How could I possibly know as much as I do about popular entertainment? I mean, I almost never go to the movies anymore. The big multiplexes annoy me with the stink of their sprays, their even more vexing segmentation of the audience, and their usurious popcorn prices. At home, I have no time for television, being completely devoted to religious meditation, arcane studies, and my hobby, organic chemistry. But let’s face it, the worst thing about movies and television today is what you see. “Entertainment” palls when there is so little pleasure to be found. And the imagination is not stimulated by an awareness of the manipulations of the entertainment industry.

One of the creepier experiences of actually seeing what is going on, though, is the realization that the presentation of humanity itself is more than a bit lacking. “Men,” for example, seem to be beer-swilling louts who wear Hawaiian shirts. “Women” appear to be anorexic teenage models who are exploring their sexuality. Where is some norm of reference or ground of actuality? Maybe the point is that there is none.

Looking at the whole male/female situation now makes you wonder. All the little chippies that the powers put in front of us at the multiplex and on the cable leave me cold, perhaps because I do not want to look at any navel display unless I am the only one who gets to see it. Over 30 years of sexual revolution, radical feminism, ethnic truculence, homosexual agitprop, and all the rest of it have resulted in the present confusion, a situation in which von cannot even expect to see a good movie. There are a lot of reasons why that is so, and there are exceptions, and there is as well the distorting complexity of reading the dialectic of history through illusory commercial artworks that are themselves both the cause and the result of what are now called “changing gender roles.” The “gender blender” is why, in movies today, we so often see males hugging and crying and saving things like, “I love you, man.”

I can remember when a “weepie” was a woman’s movie, a handkerchief thek. And by the wav, some of the old women’s movies were so good that anyone could enjoy them, and did. Today, a woman’s movie is something like Thelma & Louise (1991), which would have been a lot better in black and white, made in the early 50’s, with maybe Dan Duryea and Stephen MacNally instead of Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis, and the rape stuff by the evil men left out. So Callie Khouri won an Oscar for the lousy screenplay. Go figure.

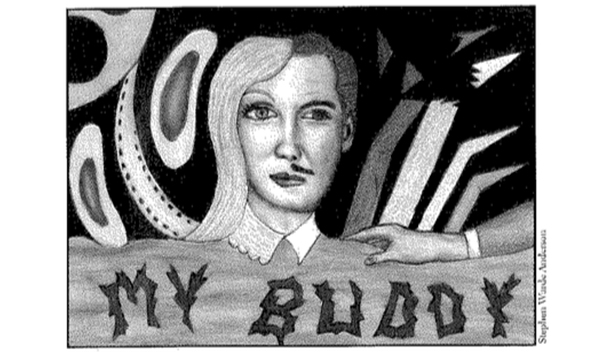

As a chick thek, Thelma & Louise was a road movie, and it was a buddy movie. There was a niche, at least, for the conception. But still, it was a feminized, possibly lesbian version, complete with Liebestodt, of a sinister male phenomenon, and I mean the buddy movie, not the road movie or the usual crime story.

The buddy movie is a problem, and a revealing one. I do not want to blame everything, or even anything, on Neil Simon, who wrote The Odd Couple. That comedy had its own point. But the ceaseless replication has contained a subliminal message. I think that there have been so many buddy movies because, after the sexual revolution and the collapse of convention in the 60’s, the usual sentimental melodrama of love and recognition of the other self could hardly be told in terms of male and female, and for two reasons. One is that the story of male and female entanglement has essentially required from unimaginative moviemakers and audiences a pornographic representation, complete with female orgasm. Love cannot be represented without graphic display of same. Therefore, the difference and recognition between individuals could only be desexualized through the buddy movie. And this leads to the other reason for the buddy movie: the feminization of the male, and the subcontextual establishment of homosexual relations as a norm, rather than a mere perverse possibility, of romance.

So let’s talk about Oscar and Felix, since everyone remembers them. Oscar was the slob, with his beer and pizzas and ball games and rough ways and gruff talk. Felix was different—sensitive, artistic, neurotically whimsical, obsessed with the finer points of housekeeping. It is not a point of rocket science to suggest that their amusing conthet was a transmutation of the male and female principles. Supplied with various girlfriends, not to mention ex-wives, Oscar and Felix were carefully protected from the implication of the tensions between them. But that tension was there, as it had formerly been between Ralph Kramden and Alice, and between Ricky and Lucy. May I point out that these heterosexual pairs were married? It is a point of law today, as well as a point of church doctrine in some places, that Oscar and Felix could make it legal and sanctioned. They might as well have done so, there being no doubt as to the identity, respectively, of groom and bride.

