We have arrived at a disruptive, carpe diem moment in our political history. To understand it, it’s worth looking for lessons from a momentous time 160 years ago.

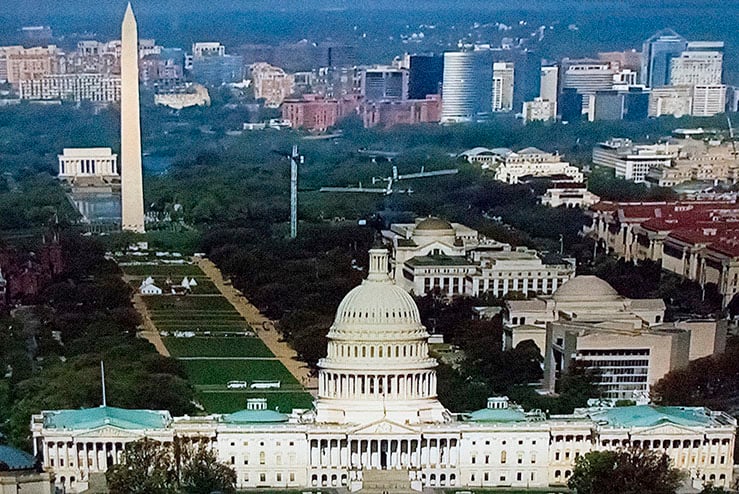

The end of the Civil War’s bloodshed, the abolition of slavery, and the collapse of the Confederate government prompted an imaginative movement to reset the American people’s relationship to the federal government. For the next decade, there was strong support for moving the nation’s capital away from the East Coast to the Midwest—to the “great heart of the Republic,” as one of the idea’s promoters phrased it.

A famous pronouncement attributed to Horace Greeley just after the war’s end was addressed to an individual, but it also signified a big segment of national opinion concerning the central government during the summer of 1865. “Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

Some in the popular movement to make the nation’s capital go West actually proposed to have the White House and Capitol building dismantled stone by stone, packed into railroad box cars, and reassembled in St. Louis. “The fact that many people at the time could imagine that this might really work,” Smithsonian magazine writer Livia Gershon writes, “suggests just how much the nation was in flux following the war.”

In 1867 and 1868, East Coast establishment politicians stopped two proposals to move the capital west from getting out of the House Ways and Means Committee. A third bill to transfer the capital to somewhere in “the Valley of the Mississippi” made it to the House floor and failed, but the strength of support for the measure surprised the establishment. The floor vote was 77 in favor, 97 against.

The movement to relocate the capital persisted.

After the failed congressional votes, Chicago Tribune editor Joseph Medill renewed his efforts in support of moving the capital to St. Louis. “Instead of the Potomac,” he wrote in 1869, “the capital would overlook the Mississippi, so appropriately expressive of the broader tide, the deeper flow, the longer current, and the resistless force our national development has attained…”

This movement had one success in 1874, when Gen. William T. Sherman relocated U.S. Army headquarters to St. Louis. After this, momentum for shifting the capital westward slowed.

Today, a disruptive political environment gives new life to the vision of relocating the national government. The current idea is not to move the entire federal government to one Midwestern city, but instead to disperse its agencies around the country. With Zoom meetings and email, the project is much more feasible today than it was in the 1860s.

Donald Trump has spoken favorably of moving “as many as 100,000 federal employees to “new locations outside the Washington Swamp” to places “filled with patriots who love America,” according to his national security aide Fred Fleitz.

Fleitz writes that most federal employees “can do their jobs more efficiently and economically in more affordable and less congested areas of the country.” He remarks that dispersing federal agencies widely throughout the country would lessen the national government’s vulnerability to decapitation in a military or terrorist strike.

That logic is consistent with a project already taking place. The feds have spent $1.7 billion to base much of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) on a new campus that will open next year in an old and blighted neighborhood on the north side of the city of St. Louis. That is a welcome move for a city that since 1950 has lost more than two-thirds of its population—from 856,000 to an estimated 281,000 today.

