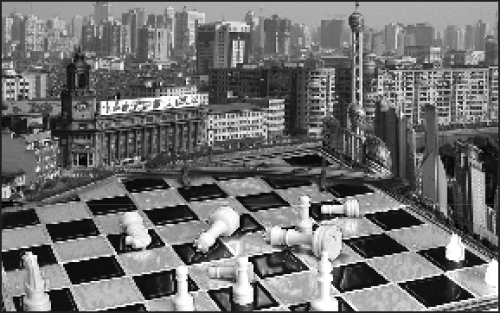

Anyone who doubts that China is rising fast as the new power in Asia need only take the ride I took last fall through Shanghai, from the Hongqiao International Airport to the Bund area along the Huangpu riverfront. It was just after dark, and this mammoth city was lit up in an awesome display the likes of which I had not seen even in Beijing. Shanghai has a skyline that puts New York and Chicago to shame, but then, Shanghai has a larger population than New York and Chicago combined. Mile after mile of new high-rise office buildings, many boasting the names of the world’s major corporations, stun the viewer with their proclamation of wealth and power. Unlike the boxy concrete-and-steel designs in Tokyo, the Shanghai skyline is marked by some of the most beautiful urban architecture I have ever seen.

And that was before I saw Pudong, the new economic area on the other side of the river. I took a boat tour to get a better look at this new economic-development zone. It is already crammed with office towers and factories. One impressive complex is the new Krupp steel plant. Another is the Jinmao Tower, the third-tallest building in the world. It is an impressive 88-story office complex, but even more noteworthy is the forest of other towers around it. In the Shanghai-Pudong area, over 300 high-rise buildings of 40 stories or more have been completed in the last five years, and the new structures are much more massive than what existed before. With these grandiose designs, China is clearly sending a message to the world that she is playing for keeps.

American security concerns have been focused on terrorism and the Middle East. That is understandable. Muslim terrorists are plotting more American deaths and must be combated. Yet terrorism is the weapon of the weak. It cannot change the global balance of power. And Islamic fundamentalism is a backward-looking doctrine of social and economic stagnation.

It is the rise of China that poses the greatest challenge to America’s position in the world. Endowing an empire of 1.3 billion people with modern industry, technology, and capital gives the authoritarian central government in Beijing immense resources with which to support its ambitions. And what is driving China is the impassioned spirit of nationalism and the limitless energy of capitalism. The combination will rock the world.

For those who like to think in ideological terms, the emergence of capitalism in China is a good thing. China under Mao Tse-tung had been one of the most extreme examples of the totalitarian pursuit of a new Socialist Man. Tens of millions died in the process. In his last days, Chairman Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution that did much to wipe out what material progress had been made in a mad attempt to reconnect with an imagined Chinese peasantry. Only with his passing were reformers under Deng Xiaoping able to start to open up the economy. But the reforms have only served to move China from communism to fascism. The massacre of demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989 has been followed by an even more important development: the fusing of commercial and patriotic zeal behind the drive to make China the most powerful country in the world.

Australian scholar Geremie R. Barme, who spent over 20 years in China and Hong Kong, described the new mood in his 1999 book In the Red. His work is built around the essay “To Screw Foreigners Is Patriotic,” in reference to the symbolism used in much of Chinese TV, movies, and novels, in which newly rich Chinese men buy the services of American prostitutes. The meaning is not just literal but applies to dealing with a decadent West in politics and economics. Barme writes of the rising middle class:

As the children of the Cultural Revolution and the reform era come into power and money, they are finding a new sense of self-importance and worth. Some of them are resentful of the real and imagined slights that they and their nation have suffered in the past, and their desire for strength and revenge is increasingly reflected in contemporary Chinese culture.

He further observes, “Anti-American sentiments blossomed in the 1990’s and have mass appeal . . . even dissidents have taken them up, advocating reforms as the way to further increase China’s power in world affairs.”

Mao’s body remains on display in Tiananmen Square. In a museum across the street, still festooned with communist symbols, are new works of art that herald China’s ancient imperial past alongside scenes from World War II and the Civil War. Mao’s giant portrait still hangs over the entrance to the Forbidden City, where he is hailed not as a Marxist but as a nationalist who enabled China to stand on her own feet.

