House would have 400 members within 50 years (which it did not—only 242). Madison assured the Antifederalist critics that “the number of representatives will be augmented from time to time in the manner provided by the constitution.” Thus, Madison predicted that, as the population grew, the number of representatives would also increase.

This was the pattern into the 1900’s. After the 1910 census, the number of representatives was increased from 393 to 435. At the time our population was 91 million, and the average district contained almost 210,000 people. After the 1920 census, Congress failed to reapportion the House, which was a violation of the Constitution. In 1929, after much debate and politicking, Congress permanently fixed the number of representatives at 435. The House remains this size today, even though our population has exceeded 300 million.

Not even the staunchest Federalist could argue that the current House adequately represents the people of the United States. This is especially so because Madison’s promise that the national government would have limited authority has proved untrue.

Furthermore, vast districts preclude the people from rubbing shoulders with their congressman and make it less likely that the member can truly identify with his constituents. On average, the winning candidate for a congressional seat in the 2010 election spent $1.6 million. Studies show that the margin of victory is often tied to the challenger’s level of funding. This price of admission precludes all but the richest people from running for Congress. Not surprisingly, 46 percent of House members are millionaires.

Defenders of the arbitrary 435 might concede that the people are not as well represented as they once were, but they contend that significant enlargement of the House would make deliberations unwieldy. Would not a debate involving, say, 800 congressmen be chaos? Such an objection assumes that meaningful debate takes place on the floor of Congress. In reality, most of the work is done in committee. Congressmen appear to vote and then scurry back to their offices. There are unfortunately no more great debates and unparalleled oratory that will be fouled up because of increased membership. Expansion of the House would not affect the committee process significantly.

Moreover, new technologies make the casting of ballots easier and can speed the work of the House, even with increased membership. To the extent opponents cite space concerns, why could not congressmen telecommute, like so much of the workforce does today? With a computer, internet access, and a cell phone, a congressman can work just as easily from his home district as from Babylon.

Opponents also ignore that other countries with representative government have representative bodies larger (and perhaps less dysfunctional) than ours, in addition to more favorable ratios. For example, the 62 million people of the United Kingdom elect 650 members of Parliament—a ratio of 1 per 95,000. Japan’s 127 million people elect 480 members to her representative assembly (1 per 264,000). In Germany, 81 million people elect 620 members to the Bundestag (1 per 130,000). The French National Assembly has 577 members representing 64 million people (1 per 117,636). Americans should be ashamed that so few House members represent such large districts in our country.

Besides simply improving the ratio of citizens to representatives, expansion could have numerous salutary benefits for the health of American democracy. First, it would make it easier for third parties to compete in elections. Under the current state of affairs, congressional races present the people with two options: a Republican and a Democrat. Third parties struggle to raise enough money to reach the 710,767 people in an average district. To campaign effectively in our megadistricts, a candidate needs a sizeable war chest to pay for television and radio advertisements, direct mail, and thousands of unsightly signs. Expanding the House would mean that, in smaller districts, the price of candidacy would drop. A community-sized district would permit alternative candidates to go door-to-door and spread their messages in small meetings. Voters might actually be offered a meaningful choice.

Second, House expansion could reduce the power of lobbyists and special interests. PACs having no connection with a district contribute a significant amount to incumbents. During the 2010 election, each House winner received an average of $665,000 from PACs. It is much more feasible to buy a controlling interest in a majority of a 435-member House than it would be in an 800- or 1,000-member body. The larger the body, the less bang for the buck enjoyed by special-interest groups.

Finally, research shows a correlation between the size of legislative districts and the activities of government. States with bicameral legislatures and small districts for the lower house tend to rank higher on various freedom indices. The larger the average district, the more likely that big-government policies are enacted in the state.

Of course, an assembly can become too big. Madison believed that “the number [in the House] ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude.” He also observed that, “[h]ad every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” This is no doubt true. And yet, while caution and reflection should be used if we expand the House of Representatives, the danger that it might one day become too big is no argument for maintaining a cap of 435.

We could gradually increase the membership and observe the effects on the House’s operation. An initial step might be to increase the number of House members by 215, which would equal the numbers in the British House of Commons. From that point, 100 members could be added after the next census. Hence, after the 2020 census, the House would comprise 750 members. Projections indicate that, by 2020, our population will be roughly 336 million. This means that, with the augmentation suggested, the average congressional district would contain 448,000—smaller than the current districts, but still a far cry from a district that George Washington or the other Founding Fathers would consider appropriate. But it would be a start.

If the House can function with 750 members, perhaps another 250 could be added after the 2030 census to reduce the size of congressional districts further. This would give us an even 1,000. Or, if some critical mass is reached where the House cannot be augmented, but the ratio of members to constituents remains “unrepresentative,” then perhaps we should seriously consider whether Montesquieu was correct when he said that only in a small territory can republican government subsist.

Leave a Reply