In America today, we seem to face two alternatives: accepting hordes of invaders with alien cultures and ideologies, who are unwilling to assimilate and whose presence endangers the vestiges of our civilization; or homogenizing America into a rootless, soulless melting pot—a “proposition nation” without a past or local or family customs.

Families and learning matter. My father was Col. Egon Roland Tausch (1902-82). He was born to a pioneer Texas-German ranching family, though his father, Friedrich (“Fred”) Tausch, was also the founder and headmaster of the only high school in the county, cofounder of the region’s first bank, and editor of the only newspaper in three counties (published in German and English), and was elected Comal County clerk and then district clerk. Friedrich never had a formal education, there being little opportunity for it in the Texas Hill Country. But he had grown up surrounded by mounds of books and guided by his father, Graf (Count) Friedrich Wilhelm von Tausch, who had been educated at Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, and military schools, before emigrating to the new Republic of Texas in 1844, founding two towns and cofounding one city (New Braunfels, soon the third-largest city in Texas), and fighting Comanches until the negotiation of an early and lasting peace between them and the German settlers.

Though my grandfather Friedrich was of Prussian descent and therefore a “freethinker,” my grandmother Agathe, daughter of a proud Texas Confederate veteran who had lost everything in the War and Reconstruction, was of hardy Bavarian peasant stock and a devout, if “secret,” Roman Catholic. Fred Tausch spoke six languages fluently, including two ancient ones, making use of all of them in his letters to each of their nine children so they would not forget. He also found time to publish two rather dense books in English and German, and became a constitutional scholar and enthusiast for states’ rights and the separation of powers.

Friedrich and his wife lost two sons, Rudolph and Arno, in the trenches of World War I, though that did not deter drunken “Englisch” San Antonians from attacking their large Victorian home in New Braunfels, along with shooting out the streetlights and closing down Tausch’s “German” school.

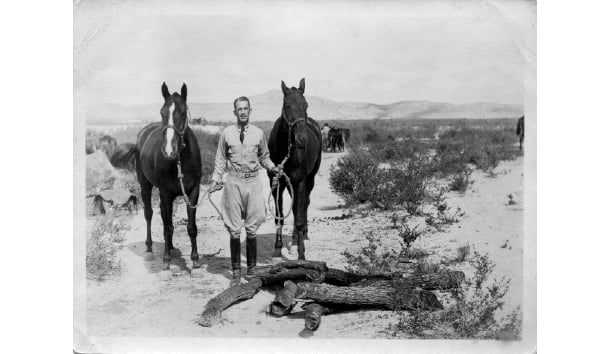

As a kid my father ran skunk traplines for pelts, studied, helped at the presses, hunted, hired out as a cowboy, maintained his marksmanship at the Schuetzenverein (shooting club), practiced the Viennese Waltz at the Turnhalle, and learned the newer ragtime tunes of famed Texan Scott Joplin (who had been mentored in composition by a Texas-German). Of course, for Friedrich’s family to touch all secular vocational bases one of his children had to go to West Point, and that was my father, after a stint in the Texas National Guard. Egon graduated the academy in 1926; his sports were boxing, wrestling, horsemanship, and marksmanship. He joined the horse cavalry and was given a troop patrolling the Texas-Mexican border and protecting it from bandits. (Washington tried to turn the troop into “machine-gun cavalry” until Dad vehemently complained of the resulting slaughter of his men’s own horses during open-fire practices and charges.) He regaled his men in bivouac with Texas-German doggerel-in-dialect he picked up who knows where, one of which ended, “I schmokes de Keptain’s best cigars, I drinks de Keptain’s schtoudt. De Keptain comes de front-door in, I goes de beck-door oudt.” Then he would fake a cockney accent for the old cavalry chant, “Hit’s the ’ammer, ’ammer, ’ammer on the ’ard ’ighways wot ’urts the ’orses ’ooves.” Years later, old men who had served under Dad would recite them to me.

About this time the silent movies Wings and Rough Riders were filmed in San Antonio, and my father’s cavalry troop was sent up to play bit parts and background because their uniforms were similar to those for the two movies. Dad can be seen climbing into a biplane, which he had no idea how to fly. He never forgot dancing through the night with Clara Bow after filming; she eschewed the Hollywood crowd that night. My father celebrated the next night by ripping down the common restaurant and speakeasy signs that read “No Dogs or Soldiers Allowed.”

