Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once referred to the Cheka as “the only punitive organ in human history that combined in one set of hands investigation, arrest, interrogation, prosecution, trial, and execution of the verdict.” He was probably mistaken about “human history,” but his anger was just. What he chronicled was indefinite imprisonment without trial; investigations and indictments politically motivated, initiated, and controlled; arbitrary evidence gathering; trial by media and assumption of guilt.

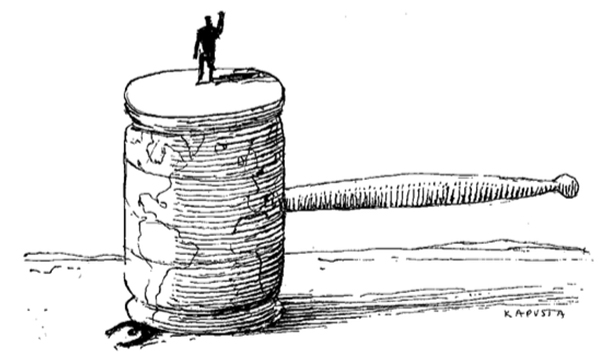

Precisely these techniques, honed by the totalitarian scum of our century, have become the hallmark of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTFY), based in The Hague. After the decline of higher cynicism in the name of human progress, we now witness the ascent of higher cynicism in the name of human rights. It is the New World Order’s posthumous tribute to Felix Dzerzhinsky.

ICTFY was established by the Security Council of the United Nations in 1993 on the basis of Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter (Resolution 827), with the “jurisdiction” for crimes committed after January 1, 1991. Why only “the former Yugoslavia,” and why only the past five years? The strict answer is that the United States did not want to put its generals on trial for killing Vietnamese civilians, and did not want the embarrassment of charging the Croat mass murderers who have been untouched since 1945.

But the U.S. Ambassador at the United Nations, Madeleine Albright, supplies a more attractive, less honest answer. Speaking at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum on April 12, 1994, she declared that “there is no more appropriate a place to discuss the War Crimes Tribunal for former Yugoslavia.” In other words, the enormity of recent crimes in the Balkans supposedly sets them apart from all other wretched spots on our planet, and makes them comparable only to the Ultimate Horror of Auschwitz, Babi Yar, and Belsen.

According to Rudolph J. Rummel in the Journal of Peace Research (1994), in the five decades since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, there have been well over one hundred million fatalities due to war, genocide, democide, politicide, and mass murder. Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge killed two million of their compatriots—one third of Cambodia’s population—in only four years (1975-78). This was but an offshoot of Mao’s less known, more grandiose attempt at social engineering after 1949, which physically destroyed some 35 million men, women, and children. The Indonesian Army and its affiliates killed half a million people in 1965-66. The precise number of victims of India’s partition is unknown, but exceeds one million. This figure was easily exceeded by Pakistan’s brief and savage democide in today’s Bangladesh in 1971. Dictatorships in Afghanistan, Angola, Albania, Rumania, Ethiopia, Iraq, North Korea, and Uganda have contributed their own hecatombs to the total. Even that old darling of Western liberals. Marshal Tito, after being brought to Belgrade by the Red Army in October 1944, dispatched hundreds of thousands of Yugoslav citizens; the victims were not only the Volksdeutsche of Vojvodina who did not survive deportations in 1945-47, but any real, potential, or imagined enemies of the regime.

While democracies murder relatively few of their own citizens (which is scant comfort to a child burned at Waco, or to Randy Weaver), they are less restrained in killing foreign civilians in declared or undeclared wars. Dresden and Hiroshima set the scene for indiscriminate bombings of Vietnamese and Iraqi cities. We know that the general strategic bombing policy of the Allies in 1942-45 was to terrorize urban centers. However, it may be years before we are told of the estimate for civilian deaths, in Hanoi in 1972, in Baghdad in 1991, or in the Bosnian Serb Republic in 1995; and there will be no trials of the culprits.

Compared to the horrors of Afro-Asian postcolonial killing fields, the war in the Balkans can be seen for what it is: a medium- sized local conflict. Before any facile comparisons of Yugoslavia to the Holocaust are accepted at face value, it is legitimate to ask how many have actually died. For President Clinton, addressing the nation on November 27, 1995, the easy answer was 250,000—and that in Bosnia alone. For his Defense Secretary, William Perry, two sets of figures seem to be equally valid. Testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 7, 1995, he said that in 1992 “there were, by our best estimate, about 130,000 civilian casualties In 1993, that number was reduced to about 12,000, and last year, 1994, the estimate was about 2,500.” But four months later, on October 18, he told the House International Relations Committee that “the war in Bosnia has been going on for more than three-and-a-half years, with more than 200,000 people killed.”

