Leon Redbone left the scene in 2015—I don’t mean that he expired, but simply that he retired. There was mention at the time of health concerns, but he was through with television appearances and concerts and touring, and with recording as well. There has been almost nothing about him on the national scene since then, but there has also been a certain presence even in an absence. Leon Redbone was such a phenomenon that his image, as distinct from his personal individuality, cannot be forgotten.

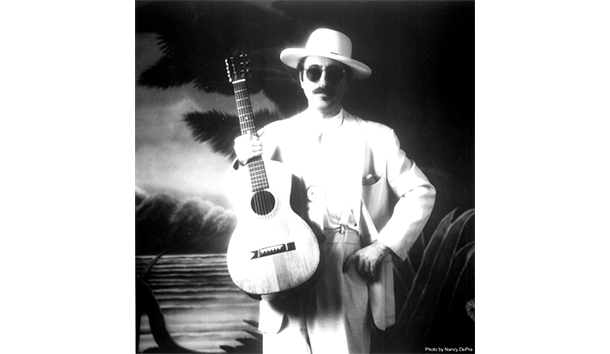

Leon Redbone was—and forever is—a singer and acoustic guitarist who came across as the ultimate hipster, what with his sunglasses, his Panama hat, his black tie, and his assured and even sly presence. Somehow, his look and his skills and his repertory were all fused into a singular experience. When his success is set against his singularity, we begin to see how particular and focused it all was. And perhaps we also realize how much we owe to him, in terms of the musical service he embodied. There was so much contained in the performing individual that it was hard to take in all at once.

But before we address what he performed, we must note how he performed it. Though he was often accompanied by a clarinetist or a trumpeter, he was also quite effective all by himself. His guitar-playing was altogether acoustic in its sound and assumptions, and this was fundamental. His singing was highly idiosyncratic but no less effective for that. I will have more things to say about Leon Redbone’s singing. Let me first say, however, that the direct encounter with the experience of his musicianship is easily and extensively available on YouTube.

But getting past the elements of the performance package, the most obvious and weighty effect of the Redbone phenomenon was his repertory—his selection of material, the songs he sang. He seemed to restrict himself to the 40 years before World War II. In other words, he was a retro-oriented musician. His fascination and obsession with disappeared or even cast-off popular music was eminently respectable, but it was also against the grain of historicist presumption. It was against the economics and the corporate doctrines of the 20th century. It represented the aesthetic of the music buff rather than that of any performer whose object was survival, not revival. And yet he made it work. He had success in reviving repudiated music just where you would expect him to fail, or at least to come up short.

Beginning in 1975, Leon Redbone was often seen on Saturday Night Live, not exactly a source for the retrospective view or audition. He was also a frequent guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, which was no refuge for the music of long ago—just ask Doc Severinsen. The appeal of Leon Redbone was not generational, nor was it merely nostalgic. But that appeal was powerful, and it was felt, not only by colleagues and proponents of the new culture that had repudiated the old one, but also even across the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans.

As a performer, Redbone was a balanced presentation—the sounds he produced were related to the material he covered. His sources went back to the turn of the previous century, even to the days of ragtime, and then to early blues and jazz and some music from Tin Pan Alley. There was a claim that when he played, you could hear the swish and clicks of the old 78 rpm shellac discs. The material he presented had its own sound, and Leon Redbone was faithful to that sound. He even went so far as to denounce the deterioration of the sound of contemporary music itself: “It’s just noise volume level, with no sentimentality at all.”

As for the sounds he made himself, they were acoustically resonant, both from his guitar and from his chest and head. He was not averse even to yodeling or to other playful engagements with sound production. He did not have an “edge”—he did not escalate the dynamics and blare at the audience. Instead, he pulled the audience to him with his flamboyant relaxation. If lowering your voice is a way to pull the audience in, so were Leon Redbone’s seemingly relaxed resonances.

