Some time around 800 b.c., Homer put the heroic tales of the Achaeans into lyric form: battles, expeditions, adventures, conquests. The tales were inspiring, heroic, tragic, triumphal. Greeks recited Homer’s iambic pentameter for centuries; so, too, did we as schoolchildren—as inheritors of Western civilization. We Americans, however, also have our own Homeric Era. While the Greeks moved from north to south through their peninsula and eventually into the Peloponnesus, Americans moved from east to west across the continent and eventually into California. Recalled most vividly, though, is the trans-Mississippi West. That’s where the mountain men trapped beaver, the miners struck gold, the cowboys drove cattle, the cavalry fought Indians, the magnates of industry built railroads, the gunfighters dueled.

The pioneers of the trans-Mississippi West came from every corner of the United States: puritanical Yankees from New England, cavaliers from the Old South, Pennsylvania Dutch from the Susquehanna Valley, and Scotch-Irish frontiersmen from the length and breadth of the great Appalachian range. They also came from overseas: Dutchmen from Germany; Scandinavians from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden; Limeys from England; Welshmen from Wales; Cousin Jacks from Cornwall; Highlanders and Lowlanders from Scotland; and, in the greatest numbers, Mikes and Pats from Ireland’s Old Sod. There were others, too, but the great bulk of pioneers were the product of internal migration or immigration from northwestern Europe. Celtic and Germanic tribesman had trekked, generation by generation, from central Asia to the British Isles. In America, these same peoples would move in a powerful wave from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Their fights, discoveries, tragedies, adventures, and conquests would rival anything the ancient Greeks could offer. It is not surprising that Westerns became a staple of movie production during the silent era—we were watching ourselves conquer a continent and build a new civilization. There was something else, though. We were returning to a raw wilderness that excited the senses for the very reason that it had not yet been conquered. It was threatening and dangerous—and it was wide open for those with grit, perseverance, and spirit. There was a decline in Westerns when talkies were first introduced, but once outdoor sound recording was improved, the Old West came roaring back on the silver screen. Many of these movies during the 1930’s were low-budget or B-Westerns. John Ford changed all that with Stagecoach in 1939.

Stagecoach may be my favorite Western. Back in the mid-1980’s while teaching the American West at UCLA, I was interviewed by a Canadian journalist for an article he was writing on the 19th-century frontier. As an aside, he asked me to list my ten favorite Westerns. He caught me off guard—I had never really given it much thought. I paused for a few seconds, trying to recall my favorites, and then told him I would attempt to list them chronologically; off the top of my head, I couldn’t possibly order them by precedence. Stagecoach was the earliest favorite I could recall. When I had finished, I had a baker’s dozen. I couldn’t stop at ten. All these years later, I still have the same baker’s dozen, and I still don’t think I could order them by precedence, although, with a gun put to my head, I would narrow the list to Stagecoach and The Searchers, both products of John Ford’s genius.

Admittedly, listing favorite Westerns is a highly subjective exercise. However, I think there are some objective criteria that can be applied when evaluating a Western. Does the movie have grand vistas that reveal not only the spectacular beauty of the West but the raw power of nature? Is there a musical score that sweeps us away to another time and place, plucks the chords of our ancestral soul, and helps tell the story? Are there mustangs, Appaloosas, paints, and quarter horses, and stunts with horses that remind us that real cowboys found work in Hollywood? Are rifles and revolvers common but cherished tools? Does the movie capture the spirit of the times and the character of the people? Are such values and characteristics as courage, perseverance, optimism, hospitality, fair play, deference to women, and loyalty to kith and kin on display and integral to the story? Are the characters well developed, and are there those we can empathize with and root for? Not all of my favorite Westerns have every last one of these ingredients, but those that do not are so outstanding in most ways that their flaws are overwhelmed.

