Popular culture in the West, and especially in North America, is an illusion, mostly electronic, that does not feed the soul. Indeed, it claims to do nothing but feed the senses, and as such it tends toward universal barbarism, fostering ignorance and encouraging violence.

Beneath the illusion there is, however, one great civilization, and it is the civilization built upon the Hebrew Scriptures and the best of Greek philosophy, as these were incorporated into a living religion based on the regenerating power of life in Jesus Christ. If its claim that God became Man is true, it is the fulfillment of human destiny and human history. It is the only thing that matters.

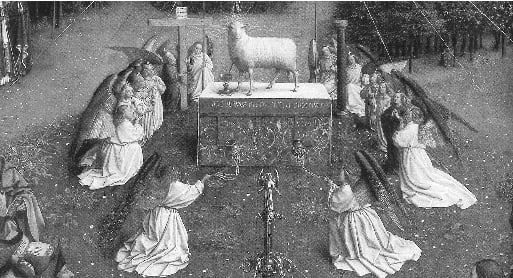

In the beginning this civilization did not raise monuments to itself, no great basilicas, no Dante, no Adoration of the Lamb, but it was nevertheless in place around the Mediterranean within the historical span defined by the New Testament, between a.d. 50 and 80. In the most fundamental sense, this one civilization, in contrast to the great civilization of the East, rested and rests upon two presuppositions: that being is good—that, in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ words, there is a “freshness deep down things” that cannot be overborne by the smut of human failure and folly—and that something, something individual that is itself and not some other thing, truly exists. If these seem obvious it is because they have been successfully defended by a great intellectual tradition.

My purpose is to remind us of the characteristics of the only civilization that matters, characteristics which make it supremely valuable. But first, three brief historical caveats.

We should not expect that Christianity will ever present itself as a peaceable kingdom which claims the unqualified assent of all of its subjects. Historically, it has always existed at the heart of an intellectual and moral storm, beginning in the 50’s with Saint Paul’s converts at Corinth who, while considering themselves Christians in good standing, denied the resurrection, the central Christian dogma. From the very beginning to the present, the Church has always been involved in a battle for survival, which She has always won and always will, and that despite the intermittent follies and fecklessness of those who are supposed to represent and defend Her.

Persons—and, hence, civilizations—are not defined exclusively or even decisively by their moral achievements but by the axes along which their inherent moral pressures move. Christianity can provide in the lives of the saints examples of unambiguous fruition and resolution, leading decisively to the presence of God, peace, joy, and fulfillment. But as far as culture goes, all that Christianity can do is encourage the best, moderate passions, and propose a view of human nature and destiny that makes sense of the world as it is experienced. Yet this is no small thing. The claim of Christian civilization is not that it makes angels but that it may make better men.

Christian civilization is not Chartres, Amiens, and Shakespeare. It is not even the Code of Justinian and the printed Bible. It is persons in community who do certain things because they think in certain ways and are inspired in certain ways. Thus, the vast detritus of European cultural artifacts is a witness but not a living reality, especially now, when the artifacts of the noble past exist in weakened context or none at all. It is easy to think that the makers of Chartres and Amiens were stonecutters and sculptors. But the ultimate maker was Christ, and the stone and glass gain their significance as an act of praise to Him.

The civilization Christ made is still alive and very well, and if it is not a majority culture in the European West, a proposition which I consider debatable—something that has to be put to death so persistently and proclaimed obsolete annually is hardly dead—it is still the only culture worth knowing or worth living in. Furthermore, it has often flourished best when opposition has made its members clarify their loyalties; prosperity and cultural dominance have never been unmixed blessings. The Founder never promised a conclusive historical triumph or indeed an historical triumph of any kind. He asked, instead, “When I return, will I find any faith?” Since the Constantinian century, when Eusebius could write of the emperor as savior of the world, the Church has been bedeviled by a longing for the reassurance provided by political affirmation. Whether the expression of Christian faith achieved in such hostile environments as a Marxist gulag, sub-Saharan Africa, or Manhattan in the 1970’s had greater success than the apparent triumphs of the age of Augustine or Aquinas is at least an open question.