Those of us who grew up in the Cold War saw ideology as the basis for conflict. From this experience, many concluded that, when the Berlin Wall came down, the Soviet Union disintegrated, and China opened up to trade, the world was finally on the path to peace. But the “Marxist moment” was an anomaly. Capitalism has long been the natural form of economic organization—and the most productive. With the exception of the Soviet Union, whose decrepit socialist economy eventually proved its undoing, all the great powers of the modern world have been capitalist. The global empires of Portugal, Spain, Holland, England, France, and the United States were all driven forward by energies that were largely commercial. This was also true of Germany and Japan, whose entry into the arena triggered two world wars. This should not be surprising, as only wealthy powers can support grand ambitions. Capitalism is a doctrine of limitless competition and has been quite compatible with—and, indeed, has made possible—the expanding scale of modern warfare.

Military threats always loom largest in the public mind, and China is creating such a danger. My visits to Beijing and Shanghai were preludes to the real reason for my trip, which was to attend the Fifth Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai. Held every two years, this event has two purposes: to showcase China’s advancements and to attract American and other Western companies who want to sell technology to Beijing.

China’s space program was highlighted, from the capsule astronaut Yang Liwei used to orbit the Earth in 2003 to animated projections of how China plans to land on the Moon and exploit its resources. Most of the displays, however, were devoted to Chinese fighters, remotely piloted (unmanned) military aircraft, helicopter gunships, and missiles of all types.

It was clear from the displays that there is no segregation of civilian and military aviation activities. The Chinese aerospace industry is run by the state. Its largest agency is Aviation Industries of China I (AVIC I). Its displays featured, side by side, a variety of civilian airliners and its numerous military projects for fighters, bombers, military transports, trainers, and reconnaissance aircraft. Its sister organization, AVIC II, was split off in 1999 to create competition and improve management. It concentrates more on business jets, helicopters, and missiles. One display featured a row of cruise and air-to-air missiles under a large poster of a corporate jet, again showing the guiding Chinese principle of “Jun-min jiehe”—combine the military and the civil.

This principle was very evident as I strolled through the two halls devoted to American and Western firms trying to sell high-tech products to China. These firms are only supposed to be engaged on the civilian side of Chinese development. That line cannot be drawn, however, and it is doubtful that those marketing their wares in this booming market care.

Italian Deputy Minister of Defense Salvator Cicu was on hand for the signing of a coproduction agreement between Agusta Westland and AVIC II for a new helicopter project. Italy, along with France and Germany, has been pressing the European Union to lift its arms embargo on China. But this embargo has long been undermined by the sale of dual-use equipment and technology to Beijing. Helicopters are a prime example. Why else would a defense official be celebrating an allegedly civilian project?

One display showed two virtually identical remotely piloted helicopters. One was configured for crop dusting; the other, for military reconnaissance. It did not take much imagination to consider what the crop duster might also be used for if armed with chemical or biological weapons.

American companies have been just as guilty as their European counterparts in helping China improve her capabilities. Boeing had a large mural at its booth touting not only how many airliners it had sold to China but how much production work it had outsourced to Chinese industry, how many Chinese engineers and technical workers it had trained, and how much it has invested in Chinese research facilities.

The mural also claims, “Boeing leadership in the U.S. business community and hard work with the U.S. Congress results in granting permanent normal trade relations with China.” PNTR assured Beijing an open American market for its exports, which account for the largest bilateral trade deficit in the grossly unbalanced U.S. international accounts. In reading this statement, I was reminded of a comment by James Sasser, a U.S. ambassador to China during the Clinton administration: “The Chinese really don’t do any lobbying. The heavy lifting is done by the American business community.” Of the Fortune 500, over 400 have set up operations in China. According to Ian Davis, the worldwide managing director of the consulting firm McKinsey & Company, China is “absolutely center stage right now” for Fortune 500 executives.

Like drug addicts who, in their lucid moments, understand the destructive consequences of their actions, some businessmen do notice where they are going even if they seem powerless to resist. Before he became President Clinton’s treasury secretary, Robert Rubin was cochairman of Goldman Sachs, a major financier of Chinese projects. He recently told the Associated Press that “China is likely to be the largest economy in the world and a tough-minded geopolitical power equal to any other geopolitical power on the globe.” And when this happens, it will be the direct result of the policies Rubin and others like him followed in both private and public service.