Was that latter figure based on anything but repetition? Counting bodies may be poor form (“even one death is one too many”), but it has to be done if we are not to abet the further exploitation of lies and distortions for political purposes. According to the only serious study published on the subject so far, by George Kenney (“All Told, How Many People Have Died in Bosnia,” New York Times Magazine, April 23, 1995), former acting chief of the Yugoslav desk at the State Department, “Bosnia isn’t the Holocaust or Rwanda; it’s Lebanon.” Kenney insists that the number of fatalities in Bosnia’s war is between 25,000 and 60,000 on all sides.

The “Bosnian Holocaust” story was fabricated by the Muslim side as part of a wide-ranging and effective PR campaign. In December 1992, the Izetbegovic authorities first claimed that there were 128,444 dead on the “Bosnian” side (including Croats and “Serbs loyal to the Bosnian government”). According to Kenney, this figure was cooked by adding together the 17,466 confirmed dead until that time, ‘and the 111,000 that the Muslims had already claimed as missing. He stresses that, at first, such high numbers were not accepted:

But on June 28, 1993—as near as I can pin it down—the Bosnian Deputy Minister of Information, Senada Kreso, told journalists that 200,000 had died. Knowing her from her service as my translator and guide around Sarajevo, I believe that this was an outburst of naive zeal. Nevertheless, the major newspapers and wire services quickly began using these numbers, unsourced and unsupported. . . . An inert press simply never bothered to learn the origins of the numbers it reported.

Ever since, Bosnian-Muslim propagandists have peddled the story of the “Bosnian Holocaust” without being seriously challenged. In fact, after an initial bout of heavy fighting, from 1993 to mid-1995, there was a period of relative calm on most fronts in Bosnia, interrupted by brief outbursts in isolated localities (Gorazde, Bihac). Stories of mass murder and atrocities are yet to be substantiated with anything better than aerial photos of freshly plowed fields. The Red Cross has been able to confirm under 20,000 deaths on all sides. Analysts at the CIA and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research put fatalities in the tens of thousands. This is close to the view of British military intelligence experts: a year ago they estimated fatalities to be 50,000 to 60,000. Even if the as yet unknown number of Serbs killed by NATO air power and the combined Croat-Muslim offensive last September are included, the war in Bosnia is unlikely to have resulted in more than 70,000 deaths. Including Croatia/Krajina, the Yugoslav wars of 1991-95 have killed up to, but not more than, 100,000 people.

So why the war crimes Tribunal? Mrs. Albright’s answer is that “the U.S. Government does not believe that because some war crimes may go unpunished, all must.” Needless to say, any determination of which ones should be punished—if left to the United States government—becomes not a legal, but a political decision. Susan Woodward of the Brookings Institution says that the Tribunal was pushed largely by the United States for political reasons: “The accusations became a servant of American policy toward the conflict itself, which required a conspiracy of silence about parties which were not considered aggressors.” The Muslims and Croats could thus get away with murder, literally and figuratively. The Serbs were to be pilloried, and the “Tribunal” was needed to give due legitimacy—and legality—to that decision.

The U.N. Genocide Convention could not, in any case, provide the basis for the Tribunal. It is an international treaty, approved by the General Assembly and ratified by member-states, which does not endow the U.N. with radical new powers. In fact, the Security Council acted illegally in setting up the Tribunal: it had no authority to do so. (Boutros-Ghali himself declared that “in asking the Secretary-General to consider this project, the Security Council has given itself an entirely new mandate.”)

The formal basis invoked for the Tribunal, Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter, deals with “threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression,” and to meet them it authorizes the U.N. to deploy the armed forces of its member-states in peacekeeping operations. It would take a very flexible legal mind indeed to interpret this as carte blanche to investigate people, indict them, try them, find them guilty, and keep them in prison.

Invocation of Article 29 in the resolution establishing the Tribunal gives the game away: the Security Council may establish such subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for the performance of its functions. This amounts to an admission that the Tribunal is not an independent court of law but a “subsidiary organ” of its political masters. But while the Tribunal remains fundamentally subordinate to the Security Council, its statute provides it with primacy over national courts, including the authority to demand the surrender of the accused. This is in clear violation of the U.N. Charter, which insists that the U.N. may not usurp the sovereign rights of states.