Captain Tausch was selected to teach and administer at the Spanish Cavalry School in Madrid. Unfortunately, after a year he led a practice cavalry charge over a well-disguised cliff and broke his leg in five places, the only casualty in the maneuver. His long recuperation in various Spanish hospitals not only improved his artistic skills (sketching and etching) but singularly prevented him from galloping off and following his cadets to join Gen. Francisco Franco’s invasion of Andalusia to save Spain from the anarchists and communists.

Dad’s next assignment was as instructor, later professor, of Spanish and German at the USMA at West Point, after a tour at the Command and General Staff College. While at the academy, he became friends with fellow alum Anastasio Somoza, later dictator of Nicaragua, and was assigned to escort high-ranking German officers such as Hermann Göring, despite Dad’s private disgust with the “white-trash” Nazis.

He also saved the life of the child of a West Point faculty member, which child had wandered off a cliff at Storm King Mountain and was trapped on a ledge many feet below. At great personal risk, Dad pulled young Gore Vidal to safety. Years later, when he read Vidal’s homosexualist books, he told me, “I should have let the little bastard fall.”

On his way to West Point, during a tourist steamboat ride up the Hudson River, Dad met and fell in love with a lovely San Antonio debutante and homecoming queen who had earned one of the first M.A.’s given a woman at the University of Texas. Frances Lawrence Briggs was similarly multilingual (with a Southern accent). Thanks to his leg cast and her scintillating conversation, they sat out every dance and were engaged by the time they arrived at West Point. They wed at the Cadet Chapel, to the disgust of her parents who, though also “Texians” and Confederate (and fellow atheists), disapproved of all Germans and their descendants. Her father, an oilman and newspaper editor, had been an artillery officer in the Great War, and would not believe that the Texas-Germans fought in the trenches to his front.

The young couple’s next assignment was at Monterey, California. Horse-cavalry officers formed a small, elite club at that time, and were encouraged to compete at civilian horse-mastership sports. Dad excelled and won silver loving cups at polo, steeplechase, lancing, racing, “watermelon-slashing,” etc., including the coveted Pierre Lorillard Award, as chronicled in the San Francisco newspapers.

His growing fame in certain circles, for his skill and for his slight “continental” accent, cultural knowledge, elegant charm and wit, and reputation as both a bon vivant and a patriot, led FDR to pick him for the Foreign Service. The Foreign Service of the time was forerunner to the OSS, CIC, and CIA. Dad rose to colonel as military attaché to Mexico, where he discovered Leon Trotsky’s murder and, later, in a secret raid on the Japanese embassy, plans for their two-man subs suspiciously surrounding Pearl Harbor (discoveries squelched by the White House). My sister was born in Mexico City, on Cinco de Mayo, with full black hair, black eyes, and olive skin, to a blonde, blue-eyed mother and a green-eyed Aryan father, causing a rumor, short-lived for safety’s sake.

FDR had launched his “Inter-American security and cooperation” offensive (against fascism), drafting Disney’s “José Carioca,” Carmen Miranda, and every calypso band around, and Dad served variously as military attaché among Mexico, Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), Cuba (where he punched out a drunk and abusive Ernest Hemingway at the embassy), Uruguay, and Argentina. To counter his bête noire (the fashionable “citizen of the world”), my father managed to convince each embassy to celebrate Texas Independence Day with a formal reception for all Texans in the country, in front of a huge, silk state flag. After we entered the war, Dad vainly demanded combat command in the Pacific or European Theater, where his brother Norman fought under Patton. (I was born on the Atlantic and reared largely by my black Cuban Mammy.) My father had to settle for being instrumental in the capture and sinking of the Graf Spee, for which he was decorated, despite our “neutrality” at the time, and helping to orchestrate the first major defeat of Juan Perón of Argentina. Perón had gathered the reins of power in his country, though he wasn’t actually elected dictator until after the war. But like much of the Latin American military, he was a left-wing fascist for reasons too complex to go into here, though they explain the continent’s tolerance for and often welcoming of (at least for a while) military coups. Perón was threatening to supply the Axis Powers with Argentina’s vast beef, wheat, and other agricultural resources. After his wings were clipped, Perón invited Dad to his farewell party as his “greatest, most trusted friend.” Our home is covered with formal, bemedalled portraits of Trujillo, Batista, Perón—inscribed to their “best friend,” todo un General, when they were members of his handgun-sports “Dictators’ Club.” Dad later warned Washington about a young Cuban student in Mexico, a communist, named Fidel Castro. Throughout Dad’s Foreign Service career, he was dogged by journalists and photographers.