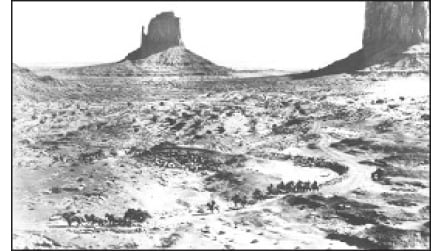

Although The Vanishing American, a silent movie released in 1925, gave many Americans their first glimpse of Monument Valley, a natural wonder on the border of Utah and Arizona, it was Stagecoach and John Ford’s many other Westerns that made it famous. Ironically, a minor but surprising flaw in Stagecoach is an abrupt and impossible change of scenery when John Wayne, as the Ringo Kid, suddenly appears standing in the path of the stage, twirling his rifle. Behind him is Monument Valley. In front of him is the stage, incongruously framed by the chaparral and rocks of California’s coastal hills. Less jarring is the Indian attack on the stage while it crosses a dry lake bed not in Monument Valley but in the California desert. But these are minor objections to a masterpiece. As soon as the film begins to roll and the music plays, no matter how many times I have seen Stagecoach, goose pimples ripple up and down my spine. I’m looking at the Lordsburg stage rolling down an endless track of dirt in Monument Valley—these are the wide-open spaces I long for—and listening to lyrical chords that put me in the Old West. In seconds, I forget I’m watching a movie. It’s a grand adventure, and I’m part of it.

Dialogue is sparse and crisp. The telegrapher hands a message hot off the wire to an Army officer. He reads it and says only, “Geronimo.” The grim expressions on the faces of others in the telegrapher’s office tell us all we need to know. John Ford thought the camera should tell the story. (If only other directors understood this.) Ford also wanted his characters to look the part. Whenever he could, he simply hired real teamsters and cowboys and real Indians to appear in his movies. As the stage rolls into town in one of the movie’s first scenes, the camera focuses on three cowpokes moseying down the wooden sidewalk. They are rail thin, taut skinned, sunburned, leathery, bow legged, and half limping—and they came off an Arizona ranch. I feel like I’m looking at an old sepia-tone photo from 1880. The Indians in the movie are Indians, although Navajo and not Apache as portrayed. Ford employed Navajo in his movies again and again. They named him Natani Nez, the Tall Leader, and made him an honorary chief. The most prominent promontory in Monument Valley is called John Ford’s Point.

Though not Plains Indians, the Navajo were good horsemen. Nonetheless, the trick riding and falls from horseback in Stagecoach are performed by white stuntmen in Indian costume—most notably, “Yakima” Canutt. Because of his nickname, Enos Edward Canutt was thought by some to be part Indian. Actually, he was German and Irish, and born and reared in the Yakima River country of Washington. He is seen throughout Stagecoach and performs the most spectacular stunt in the movie when he leaps from his paint war pony onto the six-horse team pulling the stage. Real Indians would never have done this—they would have shot the horses, bringing the chase to a quick end—but the stunt set the standard for the industry. Canutt also plays the buckskin-clad cavalry scout who gallops into view in the movie’s first scene with Winchester held high in his right hand. A frozen frame of the scene would look like a Frederick Remington or Charles Russell painting. It is not coincidental. Ford was a fan of both artists and framed many of his shots to look like their paintings.

Throughout Stagecoach, America’s folk melodies ebb and flow, most prominently the melody commonly associated with “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie,” although several other songs have been put to the same music. Other melodies we hear are associated with the songs “Joe Bowers,” “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair,” “Lilly Dale,” “Gentle Annie,” and “Rosa Lee.” They are melodies that we, as Americans, hold in our hearts—or at least did until the last quarter of a century or so. They are our tradition and express our soul. Music in Stagecoach introduces, accents, and even carries scenes. For long periods, the passengers on the stage sit silently, the music explaining all. All the human emotions are expressed in the notes and chords of the movie’s score, which won an Academy Award. “For John Ford, there was no need for dialogue,” said Jimmy Stewart. “The music said it all.” Stewart was exaggerating, of course, but no director has ever used music so effectively as did Ford. The great director himself said that he would “rather have good music than bad dialogue.” Perhaps music has a more powerful effect on me than it does on most, but my spirits rise and fall, turn light and dark, and I feel uplifted, vengeful, loving, or melancholy as melodies and tempos change.

The characters in Stagecoach, whether male or female, with a few exceptions, teach us how to behave. The men are flawed but ultimately strong; so, too, are the women. Louise Platt is the proper and pregnant wife of a cavalry officer. She appears at first as a pampered Southern belle unable to see beyond artificial class distinctions but evolves, grows, and gains strength scene by scene. Claire Trevor is the shopworn prostitute with the heart of gold, but also with the courage to face adversity and death. I have heard actresses in Hollywood and professors in academe in recent times proclaim that there were no roles for strong women in the old movies. Are these people entirely ignorant or so warped by political correctness that they are blind? Every Western is full of strong women—and that is the way it was in reality on the frontier.

