I was fortunate to grow up before the Immigration Act of 1965 began an incremental and insidious change in the ethnic composition of America. I had friends whose parents were immigrants. I thought nothing much of it because the parents had all come from countries in Northern or Western Europe and almost immediately became indistinguishable from other residents of our little community of Pacific Palisades. With the exception of a Chinese family, the 8,000 or so residents of the Palisades were white. Moreover, with the exception of a few Jewish families, Palisadians were uniformly Christian. Everything closed on Sunday, and nearly everyone went to church—it was only a matter of which one. There were Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Christian Scientists, and Catholics aplenty.

The immigrant parents I spent the most time with were Peter and Pat Kinnell. They were different in only one way. They insisted that all of us kids call them by their first names. This stunned me at first because we addressed all other parents as Mr. or Mrs. The first-name address did not mean, though, that proper manners and decorum were not observed. In what we called “strictness” the Kinnells were definitely not lax. An incident on their back patio left an indelible impression on me. Chris Kinnell and I were about ten, and Chris’s kid brother, Patrick, was seven but big for his age. Pat had made us sandwiches, and we were chowing down when Chris and Patrick got into a tussle. In the scuffle, they knocked their sandwiches from the patio table onto the concrete patio deck, which had puddles of water after a recent rain.

Hearing the commotion, Pat came out of the house. She waited until the boys had wrestled themselves into exhaustion and then had them retrieve their water-soaked sandwiches, which now also had a dusting of dirt and sand. She then ordered Chris and Patrick to eat the sandwiches—to the very last bite. The Irish-born Pat had been reared in County Down during the 1920’s and 30’s. Food was not to be wasted. My mother was the same way. When I went into the Marines and saw the line on the mess hall wall, “Take All You Want But Eat All You Take,” it was nothing new to me. Now, in the Kinnell’s backyard, I watched as Chris and Patrick slowly and dutifully masticated their soaked sandwiches and grimaced as they ground particles of sand between their teeth. Their sad and resigned expressions reminded me of the Laurel & Hardy episode in which a ship captain’s, a dead ringer for Wolf Larsen, forced Stan and Ollie to eat a meal the boys had prepared for the thug, substituting the cords of a mop for spaghetti. It was all I could do to keep from bursting out laughing. I had no desire to have the wrath of Pat turned on me.

Pat had dark hair, sparkling eyes, fair skin, and rosy cheeks. She wore her hair short, had a slim athletic figure, and looked like a cute teenage girl. She was something of a tomboy. She could play sports with us and throw a ball like a guy. When she got angry, her brogue became more pronounced. I thought Chris and Pat had a “really neat mom.” I thought the same about their father, Peter, English-born but of Scottish ancestry. He had been a crack cricket player and immigrated to the United States in time to serve in the Army Signal Corps during World War II. Coincidentally, he was stationed back in England during the war. He was a tall, lanky fellow who wore thick-lensed glasses. By the time I met him he was an engineer, as were many fathers in the Palisades during that era, working in the aircraft/aerospace industry.

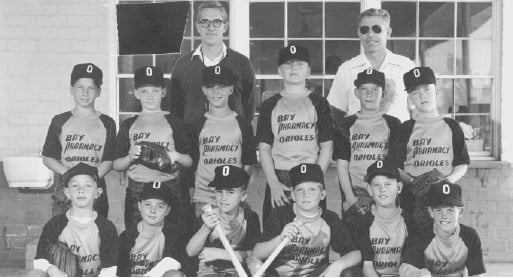

Peter became the head coach of our Little League baseball team, the Bay Pharmacy Orioles. He was indistinguishable from the league’s other coaches, although he often did not bother to don a glove when playing catch with us younger players, who could not yet throw very hard. I remember when he warmed me up to pitch for my first time. I was nine. Peter didn’t bother to grab a glove, let alone a catcher’s mitt. I hesitated to let go with a fastball. He reassured me, “Don’t worry. We were barehanded in cricket.” He would also occasionally exclaim, “Good show!” We got used to that particular phrase because another parent also employed it regularly, especially after a shot or two of whiskey. The parent was David Niven. The famous actor and English immigrant would arrive at our games, attaché case in hand. He’d find a seat in the grandstands and open the case, which turned into a miniature bar. Drinks were on David. Some parents must have frowned on the practice, but not fellow actors Jim Arness or Cameron Mitchell, who also had sons on the team. By the fifth inning of our seven-inning games the three actors were our most vociferous rooters.

By the time I was playing baseball my father had died. Dads are important for Little League players, not only to coach their sons in the required skills but to protect them from parents who envy the abilities of players who compete with their own sons. One of our assistant coaches considered me, without a dad, fair game. The less playing time I had, the more his own son would have. The better I performed, the less he liked it. He did everything he could to undermine my confidence, and confidence is everything when trying to hit a baseball or field a hot grounder. The assistant coach finally became so obvious in his dastardly designs that Peter saw what was happening and came to my rescue. I don’t know what words were exchanged, but the assistant coach had a change of attitude. He didn’t become my supporter or help me in any way, but he no longer harassed me or undermined everything I did. By the time I was 17 and had grown muscles to match my temper, he had moved from the Palisades. It was probably just as well. I got in enough trouble for fighting without adding him to the list.