Mother was the perfect diplomatic consort and wrote and published Spanish-language novels and travel books on the side. I spent most of my time at our embassy-issued estate on the pampas, with our gauchos.

When we went to Washington, my father became chief of the Military District of Washington and cofounder of the CIC, later the CIA. During the Korean War, he was G-2 (Intelligence) and “listener” to the North Korean screamer at the “peace talks” and POW exchange at Panmunjom, though he did get decorated for some combat and was shot in the finger. When he was up for general, he was short-stopped in Congress for still-unknown reasons by Clare Boothe Luce, U.S. representative, ambassador, and wife of the publisher of Time. Dad was informed that he must become a Christian, so he ordered the priest at the nearest historic Episcopal church to baptize, confirm, and appoint him rector’s warden within two weeks, at age 50. The priest agreed, and it was done, but when Dad failed to make general afterward, he gently forbade us to return to church.

I, of course, was busy learning English, having spoken only Spanish and German at home and at school. We weren’t burdened with “bilingual” education for English; it was always total immersion, even at home. Dad began and punctuated my instruction with Rudyard Kipling’s “If,” Dad’s personal, pocket “bible.” In spite of the certainties of his contemporary “intellectuals,” my father knew that Kipling was no imperialist, respected the poet’s “Gods of the Copybook Headings,” and feared their revenge against modernism. Because of my Spanish accent, my maternal grandmother promoted me from “The Hun” to “The Spic” or “Wetback” during our many trips back to Texas. That never bothered me. (I later learned that my father had supported his formerly rich in-laws during the Depression.)

Meanwhile, in 1950’s Washington, I had to put up with Dad’s explosions over the Washington Post, Drew Pearson, Herblock, Yankee politicians, bureaucrats, and the Kennedys, our next-door neighbors in Georgetown. I became one of the much-photographed “street urchins” the Kennedys brought along for cover when they visited mistresses in the Shenandoah Valley—until Dad read of it.

My father always refused to vote, as did a lot of Army officers of his time, because he agreed with Frédéric Bastiat that he had a dishonorable conflict of interest, since he could vote in favor of a raise for himself out of the federal treasury.

We toured all the Virginia and Maryland battlefields, where Dad pointed out the Confederate positions and outlined the action, so I could return and do so on my own. He talked of each Confederate hero as though he knew him personally—especially Jeb Stuart’s Maj. Heros von Borcke, a Prussian. We went to visit a Civil War cemetery, only to find it freshly denuded of all its gravestones. Within a few months he found the stones paving a congressman’s garden in Georgetown. Father reported it with a signed affidavit, and soon the stones were replaced in the cemetery. (Perhaps that was why he never made general. I still have no idea what became of the congressman.)

Dad got his nephew into West Point and an Army career, I suspect as a backup for me, should I fail. Being a draftsman and an amateur architect, Dad found time to restore and gentrify whole blocks of colonial houses.

Along the way my father attended and taught at the Army War College, was awarded the Legion of Merit—the nation’s highest noncombat medal—twice, earned two master’s degrees and one Ph.D. (ancient and modern history, and Spanish, English, and European literature), taught at American University, and wrote several geopolitical books and one scholarly history of Poland (though he was never there).

During my mother’s “Socialist Period” in Washington, I was enrolled in a D.C. public school. Had this been in today’s California, I would likely have gone to prison for the glorious pictures I drew of my armed soldier-father. As it was, after a year or more of paying my lunch money for passage through the gangs but still returning home bloody with knife wounds (which I hid from my father), and being taught absolutely nothing in school, I ran away from home at 14, leaving a note that I would be sent to Texas Military Institute (a San Antonio boarding and prep school), or my parents “would never see me again.” Although the school almost bankrupted my family, I justified it on the grounds that my chosen college (West Point) would be free. However, I later decided to go for a year to the University of Texas first, working my own way. Dad and TMI had given me enough education that I breezed through two years of the university in one, while holding down my jobs, and decided to remain there through my first M.A., working the ranch on weekends and during the summer.