Christianity is a civilization like no other because it rests on the foundation of what Newman would call a fact, that fact being the power of Pentecost, purchased by the sacrifice and resurrection of Jesus Christ, to renew and perfect human nature. It is a life lived objectively in the light of the condescending love of God and fed by the sacraments that join the believer to the Lord, notably the Eucharist, the celebration of which is perhaps still the single act shared most widely by citizens of the world Christ made.

Since the Founder was both a divine-human Person and Reason Himself, the civilization Christ inspired could never inhabit the precincts of unreason. With Justin Martyr’s claim, made at the dawn of the Christian world, that whatever is true belongs to Christians, the degeneration of the Faith Christ and His apostles taught into a cult or an enthusiasm was forever precluded.

Christianity created a literature whose compelling truth and vivifying images found out the meaning of the old philosophers and led imagination into the terrain occupied by Dante and Shakespeare. Co-opting the great Greeks and cherishing Vergil, that literature has provided questions of eternal significance that mark out a way and a mirror for life that delights as it illustrates.

The soil in which the new civilization was planted was humility, which was only obliquely and incidentally a pagan virtue. “The rulers of the gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you. On the contrary, whoever wishes to be great among you shall be your servant” (Matthew 20:25). In the Gospel of John, the narrative of the Last Supper is displaced by the account of Jesus washing His disciples’ feet: “You call me Master and Lord, and you say well for so I am. If, therefore I, the Lord and Master, have washed your feet, you ought also to wash the feet of one another. For I have given you an example, that as I have done, so you should do.” Power is universally addictive, but in a civilization in which princes wash the feet of beggars on Maundy Thursday and in which a girl who says to God “Be it unto me according to thy word” is loudly proclaimed to be the Mother of God, some other principle haunts the precincts of human pride.

While this new world incorporated the natural virtues of Aristotle and Cicero, its citizens lived with the empowering reality of faith, hope, and charity, gifts given by the Holy Spirit in baptism. Faith, hope, and love made a new world. The legal charter of the new order of the ages was Matthew 5:17, in which the law was made a thing of the heart; its empowering reality was Pentecost. Cicero and Marcus Aurelius gave good advice; Jesus and Saint Paul offered a new life.

Christian civilization reconfigured and continues to moderate the disastrous consequences sin had wrought for the relations between men and women, proposing restraint, purity of heart, and imagining marriage as analogous to the relation between Christ and Church. Incidental to this was the formalization of the purpose of marriage (and, hence, of sex) as the procreation of children and their nurture. (One of the specific moral contributions of Judaism which Christianity co-opted was the rejection of homosexuality, which had been variously tolerated or celebrated by the Greeks and Romans.) Along the way childhood was rescued from the dangers in which it always existed in the pre-Christian world. One could not and cannot be callous about babies when the image that complements the Man on the Cross is a woman holding a Child—that Child, the Son of God.

The one civilization teaches regard for the unprotected, the weakest, and the least of these and holds in contempt brutality and hardness of heart. It does not disregard the poor and pander to the rich because they are rich. Wealth is not indicative of moral worth, and may indeed divert the soul from God, and the poor may be directed toward Christ by their neediness. The incompetent, the sick, the disabled are seen as bearing the results of Original Sin for us all and therefore as deserving of the unqualified protection of all.

This is a civilization that teaches gentleness and patience, not rudeness and anger. Saint Paul lists among the effects of the divine charity in human life such virtues as patience and kindness. What it does not promote is envy, pretension, haughtiness, ambition, self-seeking, and irascibility. It rejoices not in evil but in the truth; bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. The possibility of charity is the ground of the gentle civilization of the Middle Ages and of its present heirs. Courtesy is the child of charity.

