Speaking on CNN’s “State of the Union” recently, House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn likened President Donald Trump to Benito Mussolini. The South Carolina lawmaker opined that Trump “plans to install himself in some kind of emergency way to continue to hold on to office.”

“The American people had better wake up,” Clyburn declared. “I know a little bit about history, and I know how countries find their demise. It is when we fail to let democracy—the fundamentals of which is a fair, unfettered election, and that’s why he is trying to put a cloud over this election, floating the idea of postponing the elections…”

Clyburn’s concoction is a far cry from how Mussolini actually seized power in 1922 when he marched on Rome. In truth, the closest America has come to Mussolini is not Donald Trump, but Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

For one, FDR had Il Duce’s taste in aesthetics. Compare Mussolini’s “Fascist” architecture and the New Deal-era Federal buildings erected between 1934 and 1940 in Washington DC.

Beyond the important sphere of aesthetics, FDR and Mussolini were strikingly similar in political temperament. Both liked strong, centralized government structures, unfettered by the judiciary. Both were accomplished demagogues, using new communication technologies—film and radio—to get their message across. Both sought to resolve the problem of class conflict through the mechanisms of the corporate state.

As I wrote in Chronicles two decades ago, in the end FDR turned out to be a more toxic figure than Il Duce. His legacy has been more lastingly harmful to the social and moral fabric of the United States than Mussolini’s was to Italy. Roosevelt was a more efficient and more successful fascist than the inventor of fascism himself.

It is worth recalling that Mussolini was hailed as a genius on both sides of the Atlantic because of his economic and social policies which saved Italy from the Great Depression. Roosevelt and his “Brain Trust,” the architects of the New Deal, were fascinated by fascism, a term which was not perjorative at the time. They saw it as a form of economic nationalism built around consensus planning by a powerful technocratic elite in government, business, and labor.

The New Dealers were unconcerned with Mussolini’s rejection of democracy. “The wops are unwopping themselves,” Fortune magazine noted with awe in 1934. State Department roving Ambassador Norman Davis praised the successes of Italy in remarks before the Council on Foreign Relations in 1933, speaking after the Italian ambassador had drawn applause from his distinguished audience for his description of how Italy had put its “own house in order… A class war was put down.” Roosevelt’s ambassador to Italy, Breckenridge Long, was enthusiastic for the “new experiment in government” which “works most successfully.” Henry Stimson, secretary of war under Roosevelt, found Mussolini “a sound and useful leader.” FDR shared such views of “that admirable Italian gentleman,” as he termed Mussolini in 1933.

The most radical aspect of the New Deal was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), passed in June 1933, which set up the National Recovery Administration. Most industries were forced into cartels. Codes that regulated prices and terms of sale transformed much of the U.S. economy. The industrial and agricultural life of the country was to be organized by government into vast farm and industrial cartels. This was corporatism, the essence of fascism.

The liberal historian Charles Beard freely admitted that “FDR accepts the inexorable collectivism of the American economy… national planning in industry, business, agriculture and government.” But detractors existed even within his own party. Sen. Carter Glass (D-Va.) denounced the NIRA as “the utterly dangerous effort of the federal government at Washington” to transplant fascism to America.

The experiment worked admirably. FDR’s New Deal united communists and fascists. Union leader Sidney Hillman had praised Lenin as “one of the few great men that the human race has produced, one of the greatest statesmen of our age and perhaps of all ages.” Big-business partisan Gen. Hugh Johnson wanted America to imitate the “dynamic pragmatism” of Mussolini. Together, Hillman and Johnson developed the National Labor Relations Board. They shared a collectivist and authoritarian aversion for the legacy of the Old Republic.

Like fascist and communist dictators, Roosevelt relied on his charisma, carefully and deceitfully developed, and the executive power of his office to stroke the electorate into compliance and to bludgeon his critics. His welfare projects went far beyond aid to the poor and wound up bribing whole sectors of American society—farmers, businessmen, bankers, intellectuals—into willing dependence on him and the state he created. Through subsidies, wrote Richard Hofstadter, “a generation of artists and intellectuals became wedded to the New Deal and devoted to Rooseveltian liberalism.”

The only practical difference between FDR and Mussolini was that the former was far less successful in resolving the economic crisis. When he was elected, there were 11.6 million unemployed; seven years later, there were still 11.3 million out of work. In 1932, there were 16.6 million on relief; in 1939, there were 19.6 million. Only the war ended the depression.