There really wasn’t anyone to compare with Leon Redbone, though perhaps some folksingers or country-and-western singers might be suggested. But one of the most remarkable things about him was his mysterious past. He seems to have been born in Cyprus, which would mean that he did even more than reverse the codes of contemporary popular music: He did it across a linguistic and cultural barrier even harder to bridge than the evolution of American popular music. And if indeed he did accomplish that much, then his musical gift alone, like that of some others, trumped the difficulties that he dealt with.

As for his repertory, I think that it was our repertory—the one that had been let go, forgotten, repudiated, laughed at, cast aside, and blown away. There comes a point when old popular music becomes problematical, or even the property of Lawrence Welk. Leon Redbone was something else—he was not so much reviving old songs as he was recreating them in a more than persuasive manner.

Bob Dylan was but one who respected Redbone. Perhaps he saw or heard in Redbone something of his younger self, or even of his better self. But however that may be or have been, a look at some of this repertory is almost shocking in its familiarity—and in its naiveté and “sentimentality,” as Leon Redbone idiosyncratically put it. Such a view would lead us directly to question the basis of his presentation. Was he putting us on? Was he a parasitic mocker of what had already been sneered at? Should we classify him with, say, Tiny Tim?

“Tiny Tim,” or Herbert Khaury, was a camp figure who sang old songs in falsetto and imitated old recordings, but there was no camp aspect in Leon Redbone’s presence on stage. His presentation was straight. Johnny Carson was obviously cruel in his patronizing exploitation of Tiny Tim—but such was never true about his promotion of Leon Redbone.

The matter of specific repertory is perhaps less revealing than it would seem to be. The point is not the songs themselves, really, but their renewed persuasiveness as performed with unique flair by an uncannily effective proponent of them. I am thinking, or rather remembering, Redbone’s resuscitations of tunes like “Up a Lazy River,” and all the other ones. I sense that there was something particularly special in “Your Feet’s Too Big” as well as in “Ain’t Misbehavin’”—Fats Waller recorded both, though he himself wrote only the latter. The comic spirit of Fats Waller says much about the revivalist spirit of Leon Redbone, for there was nothing sanctimonious or self-aggrandizing in his recreations. Redbone was demonstrating that some sentiments required enough latitude that they could breathe—or, as Fats Waller put it, “One never knows, do one?”

“Shine On, Harvest Moon,” “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” “Polly Wolly Doodle,” “The Sheik of Araby,” “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone,” “Marie,” “Sweet Sue, Just You,” “I’ll See You In My Dreams,” “My Blue Heaven,” “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” and “Moonlight Bay”—all of these are among Redbone’s revivals, but they raise questions or wonderment even beyond his performances. Why is it that we know those songs? They were already in our collective heads before Redbone did anything about them. They are part of our cultural patrimony. (I can’t say “matrimony,” now can I?) They are part of the “sentimentality,” as Redbone named it, which exists in the hazy envelope containing them. Redbone refreshed our acquaintance with what we already knew—and he brought us to it with a unique but appropriate sound. The music was already there, as were the lyrics—but not the sound.

Was or is Leon Redbone actually of Turkish descent, originally named Dickran Gobalian in Cyprus, as has been claimed? I don’t know the answer to my own question, but someone other than Leon Redbone probably does know that answer. In the meanwhile, we have to contemplate the possibility that the successful revival of American music by an immigrant is a matter not so much of cultural synthesis, but of penetrating musical intuition.

So the 40 years of his performances are represented today by the many albums he recorded and by his appearances before the cameras. It is all there to be enjoyed, and more than appreciated. If his music-making pleases, then it is its own reward—even more than that, justification. Going beyond the immediate experience of the charming and impressive presentation of appealing songs that we know from Leon Redbone is the larger question of history and culture. The question is not “Baby, Baby, Where Did Our Love Go?” so much as it is “Where Did Our Music Go?” and “Why Did It Have To?”

As the word implies, a “revival” means that something once had life, and now does again. If Leon Redbone was successful in his revival of old tunes, it’s because he had the savoir faire to pull it off. But what about the rest of us, who depend on musicians and the music business for the satisfaction that musical art provides? Having in effect been deprived or otherwise ripped off, we are quite possibly in the position of needing to recreate if not create good music for ourselves—or to discover another Leon Redbone.

Leave a Reply