Transnationalism isn’t a term that is familiar to the American people. According to Peter Drucker, a leading advocate of transnationalism, a transnational company is one that operates in the global marketplace; that does its research wherever there are scientists and technicians, and manufactures where economics dictate (in many countries, that is); and that has a management that doesn’t feel any allegiance to the economic or national security interests of the country in which it is incorporated. It obtains its financing from institutions around the world. In short, it regards itself as a free agent in a global economy.

The transnational company represents a mutation of the multinational. American companies have had foreign subsidiaries for many decades, and the American multinational has been built around the national interest of the United States. But some such companies are moving from multinational to transnational, and in doing so are consciously discarding their basic American orientation.

A case in point is the NCR Corporation. On April 12, 1989, economics columnist Hobart Rowen of the Washington Post quoted Gilbert Williamson, president of NCR, as saying, “I was asked the other day about competitiveness. I replied that I don’t think about it at all. We at NCR think of ourselves as a globally competitive company that happens to be headquartered in the United States.”

Rowen went on to say with approval that “the modern corporation looks first to satisfying customers and to rolling up profits—forget the salute to the flag.” He noted that Williamson didn’t describe his company as American. “But five or six years ago, he almost certainly would have,” he said.

Peter Drucker wants mid-size as well as large American companies to go transnational—to divorce themselves from the US national interest. He urges smaller business units to take the same route, saying it is “easier for them to operate without much regard for national boundaries.” Mr. Drucker wants American business to begin thinking globally, though that may mean no longer thinking about what is good for the United States.

Writing in Business Month last June, Mr. Drucker said that “it does not matter to the transnational company which country is in the lead.” The focus is on successful financial transactions, irrespective of the interest of a particular country, its people, and institutions. For example, it wouldn’t matter that strategic trade with the Soviet Union may involve transfers of military technology that could endanger the United States, for a transnational company does not take such factors into account. Mr. Drucker says, “A company’s domicile has become a headquarters and communications center. It could be based anywhere.” And he argues that “[m]anagers need increasingly to base business policy on this new transnational superpower structure of business and industry.”

Indeed, Mr. Drucker goes on to insist that what really counts is international money flows. The rise or fall of the dollar isn’t, he argues, a matter of a business manager’s concern from the standpoint of the US national interest. “The ‘real’ economy of goods and services no longer dominates the transnational economy. The symbol economy of money and credit does.” He goes on to say that “ninety percent or more of the transnational economy’s financial transactions do not serve what economists would consider an economic function. They serve a purely financial function.”

Understand what that means: a transnational company would not be primarily concerned with manufactured products or services, but with financial transactions involving many countries, many banking institutions, and many currencies. Where, one wonders, is the public good in such a system, specifically the public good as envisioned by the American people and their government?

Mr. Drucker is not alone in favoring this new economic order. George Gilder, author of Wealth and Poverty, is another ardent advocate of the “no national borders” school of thought. He has argued that there is no more reason for a balance of trade between the US and Japan than between New York and Ohio. Ignoring the fact of national sovereignty, he favors the repeal of all security restrictions on strategic trade with the Soviet Union. For him borders have no meaning at all: he would open America’s gates to anyone who wants to move here. His anti-national one-worldism dovetails with the transnational concept.

Herbert Stein thinks along these same lines. He believes Americans should be free to acquire capital from the lowest-cost source, whether foreign or domestic. That the choice might create national dependency gives him no pause. He apparently is unconcerned that unsupervised flows could result in a loss of American control of American assets. In a letter to the Wall Street Journal he made the revealing statement that “I think this whole subject is confused by treating the flows of capital and goods as if there were flows between ‘countries.'”

But of course they are just that. Like it or not, Messrs. Drucker, Gilder, and Stein can’t deny the fact that the world is still organized on the basis of national states—national states with historical memories, historic and present-day political and military ambitions, cultural identities, and special national interests. Thus, while there are vast numbers of international economic transactions, there isn’t a true global economy, without barriers and state objectives.

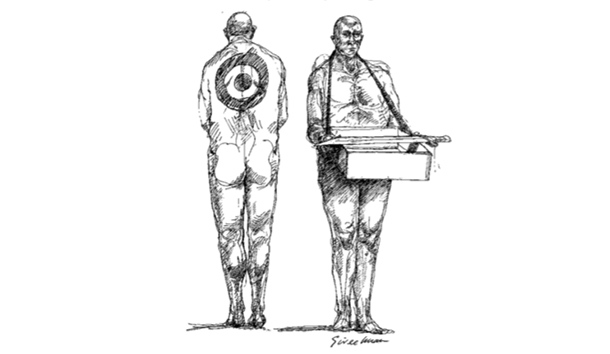

American companies don’t just “happen” to exist in America. Their American officers and managers are American citizens, with all the duties and responsibilities of citizenship. The companies themselves are incorporated under US law and are subject to it. As American companies they enjoy many benefits, including the protection that the United States government provides to American citizens and American commercial entities. At least part of these companies’ assets are held in American banking institutions that enjoy public safeguards. An American company is just that; it doesn’t exist in legal and constitutional limbo. Corporations aren’t stateless creatures; they, like citizens, can’t have it both ways. If a company doesn’t interid to be a part of the United States and help safeguard American economic interests, then it should incorporate somewhere else.