Peter and Pat Kinnell were not exactly a second set of parents for me, but they could have been. Peter would not have long to live. He died from cancer when Chris and I were 16. Chris was devastated. Pat wasn’t much better. By that time the family included a little sister, an adorable towhead. I remember Pat talking with my mother about going on with life and rearing children after the loss of a husband.

Our relationship was possible because the Kinnells were, broadly speaking, kinfolk. We shared nearly everything in common. Sleeping over at their house was like sleeping at my own house. If the ages were adjusted, I could have married Chris’s and Patrick’s sister and produced children who looked like simply more family. Either of the Kinnell boys could have married my sister and produced children who looked like simply more family. Flash childhood photos of the McGrath or Kinnell kids across international cyberspace, and people would have, once upon a time, identified us as typical American kids.

None of this would have been possible had the Kinnells been Somali, Iraqi, or Indonesian Muslims, or Indian Hindus, or Chinese Taoists, or Congolese animists, or anything other than what the Kinnells were. The arrival of the Kinnells on these shores reinforced the European racial stock and the cultural and religious traditions of America. Immigration law from the 1920’s until 1965 ensured that the great bulk of immigrants would do exactly what the Kinnells had done. The Immigration Act of 1965 changed all that—and changed it without the approval of the great majority of Americans. The majority of legal immigrants now are nonwhite and non-Christian, and a million of them arrive every year. Who asked for this? Who asked for the racial and religious transformation of our country? Can you imagine the Japanese or Chinese, for example, enacting an immigration policy that would cause them to disappear as a people and a culture?

One of the first consequences I saw of the Immigration Act of 1965 was the end of an American institution of the Fabulous Fifties, the gas station. In my small town there were several gas stations, and each one was a hangout for a different set of guys. Among other gas stations were Darling’s 76, Robinson’s Mobil, Hall’s Chevron, and Lance’s Richfield. The surnames of the owners tell you much of what you need to know. Check who owns your local gas stations today. If conditions are similar to those in Southern California, then I’ll bet the names are Arab or Iranian or, perhaps, Indian.

The gas station closest to my family’s house in the Palisades was George Lance’s Richfield on the corner of Monument Street and Sunset Boulevard. I hung out there to watch my older brother, Dave, and the other “big guys” work on their cars. The chief mechanic at Lance’s was an old ruddy-faced, bald, chain-smoking character named Perkins, known to all as Perk. I’m not sure if I ever saw him entirely sober. Tucked away in a storeroom was a bottle of whiskey that he nipped throughout the day.

Cars were simple then and engine compartments roomy. With a good set of tools and good guidance almost anyone could work on them. Hanging out at a gas station was a rite of passage for boys in the 50’s. It was an all-male environment. This was a special treat for a young kid. The adult men at the station smoked, drank, and, after busting their knuckles when the wrench slipped, swore. I remember when tall, very lean, and often half-inebriated Bob Weber let loose with a “Jesus Christ!” I thought that I had heard the very worst epithet yet in my young life.

Gas stations also provided teenage guys with jobs pumping gas, cleaning tools and washing down work areas, and turning wrenches as apprentice mechanics. The teenage apprentice mechanic at Lance’s Richfield was Jack McGinity, who lived only a block up Monument. Jack was lean, wiry, and handsome and combed his hair back on his head in a perfect 50’s style. Think of a young Dennis Quaid. Jack not only had looks but also bitchin’ cars, including a ’40 Ford. He also had a good-looking girlfriend, Nancy Sinatra. The guys use to kid Jack that if he got her pregnant Frank would send a couple of goombahs to break his legs—or worse. Jack recently told me it wasn’t that way at all, that Frank was so wrapped up in his career and out of town so often that he wasn’t much of a factor. Frank was responsible for Nancy’s ’57 T-Bird, though. He had gotten the car for doing an ad for Ford and gave it to Nancy. Jack put a supercharger on it and had it repainted candy-apple maroon. It was often sitting on the corner of the gas station lot facing Sunset and looking absolutely cherry.

A hot rod or a custom motorcycle sitting on the corner of a gas station lot was a calling card for the station, the signature of a young mechanic, or evidence of who was hanging out at the station. Driving through the Palisades on a typical weekday one might see Merritt Dailey’s ’37 knucklehead burgundy and chrome Harley chopper with peanut tank, suicide clutch, and jockey shift; Scott Turnham’s ’52 Olds Fastback with an engine built by Jerry Unser; Steve Aaberg’s ’32 Ford pickup with a V-8, twin carbs, and a beer keg for a gas tank; Danny O’Mahoney’s ’49 chopped, 2-door, bathtub Merc with spinner hubcaps and leg pipes; and several others. No self-respecting teenager had a car that was entirely stock, and everyone worked on their own machines.