My father retired again after serving as chief of the Texas Migrant Labor Council (the “Bracero” program), winning the respect of the far-left, right, and agricultural interests. Dad then worked full-time at the ranch, raising purebred, registered Herefords, restoring and expanding our limestone 1849 ranch house, and studying the Roman Republic. A huge mama sow bit off my beautiful mother’s right arm while she was trying to untangle a piglet from barbed wire, and Mother died not long thereafter. Dad never fully recovered. Impulsively, he shot each pig with his Army .45 but was heard to remark later, “I wish I’d loaded them on the trucks first.” By that time, I was stationed in Germany, then Vietnam. My sister, Frances Clementine, moved to California with Janis Joplin and the 13th Floor Elevators, both singing with and managing the band. She eventually settled down as a conservative legal secretary.

How did Dad and I get along? I worshiped him and, at times, hated him. We were always in competition. When I took up a hobby—making bows and arrows, carving, horticulture, entomology, mineralogy—he would “help” me, taking over until he was an expert and I’d lost interest. No need to discuss Dad’s effect on dates I brought home. Dad could not apologize after a nasty argument; a few days after one of them, his victim would find a beautiful gift at his door or stoop. I had the solemn duty of trimming Dad’s brown toe-claws with a hacksaw, the result of generations of horses stomping on them. My father never raised his hand to me; a raised eyebrow was sufficient. Though he would never have told me, I learned years later that the week I was MIA in Vietnam, presumed killed (a clerical error after the Battle of Ðak Tô), my father became an absolute, bitter hermit, until my survival was shouted to him from the road. Then he recovered his nonchalance.

Two years before he died, Dad sincerely converted to Christianity. Having preceded him to the Faith, I pray his mental conversion was partly the result of our seemingly endless historical and theological arguments and debates. The night Dad stopped lecturing and started asking questions was one of the best in my life. Those who say that “No one was ever converted by a syllogism” never met my family. Several syllogisms might have brought generations of my family to within hearing distance of Christ’s knock on the door, as was done for me. My father did, however, have great difficulty composing his first Confession.

Dad died happy, after singing to his extended family for over an hour, in his once rich, now cracking, baritone. Mexican, French, and German folk songs, with Stephen Foster and “The Yellow Rose of Texas” (original version) interspersed. Not a word was lost, or mispronounced. I was surprised that so few in the room joined in; having grown up around Dad’s singing, I forgot that modern Americans will not sing spontaneously in public. My father had to die young, at 80, since he had smoked from the age of 16, mostly unfiltered Chesterfields.

My father was a man’s man, a woman’s man, and a son’s exasperation. My wife accuses me of still competing with him, but I might be catching up in my old age since I smoke filtered Marlboros. Of course, I spent ten years mostly overseas as an officer in the Regular Army (infantry, there being no cavalry) and became a linguist, oil artist, singer, writer, and academician (including West Point) in history and literature. I did some spying in Panama and Mexico during crises there in the late 1970’s, for private concerns, though I testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (which ignored my reports). Dad was ambiguous about my eventually becoming a lawyer—it wasn’t on the program. But I did take over the beloved hills of his ranch.

Dad’s virtues, throughout his life? Duty, honor, country (and family, Texas, the South, roots, courage, loyalty, self-discipline, intellectual thirst, good taste, urbane wit—and marksmanship). His sins? Too many to count, but primarily, like most human sins, dangerous excesses of virtues.

Why did I write all this? Damned if I know.

Perhaps it is because my father’s virtues now seem to be in short supply, and I know that it is possible for those so inclined to assimilate—to be a patriotic American—without losing those virtues, the threads that compose the fabric of a life well lived.

Or maybe it’s his oil portrait staring at me as I go upstairs, painted by Juan José Segura, the best pupil of Diego Rivera. (The portraits of my father and mother are the only pictures Segura did without a hidden hammer and sickle, according to his biographer. Though he did put Dad’s disastrous charge in Spain in the background, as irony.) My father is dressed in his formal, mess blue uniform, cavalry-yellow satin lapels, gold epaulets and fourragère, with his strikingly handsome face, and his clipped military mustache bristling at me. I think I now detect a twinkle in his eye.

Leave a Reply