A dangerous precedent has been created, and it would be shortsighted for the American public to overlook it. ICTFY may yet prove to be a step toward the globalist dream of a permanent International Criminal Tribunal. But the sponsors of ICTFY—shortsightedly, perhaps—do not envisage “international peace-keepers” patrolling America’s racially or ethnically troubled areas; they do not contemplate Somalese or Saudi judges, sitting on such a Tribunal, demanding extradition of Americans accused of “hate crimes” against, say, the Nation of Islam.

The Albrights of this world have a different scenario in mind. They do not seek to delegitimize war crimes per se, but to enhance their power to decide what is a war crime on the basis of current political calculations. Applied in practice, it means that when Bosnian Muslims are shelled, driven from their homes, or murdered, they are seething with indignation. When Serbs are driven from their homes in the Krajina or in Sarajevo in the hundreds of thousands, or are discovered with their throats cut, they pretend not to see. When Serbs take Srebrenica, it is “genocide.” When Serbs are cleansed from Knin, Drvar, Grahovo or Petrovac, there is but silence, or an exultant cry that they had it coming.

To the Albrightesque mind there is no danger of the U.S. having to accept the jurisdiction of an International Criminal Tribunal created by the resolution of the U.N. Security Council, without congressional consent, without presidential signature, with primacy over the Constitution and over American courts. Such indignities are reserved for a Serbia, or a Rwanda. The intent is not to submit, but to control; the goal is not a new global superstate but a front for deja-vu politics. As C. Douglas Lummis wrote in the Nation (“Time to Watch the Watchers,” September 26,1994):

We can be confident that only the borders of middling and small countries will show a “new legal permeability.” These are the same countries whose borders were always “permeable” throughout the age of colonialism and European colonial imperialism: the countries of the Third World and Eastern Europe. . . . As inspiration for a grassroots movement, human rights is a vital and precious weapon against the state, the corporation and other organized power. When it raises armies and jailers, however, the time has come to start watching the watchers.

The populist, universalist rhetoric used by the American foreign policy establishment to justify The Hague Tribunal, has been deployed ad nauseam to misrepresent “Bosnia” in general. Similar rhetoric may be found in Europe’s leftist-leaning press (The Guardian, Le Monde) and among a small core of professional “intellectuals” (the most contemptible of whom are France’s trio of laptop-bombardiers; Henri-Levy, Fienkelkraut, and Glucksman). But among the political class of Paris, London, or Rome, Clinton’s and Albright’s approach is basically a heresy, a deviation from the European norm, as it has been ever since a misreading of Montesquieu and the revolutionary ardor of a Tom Paine divided America’s culture from its European roots.

Lofty rhetoric apart, America’s policy in the Balkans has never been about the Balkans. President Wilson, while advocating the creation of Yugoslavia, did not know, or care, that the unification of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in 1918 was at least a half-century overdue: had it happened at the time of Bismarck’s and Mazzini’s unification projects, it could have worked. By the time of Versailles the process of separate cultural development and creation of separate national identities among the South Slavs had been completed.

With similar historical inattention, America’s present leaders are deliberately ignoring the traumatic legacy of the massacre which Croat and Bosnian Muslim quislings systematically perpetrated against Serbs, Jews, and Gypsies in 1941-45. What has happened in Croatia and Bosnia in 1991-95 cannot be understood without taking account of the Ustase “policy of racial purification that went even beyond Nazi practices” (Encyclopedia Britannica). The murder of hundreds of thousands of Serbs during Pavelic’s reign of terror is a contemporary political fact of life, just as the Holocaust is for the Jews.

But what happened in Washington? There are no intrinsic reasons for the anti-Serb policy of the administration. The Serbs had lived in one state since 1918, when “Yugoslavia” came into being. When the breakaway republics tried in 1991- 92 to force over two million of them to become minorities, literally overnight, they reacted, and often overreacted. The issue was not that of aggression versus collective security; instead, the principle of territorial integrity of the former republics (Croatia, Bosnia) fatally clashed with the principle of self-determination of the people (the Serbs). There could have been no objection to the striving of Croats and Bosnian Muslims to create their own states. But equally there could have been no justification for forcing over two million Serbs west of the Drina River to be incorporated into those states.