Several of the gas stations closest to where I now live in Thousand Oaks are owned by Arabs or Iranians. I would not be surprised to learn that Near and Middle Easterners own the majority of the stations in Thousand Oaks. When these folks immigrate here, they automatically become eligible for Small Business Administration low-interest loans—all, of course, courtesy of the American taxpayer. As “immigrants” and “minorities” they are given priority for the loans and nearly always receive them. (Try getting one as an American white male.) By the 1970’s Arabs and Iranians were gobbling up gas stations. This was the beginning of the end for the old down-home neighborhood gas station. I doubt many people know the owner of the station where they pump their gas today.

About the same time it was deemed more efficient to separate the air and water hoses from the gas-pump islands. Now, after fueling, you had to move your vehicle to a second location to fill your tires or radiator. I understand this moved people through the gas pumps more quickly and had nothing to do with the immigrants. However, the immigrant-owned stations were quick to erect coin-operated machines and charge the customer to activate the air compressor. The charge was initially a quarter but quickly rose to 75 cents. Charging for air outraged most Californians, who had long been accustomed to filling their tires for free. A little more than a decade ago the California legislature finally took some action, passing a law requiring gas stations to provide air and water for free to customers who purchased any amount of gas.

Ever since then I’ve noticed that most of the immigrant-owned stations do not inform their customers that air and water are free, and the coin-operated machines are still in place. If you are an informed Californian, you ask whoever is operating the station to start the compressor or give you tokens for the machine. If you are one of the many, perhaps most, of the Californians who do not know of the law, or if you have arrived from another state, you will be tricked into unnecessarily paying 75 cents. That’s not a lot of money, but it’s the conniving and cheating of these station owners that get my dander up. They feel no shame in deceiving you, only a smug satisfaction for having gotten away with it. Most of the immigrant-owned stations only pump gas and sell chips and soda. The garage with two or three lifts and as many mechanics that was always a part of the older stations is, for the most part, long gone. There is no longer a group of kids hanging out at these stations, learning how to torque head bolts or change tires.

A piece of Americana has disappeared with the demise of the old gas stations and the culture that surrounded them. More significant, though, has been the flow of immigrants into the United States from countries such as Iraq, Iran, India, China, Korea, Cambodia, Vietnam, Nigeria, and Somalia. El Cajon, 15 miles east of San Diego, is now second only to Detroit in numbers of Iraqis. More than 300 arrive in El Cajon each month. Signs on many storefronts are now in Arabic. The town is becoming known as Little Baghdad. San Francisco now has a Chinese mayor and a population that is one third Chinese. Four of the members of the Board of Supervisors are Chinese, as is the assessor-recorder, the public defender, and the county’s state senator. Across the bay, Oakland also has a Chinese mayor, and its Chinese population is approaching 20 percent. Once nearly lily white, Long Beach had so many Iowans settle there that an annual Iowa Day picnic was the city’s greatest event. Today, the city of a half-million people is less than 30-percent white and has the largest population of Cambodians in the United States and the second largest outside of Cambodia. The Cambodian neighborhood along Anaheim Street is known as Little Phnom Penh. So it goes throughout California, all thanks to the Immigration Act of 1965.

None of these people is necessarily bad, and many are productive and enterprising, but they are entirely different tribes from the Celtic and Germanic folk who made America. Arabs, Asians, and Africans will not become the Americans of Norman Rockwell illustrations. Nor do they feel any affinity for the pioneer migrations through the Cumberland Gap, the Pennsylvania riflemen at the Battle of Saratoga, the suffering of the soldiers at Valley Forge, the debates of the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention, the farmers settling the Ohio Valley, the Mountain Men trapping the Rockies, the Alamo, the sourdoughs and their wild and woolly mining camps, the cowboys driving the first cattle onto the ranges of Montana, Pickett’s Charge, Sheridan’s Ride, the gunfight at the OK Corral, Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, the Wright Brothers, Alvin York, Lindbergh’s flight, the Dempsey-Tunney fights, the Dorsey Brothers, Wake Island, Colin Kelly, Audie Murphy, and a hundred other events and people that stir the American heart and reach deep into the American soul.

On the other hand, I suspect few Americans feel any particular affinity for Arabs, Asians, and Africans, let alone a kinfolk relationship, and even fewer Americans would want their children intermarrying with them. Those who claim they do, as political correctness demands, are lying to themselves—even as they flee their old and newly “diverse” neighborhoods for a far-flung white suburb. Most of all, though, Americans are under no moral or legal obligation to obliterate themselves. If suicide is a sin for individuals, should not suicide also be a sin for nations?

Leave a Reply