The problems that domestic American companies have experienced in recent years stem from two sources. The first is the penetration of the American market by foreign companies—often using transplant factories that displace American-owned, American-directed companies, as they come here with a host of home-based suppliers. The second is the hostile takeover craze and leveraged buyouts that have caused a mushrooming of corporate debt. A related problem is the use of so-called junk bonds in the LBOs, a financial practice designed for speculation rather than investment. A healthy free enterprise economy requires a very different kind of approach to the corporation.

Insofar as companies operating on the American scene are concerned, small, mid-size or big, law and public policy should be developed with the aim of minimizing regulation in a degree consistent with safety and financial regularity. But we cannot get away from the fact that the problem of foreign adversarial trade and the buying up of American assets also requires public understanding and legislative action. Call this protectionism, mercantilism, or what you like, but every country in the world is determined to maintain sovereign control over its assets and business structure. The great economic superpower of our time, Japan, protects its home market and closes its doors to a significant degree to imports, despite its lip service to free trade. Thus Japan awards all its public works contracts to Japanese firms—whereas in this country Japan is allowed to bid on and is awarded similar contracts, such as the building of a major new museum in Los Angeles.

It should be obvious that the United States can’t maintain its business and industrial system if this double standard continues to prevail. One step in the right direction by the Reagan administration was its creation of the Brady Commission, which called for more safeguards in the markets in order to prevent speculative abuses. (The commission’s recommendations were not implemented.) Passage last year of the Omnibus Trade Act was an important first move by the Congress. Also significant was President Bush’s decision, under the terms of this law, to cite Japan for unfair trading practices—a presidential action that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier.

What of large-scale overseas manufacturing by American companies for the purpose of selling their products in the American market? Here the government and public must recognize that the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution gives Congress the right to determine business rules in accord with the national interest. Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the Treasury, developed tariff plans that would ensure the development of the new republic’s infant industries. Only since World War II has that Hamiltonian view not prevailed, and that is because in 1945 the United States was the only country in the world with undarriaged industrial facilities.

Today things are different. Countries that forty years ago received vast US assistance to rebuild their economies have now become powerful competitors. Their factories are more modern and efficient, and as a general rule they have managed to keep their labor costs under control, while ours have soared. We have lost our lead in most major technologies, and are holding on to others by a thread. Our spending on scientific and technological research has declined. Foreign penetration of our universities and laboratories has become a problem, because foreign grants to these institutions have given other countries the benefits of American research. In Washington, massive foreign lobbying, involving hundreds of millions of dollars a year, continues to influence US government policy. (An example of this is the muting of government protests regarding the behavior of Japan’s Toshiba Corporation, which sold secret submarine technology to the Soviet Union. The cost of this will run in the billions of dollars, not to mention the strategic damage.)

As more products used by Americans and produced by American-owned companies are manufactured abroad, it isn’t surprising the idea has emerged that American-domiciled companies can and should be allowed to operate as though they didn’t have any responsibility to the labor needs of the American people. This desire to operate without any national limitations is clearly seen in the drive by companies in the US-USSR Trade and Economic Council to press for US-Soviet strategic trade in order to maximize short-term profits, all at the expense of the US national interest.

The underlying ideology of transnationalism has its appeal. For many of its proponents transnationalism is part of the grand design for remaking the world—a new version of the old one-worldism, envisioned now in a new supercorporate form.

To people who are less greedy or less idealistic than the transnationalists, the question of how Americans will be employed in the future is of great national concern. Runaway factories constitute a threat to our well-being. The thirteen hundred American-owned factories on the Mexican side of our Southern border represent severe losses to American communities where they would have been located—losses of jobs, payrolls, taxes, and opportunities for the future. So it is with American factories that have gone to Singapore, Taiwan, Brazil, and other countries where labor costs are low.