This begs the fundamental question of the Bosnian war: If the collapse of Yugoslavia was due to the allegedly insurmountable contradictions between its ethnic groups, is not Bosnia even less a viable state? Are not the divergent interests among its ethnic groups even more strongly pronounced? The American advocates of a “multiethnic” Bosnia have never satisfactorily explained the paradox that their pleas are also the arguments for the reintegration of Yugoslavia, while their objections to such reintegration are also the arguments against Bosnia’s viability.

What, then, is the motive for the United States to disregard all such questions—reasonable in themselves—and to insist on forcing the Serbs to submit to the rule of their enemies, or accept mass exodus, such as the cleansing of the Krajina last August, or Sarajevo today?

The motives of this anti-Serb stance in Washington are not rooted in the concern for the Muslims of Bosnia as such, or indeed any higher moral principle. United States policy has no basis in the law of nations, or in the notions of truth or justice. It is the end-result of the interaction of pressure groups within the American power structure. United States foreign policy in general, and “Bosnian” policy in particular, reflects those groups’ concern for their particular interest and global policy objectives.

A Washington insider put it bluntly in the early days of the conflict:

The simple facts are these: we are getting incredible pressure from the Saudis and others to help the Muslim cause in Bosnia. They remind us that the Islamic world provides us with all the oil we want at relatively low prices, that Islamic states have billions of petrodollars to invest in “friendly states” and offer a potential market of over one billion people for the goods and services of “friendly countries”; and finally, that the peace process between Israel and the Islamic world would go better if Israel’s main friend was also a friend to Islamic countries. When you weigh these facts against what eight million Serbs can do for America’s interests, it’s clear what direction our policy is going to take.

There are two key strategic goals of American foreign policy today. One is that the United States retain its role as the perceived leader of the “international community.” The other is that America remain the foremost economic power in the world. Thus the war in the Balkans evolved from a Yugoslav disaster and a European inconvenience into a major test of “U.S. leadership.” This was made possible by a bogus consensus which passed for Europe’s Balkan policy. This consensus, amplified in the media, limited the scope for meaningful debate. “Europe” was thus unable to resist the new thrust of Bosnian policy coming from Washington.

While Europe resorted to the lowest common denominator in lieu of coherent policy, a violently anti-Serb, agenda-driven form of Realpolitik dominated America’s Bosnian policy. Instead of the neo-Wilsonian “moralist” approach—however misguided—egotistic unilateralism had grown rampant in Washington. Globalist phraseology should not mislead us. The intent is no longer to achieve a consensus; it is to force others to acquiesce to the American position. Just as Germany sought to paint its Maastricht Diktat on Croatia’s recognition in December 1991 as an expression of the “European consensus,” after 1993 Washington’s faits accomplis—The Hague Tribunal included—were straightfacedly labeled by the administration “the will of the international community.”

Just as the EU has lived with the consequences of its acquiescence to Herr Genscher’s fist-banging in Maastricht, NATO has felt the brunt of the new American agenda in foreign policy. Most NATO partners were resentful but helpless when the United States resorted to covert action—with the support of Turkey and Germany—to smuggle arms into Croatia and Bosnia in violation of U.N. resolutions. America’s refusal to support pre-1994 attempts to end the war (the EU Lisbon formula in 1992, the Vance-Owen and Owen-Stoltenberg plans in 1993), and its unilateral actions to directly aid the Muslim and Croat cause have frustrated the Europeans, but they were helpless.

The rest is history. Predictably, catching “war criminals” in Bosnia has now become another American obsession, a mediated crusade that may yet make a durable peace impossible. The American-led operation was initially presented as a limited effort to implement the Dayton peace accord by creating a “zone of separation” between the factions and enforcing a cease-fire. But a full-fledged political campaign is under way in Washington to turn IFOR into an international gendarmerie, obliged to assist the Hague Tribunal in apprehending accused war criminals.

At the root of the problem is a deeply flawed model of the new Balkan order, designed in Washington and Bonn, which seeks to satisfy the aspirations of virtually all ethnic groups in former Yugoslavia—except those “eight million Serbs.” This is a disastrous strategy for all concerned. Even if forced into submission now, the Serb nation shall have no stake in the ensuing order of things. This will cause imbalance and strife for years, or decades. It will entangle the United States in a Balkan quagmire, and guarantee a new war as soon as Clinton’s and Albright’s successors lose interest in underwriting the ill-gotten gains of America’s new Balkan clients.

