In the Afterword to the third edition of The Pilgrim’s Regress, C.S. Lewis argued that Romanticism had acquired so many different meanings that it had become meaningless. “I would not now use this word . . . to describe anything,” he complained, “for I now believe it to be a word of such varying senses that it has become useless and should be banished from our vocabulary.” Pace Lewis, if we banished words because they have multifarious meanings or because their meanings are abused or debased by maladroit malapropism, we should soon find it impossible to say anything at all! Take the word love. Few words are more abused, yet few words are more necessary to an understanding of ourselves. John Lennon and Jesus Christ do not have the same thing in mind when they speak of love. One puts a flower in his hair and goes on an hallucinogenic trip to San Francisco; the Other wears a crown of thorns and goes to His death on Golgotha.

Of course, C.S. Lewis understood this—so well that he wrote a whole book on the subject. In The Four Loves, he sought to define love. And what is true of a word such as love is equally true of one such as Romanticism. If we are to advance in understanding, we must abandon the notion of abolishing the word and commence, instead, with defining our terms. Lewis, in spite of his protestations, understood this also, proceeding from his plaintive call for the abolition of the word to the enumeration of various definitions of it, claiming that “we can distinguish at least seven kinds of things which are called ‘romantic.'” From four loves to seven romanticisms, Lewis was not about to abandon meaning, or the mens sana, to men without minds or chests.

Since Lewis’s seven separate definitions of Romanticism are a little unwieldy, it is necessary to hone our definition. According to the Collins Dictionary of Philosophy, Romanticism is “a style of thinking and looking at the world that dominated 19th century Europe.” Arising in early medieval culture, it referred originally to tales in the Romance languages about courtly love and other sentimental topics, as distinct from works in classical Latin. From the beginning, therefore, Romanticism stood in contradistinction to classicism. The former referred to an outlook marked by refined and responsive feelings and, thus, could be said to be inward looking, subjective, “sensitive,” and given to noble dreams; the latter is marked by empiricism, governed by science and precise measures, and could be said to be outward looking.

Society has oscillated between the two visions of reality represented by classicism and Romanticism. This is itself an aberration, a product of modernity. In the Middle Ages, no such oscillation between these two extremes of perception. On the contrary, the medieval world was characterized by a theological and philosophical unity that transcended the division between Romanticism and classicism. The nexus of philosophy and theology in the Platonic-Augustinian and Aristotelian-Thomistic view of man represented the fusion of fides et ratio, the uniting of faith and reason. Take, for example, the use of the figurative or the allegorical in medieval literature, or the use of symbolism in medieval art. The function of the figurative in medieval art and literature was not intended primarily to arouse spontaneous feelings in the observer or reader but to encourage him to see the philosophical or theological significance beneath the symbolic configuration. In this sense, medieval art, informed by medieval philosophy and theology, is much more objective and outward looking than the most “realistic” examples of modern art. The former points to abstract ideas that are the fruits of a philosophical tradition existing independently of either the artist or the observer; the latter derives its “realism” solely from the feelings and emotions of those “experiencing” it. One demands that the artist or the observer reach beyond himself to the transcendent truth that is out there; the other recedes into the transient feelings of subjective experience. The surrender of the transcendental to the transient, the perennial to the ephemeral, is the mark of post-Christian—and, therefore, post-rational—society. It is the mark of the beast.

The medieval fusion of faith and reason was fragmented, theologically, by the Reformation and, philosophically, by the neoclassicism of the late Renaissance. Romanticism and classicism can be said to represent attempts to put the fragments of post-Christian humpty-dumptydom together again. They are attempts to make sense of the senselessness of fragmented faith and reason.

The superciliously self-named Enlightenment was the philosophical Phoenix-Frankenstein that arose from the ashes of this fragmented unity. It represented faithless “reason” or, more correctly, a blind faith in “reason” alone. In much the same way that the theological fragmentation of the Protestant Reformation had led to a rejection of scholastic ratio, enshrining fides alone, so the philosophical fragmentation of the Renaissance-Enlightenment had led to a rejection of fides, enshrining ratio alone. A belief that man had dethroned the gods of superstition led very quickly to the superstitious elevation of man into a self-worshiping god. Eventually, it led to the worship of the goddess Reason at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris during the Reign of Terror.

