The featured theme of this month’s magazine is focused on a particular task, namely retrieving conservativism and conservative thinkers from the past and explaining their continued relevance to the present. The current conservative movement, as a form of media entertainment and as a partisan PR machine, has undergone sweeping change in just about every respect since the mid- and certainly early-20th century. Equally obvious has been the tendency to hurl into a bottomless memory hole provocative past thinkers, such as Southern traditionalists, localists, and military noninterventionists. Other thinkers have suffered an even more ignominious fate at the hands of Conservatism, Inc., by being transmogrified in such a way that they offer no challenge to current “conservative” agendas or media celebrities.

Presenting our subjects as people who can still teach us about their “hijacked” worldviews (a phrase used by Pedro Gonzalez in his piece later in this issue) and about what the right should look like, is a difficult task. First of all, we the interpreters have to save these subjects from an appearance of irrelevance and, in some cases, from efforts that have been undertaken to render them acceptable to present standards of sensitivity. Moreover, those introducing their subjects to a younger generation of self-identified conservatives or simply to curious readers of a later generation cannot take for granted a continuity of thought leading from an older tradition down to its current representation. The transformation of the movement has been so complete that what goes by the name “conservative” is often no more than the proclamation of leftist positions that the left has now abandoned for even more radical ones.

One is reminded in this instance of the caustic definition of “conservatism” made by the Southern divine Robert Lewis Dabney in the second half of the 19th century:

…[A] party which never conserves anything. Its history has been that it demurs to each aggression of the progressive party, and aims to save its credit by a respectable growling, but always acquiesces in the innovation. What was the resisted novelty of yesterday is today one of the accepted principles of conservatism.

Dabney was ridiculing what he took to be the party of “Northern conservatives,” whom he believed were gulling his fellow Southerners and who he thought were out to advance their own careers while lining their pockets. These Northerners were transparently lying pols who claimed to be what they were not.

Today, faux conservatives are a more serious threat to the right than they were in Dabney’s day. They steal the right’s identity by rewriting its history and enshrining “the resisted novelty of yesterday.” They throw out narratives that no longer fit their desired image or satisfy the tastes of their donors. They also throw out empty rhetorical references to “values” and “principles” that they attribute to conservative thinkers whose real views they shy away from, lest they alienate patrons. Whether we are talking about disquieting thinkers being thrown into a memory hole or being reduced to innocuous objects of celebration, those who suffer either ignominy need to be made once again fitting subjects of discussion. That is what the contributors to this series will try to do.

The work of our contributors to this “Remembering” series reminds me of the idea of anamnesis as presented in Plato’s Meno and Phaedo. In Plato’s theory of knowledge, as expounded by Socrates, what we learn is considered to anamneston—that which is recollected from a previous existence. There is nothing we can learn conceptually that we didn’t previously know, but forgot until a wise teacher, like a midwife, drew it from our minds, or perhaps our subconscious. In a not totally dissimilar way, our contributors may bring back some distant memory of what true conservatives of the past actually said and thought to serve as a guide for the present and as a stimulant for new thought.

Young conservative readers have told me how they discovered almost by accident some of the thinkers we’ll discuss. They were looking through histories of the conservative movement and came across the critical thought of authors whom they decided were worth exploring. They had heard of them before, somewhere, but were not sure that they remained relevant to our own troubled, morally discombobulated times. This represented a modified form of anamnesis, even if we are not speaking here about something extracted from a previous incarnation. Rather we are describing the remembrance of thinkers who once influenced the intellectual right but whose memories have faded, because they ceased to be useful to Conservatism, Inc. In some cases these figures continue to be favorably mentioned, but only as empty icons whose ideas, once predigested, can no longer harm conservative media enterprises.

A final point should be emphasized in this note on the sketches that follow in this and future issues. Some of our featured thinkers fought furiously with each other. Frank Meyer quarreled incessantly with almost everyone else at National Review throughout his career there. James Burnham, a sedate family man as well as a brilliant political analyst, couldn’t wait to leave the company of his coworkers in order to escape the din caused by Meyer’s pugnacious encounters. Some of these confrontations between conservative titans took more measured form, in published debates in which the combatants were allowed to take positions that would no longer be permissible in any establishment conservative newspaper or magazine.

Further, those who engaged in these spirited discussions never got rich by doing so. Most spent their lives in very modest circumstances and would have been morally outraged if they had learned of the obscene salaries collected by today’s Fox News celebrities and “conservative” think tank executives. I’m reminded of the small garden apartment, stacked with dusty books, inhabited by a mentor, Will Herberg, who had once been the National Review religion editor. Will would not have known what to do with all the money lavished on our “conservative stars” for defending the GOP and for reiterating old leftist positions. This brings me back to why Conservatism, Inc., has become intolerant as well as tiresome. It is running a very big business that depends on patrons with narrow interests. These patrons and the party-line consumers really couldn’t care less about what the Southern Agrarians thought about modernity or what Robert Nisbet concluded about mass society (meaning the one that we exist in right now). We at Chronicles hope to make up for this deficiency, starting with this recurrent feature series, “Remembering the Right.”

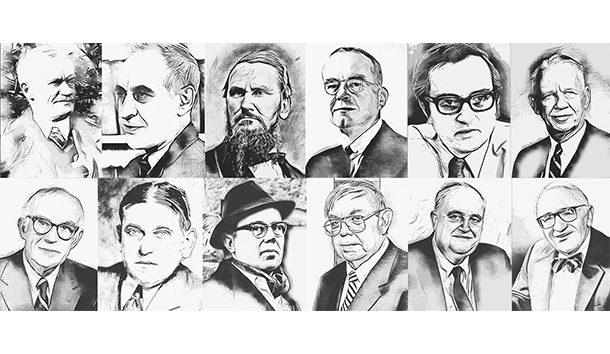

Image Credit: above: (left to right) Albert J. Nock, Frank Meyer, R. L. Dabney, James Burnham, Eugene Genovese, Willmoore Kendall, Robert Nisbet, H. L. Mencken, Russell Kirk, Samuel Francis, M. E. Bradford, Murray Rothbard

Leave a Reply