The little-known details of the way The Hague Tribunal operates go beyond the issues of legality and politics; they constitute a moral debacle of the highest order. Here are some of the facts. First, in October 1992, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 780, establishing a five-member commission of experts to investigate war crimes and other violations of international law in the former Yugoslavia. DePaul University law professor Mammoud Cherif Bassiouni was chosen to serve on the commission and to serve as its “rapporteur,” to gather and analyze the evidence of war crimes. Bassiouni subsequently became the chairman of the commission, and its work provided the initial impetus to the advocates of The Hague Tribunal. The “War Crimes Project” at DePaul was the first data base to the Tribunal’s prosecutor.

Professor Bassiouni is a devout Muslim. He has never sought to conceal his core values and prejudices in his books and articles, which include the following: The Palestinians’ Right of Self-Determination, Introduction to Islam, The Islamic Criminal Justice System, Jewish-Arab Relations, Criminal Procedure (Islamic Law), and The Palestinian Intifada: A Record of Israeli Repression.

Obviously, entrusting Professor Bassiouni with collecting evidence in a conflict between Muslims and non-Muslims was tantamount to putting Count Dracula in charge of a blood bank. It was a gesture of contempt for the Serbs and appeasement of oil-rich friends. As expected, he had consistently refused to accept evidence of Croat and Muslim crimes against the Serbs, while his staff have not hesitated to include thirdhand hearsay and anonymous submissions from Muslim and Croat sources.

Bassiouni initiated and legitimized a selective approach to evidence gathering which has become habitual at The Hague, and which prompted David Binder of the New York Times to declare the entire War Crimes Tribunal unfair:

Independent Serbian efforts to collect war crimes data and not only data involving Serbs, but other nationalities has been ignored. A large volume of data has been simply brushed aside. . . . I think it is a farce frankly, and it’s made more of a farce by their naming political leaders as potential war criminals. . . . If you’re going to start listing potential war criminals, you might add [German] Chancellor Kohl and, then Foreign Minister, Hans Dietrich Genscher, to the list of potential war criminals for what they did in pushing the recognition of Slovenia and Croatia, and thereby, spreading and deepening the conflict in the Balkans.

Bassiouni’s “Final Report” unambiguously blamed the Serbs for aggression, premeditated ethnic cleansing, mass rapes, and all the rest. It was widely circulated in five languages under the U.N. cover. The outside world perceived it as an official U.N. document based on facts. It was an exercise in disinformation worthy of Goebbels. Few copies of the 3,000 page Annex were circulated, with primary evidence on which the findings were based. This Annex simply listed thousands of anti-Serb submissions, without attempting to evaluate their veracity. Bassiouni’s magnum opus would have been laughed out of any real court, in the United States or anywhere else in the Western world—just as he himself would have been disqualified from serving on an American jury in any dispute involving a Muslim and a non-Muslim.

Second, he who pays the piper calls the tune. As Brecht put it, “You want justice, but do you want to pay for it, hm? When you go to a butcher you know you have to pay, but you people go to a judge as if you were off to a funeral supper.”

In the first months of its existence. The Hague Tribunal received 93.4 percent of its funding from two Islamic countries, Pakistan and Malaysia. Mirabile dictu: both have been given the right to appoint judges to the panel. Both countries have also been among the staunchest supporters of the Muslim side in Bosnia ever since the beginning of the war, supplying it with weapons in violation of U.N. resolutions. The British journalist Nora Beloff points out that such composition of The Hague Tribunal precludes it from meeting Western standards for an independent judiciary:

It was formed on the model for the Nuremberg Tribunal, with the Serbs cast in advance for the role played at Nuremberg by the Nazis. . . . Selected governments, representing different race and religions, were free to name their own judges. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, knowing that the Americans were primarily interested in incriminating the Serbs (and so commanding the “moral high ground”), was careful to exclude countries representing the Orthodox Christian tradition. These might have been sympathetic to the Serbs. Most of the judges came from countries where it is normal to decide the verdict in advance of the trial.

The panel also includes a Nigerian (where they execute poets for their writings), a Chinese (where nobody has been prosecuted for Tiananmen, let alone the horrors of the Mao era), and an Egyptian Muslim. With guardians like these, the New World justice needs no transgressors.