This civilization is built not around fear but around hope. Life is all future; this world is a sign of the world that is coming. Every good that exists here points toward the perfection that will be. And death has lost its sting so that life can be an adventure. The Parable of the Talents is about courage and adventure: The third man will not adventure and is therefore cast into outer darkness. If there is a second great civilization it is generically Oriental and is characterized by the drive toward stasis, toward keeping things in place. Christianity is loaded toward adventure, which is why it rejects, among other illusory systems, socialism.

Christianity assumes that, beneath and beyond the flaw called Original Sin, life is good, very good. The body is not a prison; history is not an illusion; the soul is not divine. Being is good, said Aristotle; real things must have a real fruition, said Saint Irenaeus, not passing away into nothing but growing toward perfection. Although always threatened by the shadows of evil, the world that has the Eucharist at its center is not chiefly a minefield to be navigated on the way to safe harbor but a sacrament of the New Creation in which the contrapuntal rhythms of sin and disorder are always bathed in God’s beckoning love.

Christianity frees mankind from the tyranny of the secular because it frees man from the fear that, in every secular regime, replaces confidence in God’s providence with anxiety for tomorrow. It is not easy to find a modern or postmodern regime in which a carefully, if not always consciously, cultivated pusillanimity does not serve as the context for a soft tyranny that promises protection from the pain of life. This is a promise such regimes cannot redeem, or can redeem only in the bogus currency of a fragile secular security that must deny the nobility of the human spirit. Beyond the cross is the resurrection to life. Beyond the government guarantee, nothing. The tendency of the regime, from Augustus to the statists of postmodernity, is to make an ultimate claim to the loyalty of the citizen in the name of self-interest. In the civilization formed by love and self-denial, this claim rings hollow.

How this one great civilization is received by persons is a matter into which social history cannot fruitfully inquire. There are common missteps and misunderstandings that always lurk in the shadows. Having Christianity without Christ will not work. The attempt to alienate the virtues from their transcendent ground, cutting the root while retaining certain effects, will result in a religious atheism that tends to tyranny. Suppressing Christianity into a private religion disengaged from the life of the city is impossible, not because Christianity can triumph culturally but because its witness cannot be kept indoors.

There is, of course, a war on, but it is not the culture war so loudly championed. It is not a war with the ACLU or the academic establishment or the proponents of tyranny, although it is right to contend with such. It is the same war referenced by Saint Paul when he wrote that we contend not with flesh and blood but with spiritual wickedness in high places. The ultimate defeat of these dark powers is assured. The decisive battle was won when God became Man: The kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our God and of His Christ. The sign that the Prophet of Patmos was right is the continuing rage of the Ancient Enemy. He has made an alternative story of creation. Within the halls of great universities he has redefined man as a clever, sex-seeking animal. He has raised up a mighty salvation in worldliness. His prophets Dawkins and Hitchens, like Jeremiahs wandering the streets of Jerusalem, driven by the necessity to undeceive, proclaim tirelessly that God does not exist. Great scholars of the Christian text have discovered that the Founder said almost nothing attributed to Him. Histories are rewritten to redefine the only civilization that has ever brought mercy and freedom as the great source of cruelty and slavery. Great numbers of the officers of the Church have been persuaded to the middle way.

But in spite of these unending, desperate demonic efforts, tonight parents will kneel with their children and begin, “Our Father, Who art in Heaven . . . ” On the first day of the week, very large numbers of inhabitants of the planet Earth, from Rheims to Patagonia and from Murmansk to the Seychelles, will be reminded that Jesus said, “Take and eat. This is My Body.” This will occur with clarity and surpassing beauty in a grand liturgy on the Esquiline in Rome; it will occur in dilute reminiscences of the original in crystal cathedrals and tabernacles of hope. But neither the number nor the style matter as much as the fact. On another day a graduate of some littoral academic establishment, carefully inoculated with a diet of gentle professorial derision against the Galilean superstition, will unaccountably become a Carthusian or a Franciscan. Somewhere someone, the words of Jesus at the edge of awareness, will forgive, love, chose fidelity, have regard for the least, not despair of purity, deny himself, and take up his cross. These actions are the one great civilization. It must be remembered. It may also be seen.

Leave a Reply