As the corrupt banker, Berton Churchill shows us how not to behave. Not only does he abscond with depositors’ money, but he is more concerned with his own escape than with the safety of the women, an unforgivable sin on the frontier. Donald Meek, as the meek and mild liquor drummer, initially seems not much better. He is easily bullied and appears frightened by his own shadow. Later, though, he is one of those who makes protection of the women paramount. Likewise, Thomas Mitchell, as an alcoholic doctor, and John Carradine, as a professional gambler, rise to the occasion to perform heroically. As the voluble and bumpkin-like stage driver, Andy Divine serves as comic relief but, in the face of an Apache attack, he drives like Jehu until wounded. We have no doubt how George Bancroft, as the U.S. marshal, and John Wayne, as the Ringo Kid, will perform. For the time being, they are on opposite sides of the law, but both clearly live by the Code of the West: Their word is their bond; they pay great deference to women; and they prefer death to dishonor—or, as a Texas cowboy put it, “I’ll die before I’ll run.”

The travelers on the stage reflect the character of the people who led the American charge across the continent. A few who ventured onto the frontier were found wanting, but most set examples to inspire the rest of us. Once upon a time, we were expected to live up to their examples. This was long before the emasculated and effeminized man was celebrated by Hollywood.

Strong men and women, John Wayne, Monument Valley, and powerful, poignant music are again on display in The Searchers, released in 1956. Advances in technology and a big budget allowed John Ford to film in VistaVision, which produced the most brilliant colors and greatest clarity I had seen on the silver screen. As the credits roll, the Sons of the Pioneers sing “What Makes a Man to Wander,” with a melody that is beautifully melancholy. In the first scene, we watch from behind as Dorothy Jordan opens a cabin door to the strains of “Lorena.” A poignant ballad with a haunting melody that became popular during the Civil War, especially among soldiers—particularly Confederates—“Lorena” helps establish the character seen in the distance riding toward the cabin. His gray coat tells us the rest. He is John Wayne as Ethan Edwards, a Confederate Civil War veteran who hasn’t seen his brother, Aaron, in many years.

As Ethan begins to come into focus, Dorothy Jordan’s expression suggests that he is the brother she really loved. Aaron steps out of the cabin and stands next to his wife. Their children follow as if coming down the aisle of a church and moving laterally into pews. Ethan reaches the cabin and dismounts. The brothers look at each other and pause, their faces frozen, and then shake hands. Nothing more. They are men hardened by the Civil War and life on the frontier. No modern Hollywood hysteria. They turn and step toward the cabin door. Dorothy Jordan backs through the doorway, her eyes never off Ethan. All doubt about her true love vanishes.

John Ford has done it again. I am transported in seconds to the Texas frontier during the late 1860’s, and I’m participating in an epic drama. As in Stagecoach, music drives much of the movie and helps tell the story. The Indian enemy this time is the Comanche. They are played by Ford’s beloved Navajo. Modern viewers with their politically correct but wildly mistaken impressions of Indians might not appreciate Ford’s great affection for the American Indian. Ford understood the constant intertribal warfare and the rape, scalping, torture, slaughter, kidnapping, and slavery that was part of it—and that, when the white tribe came along, it was subjected to the same. Ford also understood that the Indian ultimately found himself overwhelmed by the far more powerful and technologically advanced white tribe, although the power of the new tribe was not so readily apparent upon initial contact on the frontier, where the Indian saw only small groups of whites. By Ford’s time, the Indian had been beaten and broken and reduced to living on reservations. With some notable exceptions, poverty and alcoholism were the norms. Ford could not help but compare the dispossession of the Indian to that of his own ancestors in Ireland.

In The Searchers, Ford does not shy away from the unspeakable savagery of the Comanche, although the camera never actually shows mutilated and dismembered corpses. Hollywood codes would not have allowed it. Even today, though, I suspect Ford would have left such carnage to our imagination, which may be more powerful. At the same time, Ford makes it clear that the Comanche were fighting the white tribe for what they considered theirs—what they took from other Indians—and they aimed to terrify and kill all challengers. That was simply as it always had been. Accommodation was only for the weak. Ford makes the chief of the Comanche band that Ethan is tracking an equal to the Duke. Chief Scar is played by 6’5″ powerful and handsome Henry Brandon. The German-born actor was anything but Indian, but with a wig of long black hair and war paint, he looks big, mean, and impressive. White stuntmen, as usual, also don Indian costumes and perform all the trick riding and stunts. At 60 years old, Yakima Canutt was too old and bruised for spectacular falls from horseback and was doing more stunt coordinating than stunts. In The Searchers, the best of the stunts are performed by Frank McGrath, although, at 52, he was no kid himself and had only recently got out of a body cast after breaking his back while performing a stunt. These great old cowboy stuntmen would have been right at home on the Long Drive to the Kansas cow towns, displaying the reckless bravado, irrepressible spirit, and presence of mind in the face of danger that endeared the cowboys of the 19th century to Americans.

