At the end of every major period of international strife since at least the Seven Years War, the claim has been put forth that a New World Order has finally arrived that makes possible the substitution of commerce for geopolitics and of law for armaments. This view came into its own after the Napoleonic Wars with the blossoming of “classical” liberal thought. As conservative jurist Sir Henry Maine noted at the time, “War appears to be as old as mankind, but peace is a modern invention.”

In England, James Mill could write that “There is, in the present advanced state of the civilized world, in any country having a good government and a considerable population, so little chance of civil war or foreign invasion, that, in contriving the means of national felicity, but little allowance can be rationally required of it.” Mill would refer any remaining problems to an international court of arbitration. Like nearly all liberals, Mill believed that, while a country could have economic connections anywhere in the world, it had no legitimate political or security concerns outside its own borders.

Jeremy Bentham wanted to replace “offensive and defensive treaties of alliance” with “treaties of commerce and amity,” while, across the Channel, economist J.B. Say argued that “it is not necessary to have ambassadors. This is one of the ancient stupidities which time will do away with.” They should be replaced, he believed, by consuls who would promote free trade. Another Frenchman, Frederic Bastiat, claimed in 1849, only a year after revolutions had shaken nearly every government on the Continent and sparked a number of military interventions, that “I shall not hesitate to vote for disarmament because I do not believe in invasions.”

The liberal dream was repeatedly called into question by a number of wars in 19th-century Europe and by the exploits of worldwide imperialism, and World War I should have dealt it a decisive blow. Yet, in 1933, Norman Angell—whose 1910 best-seller The Great Illusion had declared that economic integration had made a world war impossible—was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in the belief that a second world war could not occur. That was the same year that Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany.

The Republican Party has been vulnerable to similar sophistries because of the excessive influence of classical-liberal economic theory on the modern conservative movement. The United States was not as isolationist during the 1920’s and early 30’s as legend would have it. Republican administrations participated in League of Nations conferences, took the lead in negotiating naval arms-control agreements, and promoted commercial expansion in Asia. The Coolidge administration even negotiated the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, which sought to “outlaw” war itself, proclaiming that “all disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or whatever origin . . . shall never be sought except by pacific means.”

Republican leaders did these things in the belief that a new world was in the making, in which reason would triumph over force. There is very little difference between President Herbert Hoover’s 1929 statement “that the forces of imperial dominion and aggression, of fear and suspicion are dying down; that they are being replaced with the desire for security and peaceful development” and President Bill Clinton’s declaration, 70 years later, that, “perhaps for the first time in history, the world’s leading nations are not engaged in a struggle with each other for security or territory. The world clearly is coming together.” Clinton was speaking just before making a 1999 trip to Asia in which the promotion of trade as a prop for peace was to be a major topic. Hoover, in his speech, also called for the international “interchange of goods and ideas,” with Americans “flung into every corner of the globe,” as a key to a peaceful new era. This was not an expression of isolationism but of liberalism.

The Cold War came so fast upon the heels of World War II that the usual postwar liberal interregnum was cut short. However, the end of the Cold War unleashed pent-up pressures in both academic and business circles. President George H.W. Bush proclaimed a “New World Order,” which was transformed into the concept of “engagement” by the Clinton administration. As Sir Michael Howard noted in his essay The Invention of Peace (2000), “In the last decade of the twentieth century the liberal inheritors of the Enlightenment seemed once again poised to establish peace . . . No alternative model for a world order was on offer; that of Kant and his disciples seemed to have triumphed over all its competitors.”

Classical liberalism also formed the basis of the legalist frame of reference held by the business wing of the GOP, with its desire to subject international relations to the “rule of law” arbitrated by institutions set up by mutual agreement. This faction was particularly vocal during the first half of the 20th century, but its continuing influence can be seen in Republican support for the creation of such institutions as the World Trade Organization and in the abating of denunciations of the United Nations, which had been routine among conservatives a generation ago (though if the United States is unable to garner U.N. support for war against Iraq, hostility may resurface).

At its peak, the phenomenon known as globalization had convinced economists and social scientists across the political spectrum that the nation-state was finished. It was being undermined from within by both business groups and “non-governmental organizations” (NGOs), which were using new modes of global communications to forge their own alliances across borders. And the state’s power to act unilaterally in its own behalf—the crucial “self-help” capability central to realist theory—was being constrained from above by international organizations claiming a higher legitimizing authority and by transnational capital markets that could cripple a state’s finances overnight.

