A virtue of America’s quadrennial election cycle is its success in revealing and giving form to whatever popular malaise has set in over the past four years, whether the results of the elections themselves address the disorder or not, and occasionally in raising real issues, even if only by implication. In this respect, the presidential election of 2016 so far has been more significant than recent ones have been.

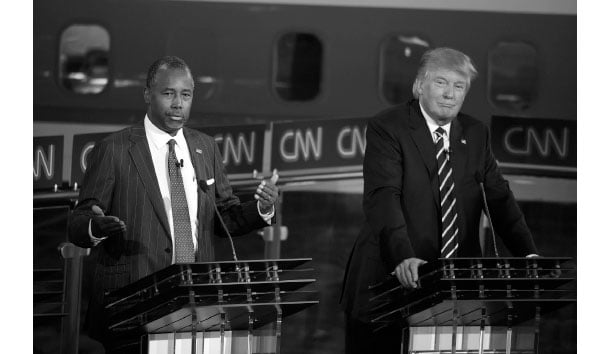

No one doubts the depth and breadth of popular discontent in this country, which appears to be attaining critical mass. Democrats put this down to economic inequality and to a Republican Congress stonewalling the White House by refusing to act on legislation Democrats want passed; Republicans, to the Democrats’ determination to transform America morally, socially, and demographically and to President Obama’s Caesarism in resorting to executive action when he finds himself thwarted politically. Both parties are agreed that the electorate’s enthusiasm for presidential candidates from beyond the circle of professional politicians—like Donald Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina—on the Republican side, and maverick politicians like Bernie Sanders on the Democratic one, signals the voters’ lack of trust in their incumbent representatives personally and the political establishment in general.

This explanation, while true so far as it goes, fails to account for the unease, suspicion, frustration, genuine anger, and behind them the dim fearfulness of the American public. It is the kind of fear produced by the smell of danger without danger’s outlines coming in sight, the sense of a threat unidentified. The pollsters report that Americans believe their country is in decline, her best years behind her. Economic insecurity and moral confusion in a relativistic age contribute to this impression. So does an awareness of civic impotence that is part of the concern with the perceived untrustworthiness of the political class—its fundamental dishonesty and the betrayal of the public by men and women in control of every major American institution whose democratic pretense to “transparency” and “accountability” only points up their determination to use their power and influence to have their own way with the country, come hell or high water.

The most significant accomplishment in the history of Western civilization is not the creation of free institutions, representative government, and democracy. It is not the rise of a capitalist economy and the free market. It is not the establishment of free inquiry and the discoveries of modern science credited with leading Europeans out of the age of blind superstition, ignorance, and enslavement by nature and by priests. It is not the sequence of causal events in economics and technology that produced the Industrial Revolution and the material revolution, the explosion of affluence and of physical well-being that industrialism made possible. The West’s most significant accomplishment is the creation of Power as a response to the impulse Augustine called the libido dominandi—the lust for Power for its own sake, for domination, and for control, valued by moderns even above its innumerable practical uses and benefits.

Power in this sense—collective, diffuse, impersonal, and omnipresent, settling like a fog over every institution, every area of human activity, every social association, resting finally upon thought itself—is a phenomenon of the modern West and increasingly the whole of the modern world. Power and the relationships of power are as old as humanity itself, but power in the sense of the traditional idea of the thing is something very different from Power in its contemporary meaning. When we speak of Nebuchadnezzar as having had power, or Caesar, or Charlemagne, or Henry VIII, or Robespierre, we mean personal power wielded in societies and operating among rival personalities and groups, and valued indeed for its being personal—limited to the reach of the powerful and their circle. Power of the personal sort exists today, of course, and always will—else the Republicans would be fielding no candidates at all this season, instead of the 16 or 17 with whom their presidential race began. But in the modern industrial and postindustrial world, personal power, even at the apex of power, is—despite ceremonial appearances—almost unidentifiable among the vast impersonal and largely unaccountable powers inherent in modern and postmodern political, bureaucratic, administrative, economic, legal, educational, scientific, and social institutions. Though the leader of a nuclear-armed country may choose to incinerate the world at the touch of a button, the power to do so does not reside in his capacity as a particular man but in a convergence of institutional powers that finally constrains personal power to two unimaginably catastrophic choices—wholly unlike the regal authority that dispatched an English army, led by Henry V himself, across the Channel to engage the French at Agincourt 600 years ago this fall. The ultimate power of the man in the Oval Office or the Kremlin is one no morally sane person would relish in the crisis—he might even regret having sought it in the first place—but the Power that created the hydrogen bomb is something Western man deliberately willed for himself. It is the ultimate example of personal power—authority—displaced by Power.

The modern world rests on science and democracy, but the two things are essentially incompatible. Knowledge is power, as Francis Bacon said, and democracy is said to be freedom. Yet people are not equally capable of knowledge, something naturally reserved to the few, while Western science is unimaginably powerful—hence undemocratic. A regime, in the Latin sense of the word, that is dominated by science is necessarily a regime created and governed by elites. But Americans want the benefits of modern science and 18th-century republican freedoms, and the insurgent wing of the Republican Party today demands them. It is obvious that they, and we, cannot have both. Liberalism and communism have always assumed that the two goods could be reconciled (though neither understands freedom in the 18th-century meaning of the word) by state planning and state ownership of production. But communist regimes have ended in political, economic, cultural, and human catastrophe, and liberal ones are going in the same direction, though far less brutally.

