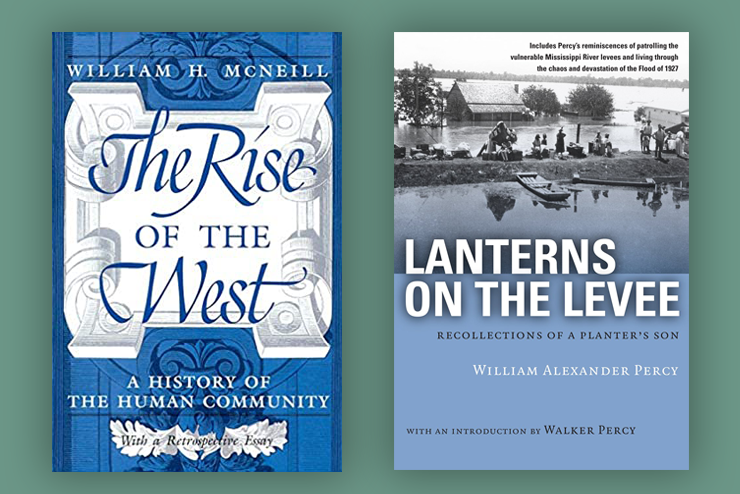

First the crazies tore down statues they deemed offensive. Next they vandalized churches. Then they demanded trigger warnings on classic movies like Gone with the Wind and Blazing Saddles. If these monsters ever discover libraries, books will be next. Let me suggest you hoard copies of William McNeill’s The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community (1963) before they shred them. In these savages’ simple minds, McNeill’s ethnocentric title alone will justify the book’s eradication. Even Chronicles’ readers may find McNeill’s conclusions insensitive at times, as when he wrote, “The loss to human culture involved in the Spanish extirpation of Amerindian civilizations does not therefore seem very great.”

McNeill’s tour de force covers Middle Eastern predominance up to 500 B.C., then focuses on Eurasia from then to A.D. 1500, all as prelude to what he calls the “Western dominance” that followed. Despite its political incorrectness, Rise presents more than two millennia of non-Western history as the foundation of the West’s rise.

McNeill writes history the correct way, in which truth is allowed to offend insecure tribes, entrenched interests, and implacable ideologues. To cheers and jeers, he summarized the West’s increasingly global presence: “Indeed, world history since 1500 may be thought of as…the West’s growing power to molest the rest of the world.” While honest observers admit the costs of Western expansion, West-o-phobes see all Western expansion as pernicious imperialism. McNeill squares the circle with historical evidence and logical explanations.

His dispassionate take on the barbarism of history provides perspective to those of us witnessing contemporary destruction. “For all their violence and rapine, fundamentally the barbarians sought not to destroy but to enjoy the sweets of civilization,” he wrote. Sounds comforting, even if it doesn’t quite jibe with the catastrophic demands coming from Portland, Seattle, and the Democrats. Maybe yesterday’s hooligans came from a more cultured caste.

Compare last April’s ventilator shortage in New York with McNeill’s summary of ancient Greek cities whose reliance on food imports proved disastrous. “A brief interruption of supply lines could produce severe local famine,” he wrote. And, in third century Sparta where “the few tended to become richer, the rest poorer” McNeill wrote that “revolutionary demands, for the abolition of debts…were frequently heard.” It reminds one of the calls by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and others for free college tuition as recompense for income inequality.

At the University of Chicago, McNeill oversaw the dissertation of my Ph.D. advisor, Walter McDougall, making him my “doctoral grandfather.” McDougall always spoke reverentially of McNeill. Unsurprisingly, the book’s prophetic final prediction floored me: “Intimate and decisive confrontation between Chinese and Western civilizations…promises to generate the most important cultural interaction of…the twenty-first century.”

—John Greenville

Once upon a time I mentioned William Alexander Percy’s Lanterns on the Levee (1941) in a history seminar. The professor rolled his eyes: not that damned moonlight and magnolia again! A fellow student leaped to Percy’s rescue: Lanterns was a serious, thoughtful memoir for serious, thoughtful people.

It is. And it is a portrait of a certain kind of Southerner in a time that preceded today’s culture of accusatory righteousness. It is a book about the South; but also one about Western civilization, back when that term meant something.

Percy, a poet, planter, and all-purpose gentleman, was sprung from a line of Mississippians whose most distinguished member up to that time was his father, U.S. Sen. LeRoy Percy. LeRoy represented a type that no longer exists: a Sartoris, in Faulknerian terms; a foe of the Ku Klux Klan and race-baiting politicians. But by far the best-known member of this family is the great writer Walker Percy, whom Will partly reared following the deaths of Walker’s parents.

The story of the Percys has an elegiac quality, and not only because of the Civil War and its terrible aftermath. There was a stateliness, gravity, and sense of duty that magnified the family and its reputation before and after Appomattox. Will wasn’t one for government-instigated reforms. “All we need anywhere in any age is character: from that everything follows,” he wrote in Lanterns. “Leveling down’s the fashion now, but I remember the bright spires—they caught the light first and held it longest.”

Percy’s view of race relations was open-eyed and without rancor. He felt that conscientious white Southerners had to shoulder the responsibility for freed slaves. “To live among a people whom, because of their needs, one must in common decency protect and defend is a sore burden,” he wrote. The leaders of Black Lives Matter wouldn’t have the least idea what he was talking about back in 1941. They’d probably have smeared his house with graffiti.

Percy was befriended by members of the American cultural elite, who recognized in him a fellow defender of the same civilizational heritage. One gathers from his writing that tyrants in 1941 were still oppressing their own people. He knew nonetheless that “Honor and honesty, compassion and truth are good even if they kill you.” For it was “better for men to die than to call evil good and virtue itself will never die.” Will Percy was Old Roman to his fingertips.

—William Murchison

Leave a Reply