If transnational business is encouraged, the American people will suffer. Thousands of small and mid-size companies also will suffer, for they will lose their role as suppliers. At the same time, one can be sure that the cash holdings of the offshore plants will go into banks around the world, not into American-owned financial institutions. And the funds generated by these offshore entities, or at least a large part of them, will be available for investments in other countries—for job opportunities, research, and education in those countries—all to the disadvantage of the American people. Employment will decline, and serious public resentment and unrest may carry over into politics. American institutions, including universities and hospitals, will be deprived of funds now provided by American-based companies in hundreds of communities. In brief, the American economy will be hollowed out. The free enterprise system will rapidly lose support among the American people. It will lack the industrial base and technological resources—and the money—to maintain a strong national defense.

If the American-domiciled transnational company—distinct from the American company with foreign subsidiaries—is deemed to be contrary to the public interest, it can be required to adhere to the national interest by a number of means already established in law. For instance, restrictions on strategic trade have been in effect for many years. Reporting of fund transfers has been greatly expanded in recent years because of money laundering. Domestic Content laws may be imposed by Congress in order to limit foreign sourcing. The tax code offers innumerable possibilities by way of ensuring that funds earned abroad are repatriated and invested here. Laws can be enacted to require that all US operations abroad adhere to the same safety and environmental rules that govern plants in the United States.

If these measures prove inadequate, additional steps can be taken. H.P. Minsky, a professor of economics at Washington University, has pointed out that it is possible to revise corporate forms in American society, including a “move to some form of national incorporation law, perhaps only for giant corporations.” The terms of incorporation under such a law could include insistence on a national or conventional international business strategy and exclude the transnational approach that works against the national interest.

Such a law or package of laws would be comparable to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which transformed American business and prevented the participation of US companies in the domestic and international cartels then existing in the world. Like the Sherman Act, which President Theodore Roosevelt vigorously enforced, it would establish a new economic policy confirming national sovereignty in economic policy. The Sherman Act denied to monopolies and cartels the right to set economic policy for the nation. Its constitutionality has been confirmed time and again in the past century.

It should be recognized that such laws would only approximate what other democratic countries insist upon by way of ensuring that their nations’ overseas economic operations satisfy the needs of these countries. It’s unthinkable, for instance, that large Japanese companies operating abroad would oppose Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) guidance in operations that could be hurtful to the Japanese national interest. The British also have rules designed to safeguard the country’s strategic industries against foreign takeovers. As Peter Drucker points out, France, too, has strict rules on foreign investment that are political in character. Why should we be any different? The primacy of national politics—national interests—is certain to endure even as transnational companies strive to become sovereign economic units on their own.

In considering restrictions on the transnational trend, Americans also should consider developments in Europe. In 1992, the European Economic Community will become a much stronger economic unit. It’s clear that the Europeans are devising a power bloc with the intention of closing the region to economic invasion from other parts of the world. Many American-domiciled companies are hastening to get a foothold in the EEC countries before 1992, but it’s reasonable to conclude that the European countries will resist transnationalism from this side of the Atlantic—even as they promote transnationalism to the extent that it benefits themselves.

The alleged inevitability of transnationalism represents a kind of determinism that isn’t supported by history or the political facts of international life. There’s nothing inevitable about the development or implementation of an economic theory, whether Marxist or mercantilist. If American political leaders and businessmen in small, mid-size, and large national enterprises conclude that transnationalism is a threat to free enterprise rather than a fulfillment of it, if they opt for a strategic economic policy that focuses on America’s needs, then the transnationalism movement will die in the United States.

Such policies would not represent a break with our national tradition. They are grounded in the policy of the infant republic and the 19th century, under which the United States became the world’s largest industrial country, and they are strange or unusual only in the sense of the special circumstances that prevailed after World War II, which became the basis of a doctrinal obsession (in some quarters) with free trade. Today the national circumstances have changed and are likely to change even more as we move into the 21st century. The US already has begun to respond, especially to the emergence of Japan as an economic superpower and adversary, closely followed by other Pacific Rim countries. The nationalism inherent in this proposed economic policy is appropriate to an era in which nationalism is more pronounced than at any time in 45 years, and in which internationalism is widely supported as a theory rather than a practice. If transnationalism represents a positive good to the American people, this has not yet been demonstrated. The arguments advanced for it by Mr. Drucker and others only justify it in terms of what it may do for a limited number of corporate entities and their shareholders.

Some businesses are already waking up. The International Business Machines Corporation is reported to be changing its corporate strategy to focus on its role as an American company. The Washington Post reported last June that IBM, with 40 percent of its employees overseas, is accentuating its role in the United States. It helped launch an American consortium of companies to make computer memory chips in and for the United States. Vice Chairman J.D. Kujehler told a Senate committee that IBM is “a US-based company.” The Post described the consortium as “the latest example of the emerging high-tech nationalism.” It appears, therefore, that IBM is rethinking its global strategy to accommodate American concerns. American-based entities, which receive the protection of the US government, have to serve the American national interest. We cannot allow them to do otherwise.

Leave a Reply