The Western project since the Renaissance has been to “vex” nature, as Bacon put it, in order to understand her, and to understand her in order to enlist her in the service of men. What had been the primary purpose of “philosophy,” to study God’s works as a means of apprehending and giving greater glory to Him, became secondary as modern science advanced, until early in the 18th century it was abandoned entirely. Since then, the goal of science has been the domination and control of nature in order to exploit her. That aim has been realized far beyond Bacon’s wildest possible imaginings, and even those of 19th- and early 20th-century scientists. According to Scripture, the world was made for man to work and develop by the sweat of his brow. It is only right and just that men should harness nature to serve their needs. But as God faded as a presence from behind scientific investigation and enterprise, man took His place in his self-estimation and in his own ambition, which aspired increasingly to a Power that would rival divine omnipotence and make God irrelevant. But Power means control, and man’s power over nature implies man’s power over men as well. Before Power stepped in between nature and man, men were ruled chiefly by the powers of nature; since that time they have been ruled mainly by men and the works of men. This is partly from necessity, but it is also because people who like to control things like to control other people—where there is a need for such control, and where there isn’t.

In the second half of the 19th century the new and unprecedentedly powerful industrialism that was revolutionizing Western societies provoked a counterrevolution on both the right and the left that aimed to control and direct industrial capitalism by political action designed to address industrialism’s social, economic, environmental, and political consequences. This counterrevolution had only limited success, but in that era the effort to tame the mechanical Leviathan seemed feasible, giving reformers a sense of assurance and confidence in a still-manageable world. A century and a half later the postindustrial world, having become unintelligible to most people in theory and in practice and seemingly uncontrollable by the private entrepreneurs who own and operate it and the governmental functionaries attempting to regulate it, offers scant cause for similar confidence. The artificial world man has created for himself has reached an extent and an opaque complexity that rival, in their unintelligibility, the natural world before Western science began to investigate it and that have provoked in postindustrial men a fear and apprehension analogous to the primeval human fear of nature. Yet neither the science nor the political system that could rescue them from the state of postnature is evident anywhere.

Modern science has created a world difficult for most people to fathom, and too complex for politicians and administrators to manage, assuming they themselves have understood it—a very questionable assumption. Unbridled advancement in scientific technique, and the mass democracy that technology has helped make possible, simply do not agree with each other.

Science and the fruits of science, technology and its political, economic, social, and environmental consequences, are more easily and conveniently managed, without popular intrusion, by administrators than by politicians. Owing to this, and to the vast bureaucratic apparatus set in place by advanced liberal states, Western political systems are being steadily depoliticized and deprived of the means of self-control by the loss of the capacity for political action, in the United States as in the European Union, where the subject has been a major issue for intellectual and political debate for some time now. Of all Power’s forms, diffuse power is the hardest to resist, making resistance appear hopeless to frustrated and angry citizens. Critics who deplore the “polarization” of American political life do not see what is actually going on: The insurgent wing of the GOP is seeking to repoliticize American politics against the wishes of the Democratic-Republicans (or Social Republicans) and the Democratic Party, all of whom are more than happy with a system dominated by administrators, lawyers, and judges, a system in which executive order is exercised when and where needed to correct democratic political action, or fill in for it. John Boehner, who has been pushing “comprehensive immigration reform” for years, was not merely relieved by President Obama’s executive action granting amnesty to more than four million illegal aliens that Congress had refused to pass on numerous occasions; he is reported to have encouraged it by a promise to the President not to oppose the flagrantly unconstitutional order Obama had for years protested he was constitutionally prohibited from issuing.

People running for political office either have confidence in their ability to operate effectively in an increasingly incomprehensible and uncontrollable world, a world of Power diffused across hundreds or even thousands of administrative institutions and agencies staffed by bureaucrats, or are able to manage a convincing show of confidence. Many, in any event, care little or nothing about accomplishing anything of significance, so long as they can enjoy the “powers” and perquisites of office—probably the case with the majority of office-seekers. The voters they hope to convince aren’t so sure. Indeed, they have pretty much decided to the contrary regarding the claims and pretensions of professional politicos. The preference of today’s electorate for candidates with no political experience is analogous to the eagerness of the big commercial publishers for “debut” novelists who, lacking a track record, can be touted before pub date as blooming geniuses and potential bestselling authors. It also reflects Americans’ misapprehension of the contemporary political system. Where Power is impersonalized by institutions and regulations, and where personal authority is largely absent, politics is reduced to show biz—the smoke-and-mirrors routine at which Barack Obama has excelled throughout his career—and illegal fiat, also a specialty of the President’s. (The huge and unfortunate exception to this rule is the U.S. Supreme Court.) Where the rule of bureaucracy prevails in a society overdeveloped in almost every respect to the point where it is swamped by problems and confusions undreamt of by previous generations down to the last two or three, that society becomes unmanageable, and its impatient and angry citizens increasingly ungovernable—an accurate description of the Western nations in the 21st century. In these circumstances it is probably of little real importance which political candidates Americans elect to office, so long as they aren’t Caligulas, Lincolns, and Stalins, since, whoever they are, they are certain to find themselves submerged in their intractable, incomprehensible, and impossible jobs, as the rest of us are being submerged in the new creation of our own making.

Leave a Reply