Some argue that, in The Searchers, John Wayne shows his dark side for the first time in his career. They obviously have not seen Red River, released eight years earlier. Ethan Edwards does have his demons. He is a Civil War veteran and a frontiersman who has fought Comanche all his life and witnessed their savagery up close and personal like. Ethan is not a gentle man, and neither were the real men who won the West. He is on a mission, an Homeric odyssey that takes years and covers thousands of miles, to find his niece, Debbie, kidnapped by the Comanche, and avenge the horrific deaths of her family. If she has gone mad from Comanche abuse and rape—as portrayed by two other captives in the movie—or, after years of captivity, beginning when she was a little girl, she has become Comanche, it is suggested that he might kill her. His young sidekick on the mission is Debbie’s cousin, Martin Pawley, played by Jeffrey Hunter. Pawley is one-eighth Cherokee, and that one drop of blood bothers Ethan. Nonetheless, Ethan takes him under his wing, playing the role of a curmudgeonly mentor, a relationship that could be compared with the real-life relationship between director John Ford and actor John Wayne. Driven by whatever demons, Ethan is fiercely loyal to his kinfolk and to his tribe.

One of the great themes running throughout The Searchers is a paradox that has perplexed Americans since the colonial era. The movie ends with Ethan’s reunified extended family stepping into a ranch house. Ethan does not follow. Men like him who led the way West could not accept the civilization that came along behind. Daniel Boone saw the smoke from a neighbor’s cabin and left Old Kaintuck for Missouri. David Crockett was gone to Texas for a fresh start. Jim Bridger could not stand to go “down below” from his beloved Rocky Mountains.

While Stagecoach and The Searchers top my list, they have competition. The Westerner (1940) has simply brilliant interplay between Walter Brennan, as Judge Roy Bean, and Gary Cooper, as a cowboy mistaken for a horse thief. They Died With Their Boots On (1941) stars Errol Flynn at his best and portrays George Custer in a manner that would have elated his wife, Libby. Music drives the movie throughout, and nobody ever looked better than Flynn on a horse. Red River (1948) is the best portrayal of a cattle drive on the silver screen, and the Duke leads this one, becoming maniacal and homicidal along the way. Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950) make up John Ford’s cavalry trilogy, although the combination of movies was pure happenstance. Together, they are the greatest tribute to the U.S. Cavalry in cinematic history. They each have their many strengths and a few flaws. My wife favors Rio Grande because of Maureen O’Hara’s strong performance and her relationship with Wayne. Rio Grande also has the best music, including performances by the Sons of the Pioneers as regimental singers. Despite its portrayal of townsfolk acting like frightened sheep, High Noon (1952) features Gary Cooper at his best and Grace Kelly at her most beautiful. Katy Jurado telling Lloyd Bridges’ character, Harvey Pell, that “It takes more than big broad shoulders to make a man” might be one of the best-delivered lines ever in movies.

The Big Country (1958) has perhaps the best single scene ever shot that says everything about men and loyalty in the Old West. Watch the confrontation between Charles Bickford and Charlton Heston at the entrance to Blanco Canyon. It is arguably the best performance in Heston’s career, and one of the most moving sequences ever put on film. Directed by and starring Marlon Brando, One-Eyed Jacks (1961) almost went unnoticed when it was released. I don’t understand why. It knocked me out then, and it knocks me out today. If you can accept Steve McQueen, with his blond hair and watery blue eyes, playing a half-breed, then Nevada Smith (1966) will keep you glued to the screen. His performance is classic McQueen, and others, including Brian Keith and Karl Malden, could not be better. Completing my baker’s dozen is Paint Your Wagon (1969). Despite being a musical, it is absolutely the best depiction of mining-camp life ever put on the screen. This is Mark Twain and Bret Harte, part fun romp and part melancholy journey. Clint Eastwood can’t sing, but he is perfect in his role, and Lee Marvin is brilliant.

These Westerns—and others—offer a dramatic interpretation of our American West during its wild and woolly era. They are not meant to be documentaries, but they certainly capture the essence of the frontier experience, an experience that turned Europeans into Americans and left us with a tradition we can embrace with pride.

Leave a Reply