As for the war, during the campaign of 1940 FDR repeatedly promised to keep the country out of it—and then did everything to do the opposite. In March 1941, he rammed the Lend-Lease Act through Congress, although selling munitions to belligerents and conveying them were illegal acts of war. At the Atlantic conference FDR entered into an illegal agreement with Churchill that America would go to war if Japan attacked British possessions in the Far East. This was an impeachable offense. He also allowed undercover British agents to operate freely and illegally within America.

What’s more, FDR’s belligerency toward the Japanese as well as the Germans helped cause the attack on Pearl Harbor (of which he may well have been fully aware in advance) even as he vilified and persecuted the critics of his policies as “Nazis” and “traitors.”

FDR’s war legitimized the emergence of the U.S. as a global power. Between 1941 and 1945, Washington became the command-and-control center of the ultra-centralized, unitary state that to this day seeks to maintain full-spectrum global dominance. Just as the New Deal created the federal Leviathan and destroyed those vestiges of the Old Republic that had survived Lincoln, FDR’s war turned America into a “superpower” obliged to carry the burdens of empire forever, or until it destroys itself.

“It seems to me,” wrote H.L. Mencken in his diary on April 13, 1945, one day after FDR’s death, “to be very likely that Roosevelt will take a high place in American popular history—maybe even alongside Washington and Lincoln… He had every quality that morons esteem in their heroes.” FDR built a cult of personality just as Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin did. His power depended on it. His continuing sainthood is unsurprising. “He was the first American,” wrote Mencken, “to penetrate to the real depths of vulgar stupidity. He never made the mistake of overestimating the intelligence of the American mob.”

When Mussolini left the stage, the Italian nation was still its old self. Over two decades of fascism had left Italian society and its key institutions—family, the Church, education, arts, culture, local communities—largely intact, or even strengthened. In the end, Il Duce was much smoke and little fire, too civilized to murder political opponents, or to re-engineer the country.

Until Nazi Germany occupied Italy in September 1943, that is. To his discredit, for the final 19 months of the war Mussolini was the titular head of the German-controlled Salò Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana). It was a puppet state which did kill people on a mass scale, including Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Ciano. He nevertheless remains a folk hero to millions of Italians of all classes and regional allegiances.

Il Duce’s memorable slogan, meglio vivere un giorno da leone che cent’anni da pecora—“better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep”—should resonate, today, with all those Americans who are threatened with physical extinction if they do not accept the status of despised helots in the land their ancestors had created from nothing.

FDR left the stage only weeks before Mussolini was summarily shot by communist partisans. His legacy is alive and well, 75 years later. It is visible in the destruction of America’s legal order, social and ethnic cohesiveness, as well as in the crisis of families, faith, tradition, education, arts, culture, and local communities.

Clyburn and his ilk love all that. Therefore they should not try to disparage their contemporary foes by comparing them to Mussolini. After all, he was FDR’s uncelebrated role model.

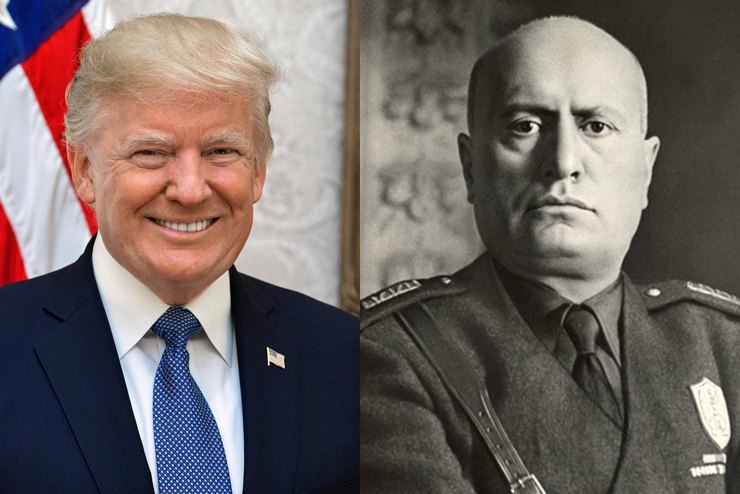

Image Credit:

above (from left to right): Donald Trump and Benito Mussolini [Trump image by: Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead. Mussolini image by: Pictorial Press Ltd / via Alamy Stock Photo]

Leave a Reply