Third, the Bosnian Muslim government has stage-managed three well-publicized explosions in Sarajevo, in May 1992, February 1994, and August 1995. A total of 121 civilians were killed by these blasts. The first incident (the “breadqueue massacre”) facilitated the imposition of punitive sanctions against Serbia and Montenegro. The second—the infamous Markale Market incident—^led to the imposition of a heavy weapons exclusion zone around Sarajevo. The third provided the pretext for massive air raids against the Bosnian Serb Republic.

While each of these incidents was blamed on the Serbs, Western intelligence analysts and ballistic experts know the truth. So do U.N. investigators, but their findings have been kept secret on American insistence. The facts of each case have been extensively reported in Europe and Canada (The Independent, The Toronto Star, The Times) and in some American periodicals (the Nation and Chronicles). They have not been reported by major American networks, wire agencies, or daily newspapers. It would be highly embarrassing to the administration if they were, since each of those incidents provides ample grounds to take Izetbegovic & Co. on the first plane to The Hague. It is also striking that Dr. Karadzic and General Mladic have been accused of all manner of nastiness, but the inquisitors at The Hague have shirked from attributing even one of these highly publicized massacres to the Bosnian Serb leadership.

Fourth, the indictments of the Tribunal are uninhibitedly selective. A total of 46 Serbs have been accused of war crimes against Croats and Muslims, and seven Croats are indicted for crimes against Muslims. In the meantime, the Serbs have come to constitute the largest refugee population outside sub-Saharan Africa, and there are thousands of well-documented cases of atrocities against Serb civilians by Croat and Muslim military and civilian authorities.

The Tribunal’s bias has been exposed in the indictment against Milan Martic, leader of the Krajina Serbs, for having ordered the bombing of Zagreb—which cost five lives. In their attacks against Western Slavonia in May and the Krajina in August 1995, Tudjman’s troops had ethnically cleansed 250,000 Serbs and killed between J2,000 and 15,000 Serb civilians. Asked to explain the discrepancy between what happened in the Krajina and the indictment against Martic alone, Minna Schrag, formerly of the ICTY prosecutor’s office, admitted that the decision was political:

We at the ICTY Office of the Prosecutor recognized that the ICTY could not prosecute every violation of international law that occurred in the former Yugoslavia. . . . As for why some things are prosecuted and others are not, that is a question that I think arises in every prosecutor’s office. It involves decisions about how to allocate scarce resources, priorities, purpose. And on a larger scale, why the international community decided to set up an ad hoc Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, but not for several other places where there appear to have been serious violations of international law, is also, I suppose, explained by practical politics and many other factors.

The model for The Hague Tribunal is not Nuremberg 1946, but Moscow 1938. It is a deeply flawed institution, created for dishonest political ends. It is also a travesty of justice, as understood and practiced in the civilized world. Ted Galen Carpenter lucidly summarized the gut feeling of many Americans in a recent column:

The Yugoslav war crimes trials have begun amid declarations of the international community’s determination to bring perpetrators of atrocities to justice. Unfortunately, the proceedings themselves are an atrocity. . . . The Tribunal, like the Western governments that pressed for its creation, is blind to the reality that there are Serb victims in the Yugoslav war. The world does not need another example of moral posturing and double standards masquerading as a search for justice. It would be an act of mercy to end this farce as soon as possible.

The farce of Bosnian Serb General Djukic’s arrest by the Muslims last February, his transfer to The Hague by IFOR, and his indictment by the Tribunal only after his refusal to testify against Mladic and Karadzic, is worthy of the judicial proceedings in a Banana Republic. Such seedy episodes should not be allowed to continue under the honorable Roman name of a “Tribunal.” They are consistent only with the brave new world in which the United Nations is generating criminal law in chilly disregard of the dictum that people can be obligated to obey only those laws to which they have consented.

The Hague sends a clear message to the Serbs, that in today’s world there can be crime without punishment, and punishment without crime, depending on the arbitrary will of “the international community” embodied in Messrs. Clinton, Perry, Albright, and Christopher. To the rest of the world the message is equally clear: keep quiet, toe the line, eat your McDonald’s, listen to your Madonna, watch your Terminator, forget your history and culture and that Eurocentric trash about dignity and the hierarchy of values . . . and you’ll be all right. For those who refuse to play along, there will be other “Tribunals” globally, and Prozessen locally. The bell, it does not toll just for the Serbs, it tolls for thee . . .

Leave a Reply