The contest may not come to a military showdown. The economic changes may be so large that America will simply back down whenever there is a confrontation. The economic changes determine what resources governments can mobilize to advance or protect national interests. Wars, when they occur, test whether the changes have been sufficient to reorder how the world is run and whose decisions matter.

In Shanghai, I stayed at the Broadway Mansions hotel in the Bund. The Bund is the area where the European powers had their offices when they ran China’s affairs. The British were the most powerful of the imperialist powers, and Broadway Mansions was built by a British businessman in the 1930’s when England was still considered the leading global superpower.

Today, Britain no longer holds that position in the world hierarchy or in Chinese affairs. In 1999, there was no serious thought given in London to holding on to Hong Kong. This beautiful city of free and prosperous people was handed over to the Beijing dictatorship without a whimper. The balance of power had obviously changed from what it had been in 1842, when England first laid claim to Hong Kong, or in 1945, when London reclaimed the city after it had been captured by Japan at the outbreak of World War II.

The British were on the winning side of both world wars. Indeed, England has not lost a major war since the Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. But they still declined as their economy fell out from under their empire. And the danger to us is that we have embraced classical-liberal economic notions about “free trade” and the neglect of international economic strategy that have their origins in 19th-century British thought.

Economic strategy is at the top of Beijing’s agenda—the core of its pursuit of “comprehensive national power.” Zhuhai, like Pudong, is a designated economic-development zone. It has a new international airport, about 25 miles from the port city. There is an eight-lane superhighway running from the city to the airport, mainly through farmland with very little traffic. But there are massive housing projects built (and building) for the expected future workforce. Near the city, new factories line the highway. A friend of mine who attended the fourth Aviation Expo noted that, where there had been a single line of factories two years ago, the plants are now two to four deep along the road.

The first challenge China poses is economic. It goes beyond the lopsided trade imbalance that is menacing American domestic industry and the value of the dollar as the international medium of exchange. The longer-term threat is from the vast new wealth and array of modern capabilities that will be available to a regime whose strategic ambitions clash with those of the United States—and not just in Asia.

In mid-November, Chinese President Hu Jintao took a nearly two-week trip through Latin America. His first stop was Brazil, for a five-day visit. There, he met with leftist President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva to renew the “strategic partnership” that had been forged during Lula’s visit to China the previous May. “China helped us send satellites to orbit and we, in return, offered techniques to China in the manufacture of airplanes,” said Lula. Both leaders predicted that China would replace the United States as Brazil’s top trading partner.

As a prelude to President Hu’s visit, the two countries entered into a military-cooperation deal on October 22. Signed in Brasilia by Brazilian Defense Minister Jose Viegas and visiting Chinese Defense Minister Cao Guangchuan, the agreement provides for military exchanges and logistical and scientific cooperation and also establishes a joint defense committee. China’s aid to Brazil’s long-range missile program, under the guise of satellite launches, will likely extend to other high-tech projects. Brazil’s nuclear-weapons program was halted in 1990 after a decade of secret work, but Lula’s renewed interest in nuclear power, including a new uranium-enrichment plant, has raised fears that the program may be restarted.

At the May summit between Hu and Lula, a joint statement was issued insisting “on the democratization of international relations and global multi-polarization.” This has long been Chinese terminology for ending American preeminence in world affairs, or what Beijing calls U.S. “hegemony.” At the November summit, Hu pledged Beijing’s support for Brazil’s bid to gain a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council.

From Brazil, Hu went to Argentina, where another “strategic partnership” was declared, backed up by the promise of $20 billion in investments in Argentina over the next decade to develop railways, telecommunications, hydrocarbon fuels, and space technology. Hu’s trip concluded with visits to Chile and Cuba. With left-leaning governments in power throughout most of Latin America, China is taking advantage of the same opportunities that the Soviets tried to exploit, only with a better set of tools forged by the ravenous growth of Beijing’s economy.

Washington must concentrate on enlarging and sustaining its own capabilities—industrial, technological, military, and financial—to ensure that it stays generations ahead of China. This will take more effort than was needed to defeat the Soviet Union, as Chinese capitalism is a much more vigorous contender than was Russian communism. But safeguarding America’s preeminence is just as imperative, regardless of the nature of the threat.

Leave a Reply