Adjacent to the new NGA campus are hundreds more city blocks of mostly crumbling and abandoned real estate that could accommodate other agencies of the intelligence community—and perhaps prompt a change in the culture of the spy agencies and the leak-thirsty media celebrities to whom they cater. Eight hundred miles of cornfields and shuttered factories separate north St. Louis from the Georgetown watering holes—probably an Uber ride too far for the likes of David Petraeus and David Ignatius.

Not only St. Louis but also many other weary, historic places in the heart of America could benefit from becoming new sites for federal agencies.

Fleitz makes a solid argument for moving agencies closer to their constituencies. “For example,” he says, “relocating the Agriculture Department headquarters to a farming state would move the agency closer to the Americans it was created to serve. Agriculture employees could interact with farmers and ranchers on a daily basis. The Agriculture Department could also hire many employees who actually live on farms and ranches.”

Proposals to move much of the executive branch bureaucracy away from the Potomac also anticipate a much-needed reduction in the size of the federal workforce and the scope of the administrative state, including the elimination of entire agencies.

Moving executive branch agencies out of Washington should be just one step in reconnecting the government with the governed.

“It is sometimes hard for people on the coasts to understand the depth of alienation that people in the middle of the country, of all kinds, feel around the notion of ‘Flyover Country,’” Harvard University historian Walter Johnson, a Missouri native, remarked to Smithsonian magazine, “and the way they feel detached from the dominant institutions in society.”

That’s a reason to go beyond ideas for downsizing and dispersing federal executive agencies and workforces. Congress and the judiciary should play their parts too.

Congress already conducts occasional “field hearings” outside the Beltway. Committee hearings and markups outside of Washington should become the norm instead of exceptions. Most staff supporting members in these proceedings could work virtually from Washington, or better yet, from home state and district offices.

Having congressional hearings routinely in state capitals, county council chambers, and other venues far from Washington and its mindset could put federal legislators better in touch with their state counterparts and the people who live in what they are prone to call Flyover Country. At the very least, it warms the heart to think of Adam Schiff, Lindsey Graham, and Elizabeth Warren being forced to spend a couple of weeks every summer in Cheyenne or Jefferson City. The experience might instill in them an unexpected yearning to be term-limited, or even to join Ellen DeGeneres and Eva Longoria on the other side of the Pond.

Holding committee markups in the presence of citizens and local officials far from the D.C. swamp could prove to be mind-opening for both the feds and the locals. Markups, obscure events to most of the public, are where committee members discuss and vote on amendments to legislation before sending bills to the floor, where, in the House at least, debate time is limited, and few amendments are permitted.

Changing the venue for hearings and markups could shift millions of dollars in lobbyists’ spending from Washington hotels and restaurants to the economies of Heartland towns and cities in need of recognition and revival.

Speaking of recognition, one of the keys to Donald Trump’s popularity has been his practice of giving recognition to forgotten Americans by holding rallies in small towns such as Butler, Pennsylvania. Perhaps Congress could raise its public approval rating from the 12 percent to which it plummeted this year if it were to take its proceedings to similar parts of Flyover Country.

Even more easily portable than congressional committee events are Supreme Court hearings. There is every reason for the high court to move about the country hearing oral arguments in county courthouses and historic venues. Supreme Court hearings in the venues of the Dred Scott trial in St. Louis, the Scopes “Monkey Trial” in Tennessee, and Brown v. Board of Education in Kansas would help citizens of all ages connect with the history and significance of the Constitution and the courts.

In the immortal words of Yogi Berra, the gnomic St. Louis native who thought consistently outside the batter’s box and mashed many a metaphor, the nation has come to a fork in the road. Now is a perfect time to take the fork, stick it into the D.C. blob, and tell the swamp hegemony that it’s done.

Leave a Reply