As the 21st century dawned, however, reality began to set in. The dot-com bubble burst, sending “growth” stock prices plummeting and stalling the vaunted information industry, which was supposed to be the driving force of the New Economy. Global financial crises, culminating in the 1997 wave that started on the Pacific Rim and spread to Russia and Latin America, have slowed the world economy. In addition, a wave of corporate-accounting scandals in the United States not only rocked a number of major companies but cast doubt on the claim that business managers were always wiser and more trustworthy than government officials and national leaders.

Far more business ventures fail than states. That healthy societies are able to endure much hardship should indicate a hierarchy of organizational forms that stands in stark contrast to the fashionable claim of the 1990’s that private interest groups should be given priority over national development. Kipling said it best in “The Gods of the Copybook Headings” (1919):

Then the Gods of the Market tumbled, and their smooth-tongued wizards withdrew,

And the hearts of the meanest were humbled and began to believe it was true

That All is not Gold that Glitters, and Two and Two make Four

And the Gods of the Copybook Headings limped up to explain it once more.

And then there were the terrorist attacks of September 11. The core of the realist critique of liberalism was provided by E.H. Carr: “Potential war . . . [is] a dominant factor in international politics.” It has always been the most important factor in the program of economic nationalism. Liberals have focused on Adam Smith’s theory of the benefits of free trade and have taken that theory to an extreme in the subsequent development of the idea of “comparative advantage.” Realists have understood why Smith called his classic work The Wealth of Nations. In his pioneering vision of the Industrial Revolution, Smith argued that domestic production capacity, not trade, was the basis for real national progress. Trade could support economic growth, but not all patterns of trade did so. Trade is not always a zero-sum game, and its composition can affect strategic industries. And the way that the benefits of trade (and investment) are distributed among economic partners can affect the international balance of power.

Consider the top U.S. objective at the World Trade Organization, which was the opening of world agricultural markets to American exports. This American initiative ran into a wall at both the 1999 Seattle and 2001 Doha ministerial conferences. The issue is framed by the rest of the world as “food security.” No country worth its salt wants to be dependent on imports for something as vital as its food supply.

In a speech to the Future Farmers of America last July, President Bush himself argued for “food security,” asking,

how do we make sure American agriculture thrives as we head into the 21st century[?] I mean, after all, we’re talking about national security. It’s important for our nation to grow foodstuffs, to feed our people. Can you imagine a country that was unable to grow enough food to feed the people? It would be a nation that would be subject to international pressure. It would be a nation at risk.

This is exactly the way the leaders of China, Japan, India and the European Union feel when Washington tells them they should drop subsidies for their farmers and trust imports from the United States and a few other countries (Australia, Canada, Brazil) for their survival. They are simply not going to do this. Indeed, the United States has given them an example not to follow. In the 1980’s, Iraq substituted food imports for domestic production, with much of the trade financed by the United States. Then the post-Gulf War economic sanctions cut off this trade, sending Iraq into a severe nutritional crisis that has cost tens of thousands of lives.

China has proclaimed self-sufficiency in food production as its official policy. She has also adopted other industrial policies in the name of national security. A U.S. Government Accounting Office report released in April 2002 confirms that Beijing is not embracing the concepts of disintegrated production and interdependence that are popular in American circles: “China’s stated goal is to become self-sufficient in the production of semiconductors for its domestic market and to develop technology that is competitive on the world market. This goal is being pursued for economic and national security reasons . . . ”

Beijing never adopted the post-Cold War view of a harmonious world upon which corporate globalism was based. A Chinese Defense White Paper published in October 2000 argued that,

in today’s world, factors that may cause instability and uncertainty have markedly increased. The world is far from peaceful. . . . Hegemonism and power politics still exist and are developing further in the international political, economic and security spheres. . . . As modern science and technology and economic globalization continue to develop, competition among countries has become fiercer than ever before.

This stands in stark contrast to how the world is presented in the 2002 National Security Strategy of the United States (NSS). The NSS chapter on international economics argues that “A strong world economy enhances our national security by advancing prosperity and freedom in the rest of the world. . . . We will promote economic growth and economic freedom beyond America’s shores.” Regional conflicts, terrorism, rogue states, and “weapons of mass destruction” figure prominently in the rest of the NSS, but there is no hint of any rivalry or threat to the balance of power from the economic gains made by other countries. Earlier, the NSS quotes from a speech President Bush gave at West Point: “the gravest danger to freedom lies at the crossroads of radicalism and technology.” Yet there is no connection drawn between economic and military capability in the chapter that should have been devoted to the topic.

The GAO did draw such a connection in its report, finding that “China’s efforts to improve its semiconductor manufacturing capability have narrowed the gap between U.S. and Chinese semiconductor manufacturing technology from between 7 to 10 years to 2 years or less”; this rapid progress “has improved its ability to develop more capable weapons systems and advanced consumer electronics.”