If the Enlightenment was characterized by scientism and skepticism —i.e., the worship of science and the denigration of religion—the Romantic reaction to the Enlightenment was characterized by skepticism about science and by the resurrection of religion. Romanticism would emerge, in fact, as the reaction of inarticulate “faith” against inarticulate “reason” —heart worship at war with head worship. It was all a far cry from the unity of heart and head that had characterized Christian civilization. The Romantic reaction would, however, be a significant step in the right direction, leading many heart-searching Romantics to the heart of Rome. This was, at least, the case in England and France, though, in Germany, it led (via the genius of Wagner and the madness of Nietzsche) to the psychosis of Hiter.

Arguably, the Romantic reaction in England began in 1798 with the publication of Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Published only nine years after the French Revolution, the poems in Lyrical Ballads represented the poets’ recoil from the rationalism that had led to the Reign of Terror. Wordsworth passed beyond the “serene and blessed mood” of optimistic pantheism displaved in his “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” to a full embrace of Anglican Christianity, as exhibited in the allegorical depiction of Christ in “Resolution and Independence.” Coleridge threw down the allegorical gauntlet of Christianit)’ through the sublimation of the subliminal in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”; in his “Hymn Before Sunrise in the Vale of Chamouni,” he saw beyond majestic nature (O Sovran Blanc’.) to the majesty of the God of nature:

Who made you glorious as the Gates of Heaven

Beneath the keen full moon? Who bade the sun

Clothe you with rainbows? Who, with living flowers

Of loveliest blue, spread garlands at your feet?—

God! let the torrents, like a shout of nations,

Answer! and let the ice-plains echo, God!

God! sing ye meadow-streams with gladsome voice!

Ye pine-groves, with your soft and soul-like sounds!

And they too have a voice, yon piles of snow.

And in their perilous fall shall thunder, God!

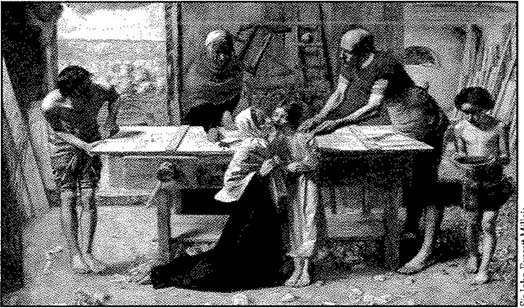

In their poetry, Wordsworth and Coleridge had leapt over the errors and terrors of the previous three centuries to rediscover the purity and passion of a Christian past. This pattern would be repeated in the various manifestations of neo-medievalism that would follow in the wake of Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s Romanticism. The Gothic Revival, heralded by the architect Augustus Pugin in the 1830’s and championed by the art critic John Ruskin 20 years later, attempted to discover a purer aesthetic through a return to medieval notions of beauty. The Oxford Movement, spearheaded by John Henry Newman, Edward Pusey, and John Keble, sought a return to a purer Catholic vision for the Church of England, b)passing the Reformation in an attempt to graft the Victorian Anglican Church onto the Catholic Church of medieval England through the promotion of Catholic liturgy and a Catholic understanding of the sacraments. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, formed around 1850 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and others, looked to a purer vision of art in the clarity of medieval and early Renaissance painting that existed, they believed, before the innovations of Raphael.

Perhaps the most important poetic voice to emerge from the Romantic reaction is that of Gerard Manley Hopkins, who was received into the Catholic Church by John Henry Newman in 1866, 21 years after Newman’s own conversion. Influenced by the pre-Reformation figures of Saint Francis and Duns Scotus, and by the Counter-Reformation rigor and vigor of Saint Ignatius Loyola, Hopkins wrote poetry filled with the dynamism of Catholic orthodoxy. Unpublished in his own lifetime, Hopkins was destined to emerge as one of the most influential poets of the 20th century following the first publication of his verse in 1918, almost 30 years after his death.