From Singapore to Tokyo, alarm bells have been sounding about Beijing’s drive to become the “production center of the world.” China’s main threat to Japan is in electronics, a mainstay of the latter country’s economy. Several Japanese electronics giants (including Toshiba Corp., Sony Corp., Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., and Canon Inc.) have announced plans to expand operations in China, even as the industry is shedding tens of thousands of workers at home. Analysts at Salomon Smith Barney calculate that, if current growth rates continue, China’s high-tech exports will overtake Japan’s within the decade.

China’s competitive reach extends beyond Asia. Mexicans today are raising the same concerns about China that opponents of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) made a decade ago about Mexico. Mexico was the last holdout against China’s entry into the WTO because of fears that China’s meager prevailing wage would lure manufacturing jobs from Mexico. Mexican wages for workers in the maquiladora sector range from about $2.00 to $2.50 per hour, including some benefits and labor taxes. Figures on Chinese labor costs are less reliable but range from 35 cents to as much as one dollar per hour if all benefits and taxes are paid. By last spring, the maquiladora industry, which had been created to marry U.S. capital with Mexican labor, had lost 287,000 jobs since its October 2000 peak, a 21-percent drop. Not all of these jobs went to China, but a good many did.

When the Dutch firm Royal Philips Electronics closed its PC monitor plant in Ciudad Juárez and shifted operations to its plant in Suzhou, China, it cited China’s more competitive supplier base as the reason. China’s advantage was summed up by Prof. Robert S. Ross of Boston College: “China, unlike Japan, has the natural resources to sustain economic development and strategic autonomy. . . . Rather than move abroad as labor costs increase . . . Chinese enterprises, following market forces, will be able to move further into China’s interior to exploit an inexhaustible, inexpensive and relatively reliable labor force.” Business plans for foreign companies operating in China focus on local production both to supply the Chinese market and to export. This process will not only strengthen China but weaken Beijing’s economic rivals in Asia, many of whom are political and military allies of the United States.

As American firms expand their operations in China, they want a better trained workforce available to meet their staffing needs. Honeywell Aerospace, for example, provides extensive training for the “best engineers” working for Aviation Industries of China (AVIC), including bringing them to U.S. plants to learn about American technology firsthand. AVIC is the state enterprise responsible for developing and manufacturing both military and civilian aircraft, missiles, and engines. It also conducts extensive research in aerodynamics, materials, and manufacturing technology.

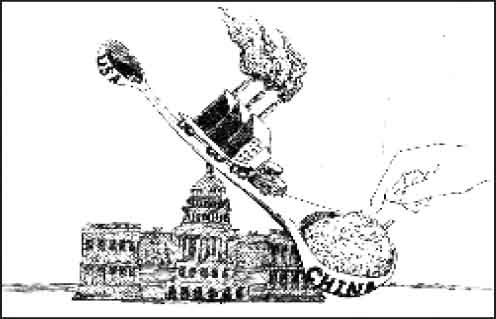

Last summer, the U.S.-China Security Review Commission released its first annual report on the implications of American aid to Chinese economic development. The commission was created by an act of Congress, and its 12 private-sector members were appointed on an equal basis by Republican and Democratic congressional leaders. The commission found “the U.S. has been a major contributor, through trade and investment, to China’s rise as an economic power” and that “over the next 10 years China will acquire a modernized industrial capacity to build advanced conventional and strategic weapons.” It also found that Beijing’s elite believe that China’s rise will parallel America’s decline.

If Beijing’s ambitions are to be thwarted, the American elite must also remember that nation-states count, even in a globalized economy. Where investments are made, where factories are located, where resources are developed, and where research is conducted determine both the prosperity and the security of a country’s citizens. The workings of the world economy are very uneven in their effects. The “invisible hand” of classical liberalism does not wave the flag of any particular country, and transnational corporations cannot be expected to put the larger interests of any national community ahead of their own narrow self-interests—unless instructed to do so by sovereign authorities on behalf of those who do still wave flags.

September 11 reminded us not only of the dangerous nature of the outside world but of the innate patriotism still felt by most Americans. No one rushed to hoist corporate banners in their front yards or to slap decals of corporate logos on their cars; it was the Stars and Stripes that appeared everywhere. In the heightened pace of international politics in the days since, it has become apparent that people around the world still owe their primary allegiance to local communities or other independent groupings based on feelings of identity far deeper than those invoked by shoes or DVD players. As British psychologist Alan Branthwaite has put it, “people want to live their lives with others who they feel are similar and they can trust . . . in a place under their own control, to exercise their rights and pursue their goals.” It is the duty of statesmen to formulate their policies accordingly, channeling economic forces in ways that strengthen national capabilities in a divided world.

Leave a Reply