Although these manifestations of Romantic neo-medievalism transformed 19th-century culture, countering the optimistic and triumphalistic scientism of the Victorian imperial psyche, it would be wrong to imply that Romanticism always led to medievalism. The neo-medieval tendencies of what might be termed Light Romanticism were paralleled by a Dark Romanticism, epitomized by the life and work of Byron and Shelley, which tended toward nihilism and self-indulgent despair.

If Wordsworth and Coleridge were reacting against the rationalist iconoclasm of the French Revolution, Byron and Shelley seemed to be reacting against Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s reaction. Greatly influenced by Lyrical Ballads, they were nonetheless uncomfortable with the Christian traditionalism that Wordsworth and Coleridge began to embrace. Byron devoted a great deal of the Preface to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage to attacking the “monstrous mummeries of the middle ages,” and Shelley, in his “Defense of Poetry,” declared his loathing of Tradition by insisting that poets were slaves to the Zeitgeist and “the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present.” Slaves of the spirit of the present and mirrors of the giant presence of the future, poets were warriors of Progress intent on vanquishing the superstitious remnants of Tradition. Perhaps these inanities could be excused as being merely the facile follies of youth, especially as there appeared to be signs that Byron yearned for something more solid than the inarticulate creedless deism espoused in “The Prayer of Nature” and indications also that Shelley’s militant atheism was softening into skylarking pantheism. Their early deaths, and the early death of their not-so-dark friend Keats, cut them off in the very life throes of their groping for the light of meaning in the darkness of their self-centered and self-defeating grappling. Stealing upon them like a thief in the night, death has preserved them forever as icons of folly who often, almost in spite of themselves, attained heights of beauty and perception.

In comparing Wordsworth and Coleridge with Byron and Shelley, we see a parting of the ways between the high road of Light Romanticism and the low road of the Dark Romantics. Yet it would be wrong to assume that the parting of the ways was permanent and that, as with Kipling’s East and West, “never the twain shall meet.” The two roads of Romanticism have more in common with the high road and the low road that lead to the “bonny, bonny banks of Loch Lomond,” or, perhaps more appositely, they converge at last where all roads lead —at Rome. For, as befits a romance, Romanticism, even Dark Romanticism, often leads to Rome. The Byronic influence of Dark Romanticism crossed the channel and found itself baptized in the decadence of Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Huvysmans, all of whom plumbed the depths of despair, discovered the reality of Hell, and fled in horror into the arms of Mother Church. Baudelaire was received into the Church on his deathbed, Verlaine converted in prison, and Huysmans, having dabbled with diabolism, ended his life in a monastery. The principal difference between the Dark Romanticism of Byron and Shelley and the decadence of Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Huysmans is that the former delved into the darkness of their own egos with nothing but Nothing to illumine their musings, whereas the latter delved deep into their own inner darkness with the light of theology. The former were lost in circumlocutions of self-centered circumnavigation; the latter discovered the Beast that dwelt in the bottomless pit of self-obsession and, beating their chests, knelt at last before the Christ Whom their own sins had crucified. The French decadence was also characterized by its preoccupation with symbolism, which was itself a return to the mode of communication employed in medieval art.

If Dark Romanticism had crossed the channel in Byronic guise, metamorphosing into the symbolism of the French decadence, it returned under the patronage of Oscar Wilde, who was an aficionado of Baudelaire and Verlaine. Somewhat bizarrely and perhaps perversely, Wilde had read Huysmans’ recently published decadent masterpiece, A Rebours, during his honeymoon in Paris, a novel that would greatly influence his own decadent tour de force, The Picture of Dorian Gray. As with their French predecessors, the doyens of the English decadence also found their way to the Catholic Church, turning their back on debauchery and modernity in favor of traditional Christianity. Apart from Wilde himself, who was received into the Church on his deathbed, other leading figures of the English decadence who became Catholic include Aubrey Beardsley, Lionel Johnson, John Gray, Ernest Dowson and even the enfant terrible of the 1890’s, Lord Alfred Douglas. The high road and the low road converged into the Roman road of conversion. The high road of sanctity was followed by such as New man and Hopkins, both of whom became Catholic priests, whereas the low road of sin, the path of the Prodigal Son, was taken by a host of French and English Decadents. For, as Oscar Wilde never tired of reminding us, even the saints were sinners, and all sinners are called to be saints.

Leave a Reply