Ain’t love grand? Certainly, we can continue, in this delightful as well as instructive vein, to explore some of the variations of the buddy movie. Planes, Trains, and Automobiles (1987), written, directed, and produced by John Hughes, was a thin movie perhaps, but effective and amusing in its own way. The odd couple this time are Neil (Steve Martin as the fussy Felix type) and Del (John Candy as the vulgar Oscar type). Stuck together on their accidental odyssey, their opposition is reconciled at the end by the sanction of one wife and the memory of another, but the movie itself presents them almost always together, even in a bed they are forced to share. They awake in an embarrassing embrace, which they shake off by asserting their masculinity in nervous and silly talk about football, but a more transparent example of what today is called “homosexual panic” cannot be imagined. Such an allegorical scene, though funny, would appear to be driven by a need to assert didactically that our sexual identity is “socially constructed ” and, therefore, easily deconstructed and reconstructed as well. The final scene with the smarmily smiling wife would seem to give female approval to a husband’s newly loved boyfriend. It says, “We understand.” Indeed, we do.

Midnight Run (1988) is again a comic road movie as well as a buddy movie, but it is a more ambitious melodrama featuring the Mob, the cops, and guns. The bounty-hunting Jack (Robert De Niro as a contheted Oscar) takes Jonathan (Charles Grodin as a Felix) across the country, and they spend much time handcuffed to each other. The rough, gruff Jack finds that he needs the emotionally insightful and supportive Jonathan to work out his problems with his life as an ex-cop and ex-husband. There is a happy ending, but my question is, how could this odd couple bear to part from each other? The answer would seem to be, with great difficulty.

The dim-witted brothers in A Night at the Roxbury (1998) sleep in the same room, though in separate beds. After they are confused by two prostitutes and one sexually aggressive husband-hunter, they wind up back together, those difficult and sexually demanding women repudiated, as though to suggest that incest adds spice to the usual homosexual bliss. I must add that A Night at the Roxbury is funny, and we could go on and on about buddy movies, as for example with Robert De Niro (as Oscar again) and Billy Crystal (the name of the type begins with “F”) in Analyze This, and with too many others, but I think I have made my point. The metastasis of the buddy movie is a substitute for the old battle of the sexes, courtship, cathexis, etc., a substitute for the representation of graphic sex, and subliminal propaganda for the homosexual worldview as well. This hypertrophy is an oblique but decisive step in the feminization of the male as represented in popular entertainment, a result of feminist/homosexual ideology, and a cause of the continued breakdown of the male ego, particularly as that delicate construction is reflected in die teenage mind, the target audience for such films. Or should we rather say that the new Hollywood has given us a more diverse, inclusive vision, breaking down old stereotypes and gender roles? Like Mike Myers playing Linda Richman, I get all verklempt just thinking about it.

Feminization is a powerful and pervasive force, and not merely an abstract topic of analysis and speculation. Feminization is the explicit topic of melodrama itself—it is what the audience expects to hear addressed. Is there anything else to talk about? Strangely enough, it has manifested itself even in Clint Eastwood movies. In Sudden Impact, Dirty Harry was disgusted that Tyne Daly was his new partner, in a dramatization of feminist quota blather. But in Heartbreak Ridge, the tough sergeant was reading women’s magazines, trying to get in touch with his feminine side and figure out Marsha Mason. In Tightrope, Clint’s character was attracted by the perversities that were the kinky mark of the killer he traced. Was Clint getting in touch with his feelings, exploring his sexuality, or trying to tap the female market? And what is the difference anyway?

But wait a minute. Feminization is not enough. The further degradation on the way to dehumanization is not feminization but infantilism, and that has been the obsession of other and more brilliant comedies than the buddy movies I have cited. Dumb and Dumber (1994), starring Jim Carrey and Jeff Daniels, is a road movie about a pair of moronic losers and roommates, but they are not modeled on Oscar and Felix: Neither of them has that high an intelligence quotient. Mindlessly girl crazy, the dummies in their misadventures cause giggles about every phenomenon of the nursery, toilet training, the indiscipline of the body: There are scenes of playing with food, two routines about urine, one about phlegm, a gross-out scene about induced diarrhea, and so on. The scatology is mixed with heterosexual fantasies which must remain just that for these overgrown babies who lack only diapers and a nanny. This funny movie is nightmarish in its implications—the laughter it provokes must hide more than a little embarrassment, at least some of which might reflect rather than repress the thought that Dumb and Dumber is essentially a feminist/lesbian, not a satiric, treatment of masculinity; Men are just babies, after all.

The political implications of moronism should be borne in mind also when viewing the masterpiece (at least so far) of the Coen brothers, Joel and Ethan. The Big Lebowski (1998) is an absurdist treatment of contemporary Los Angeles lowlife as well as a wicked parody of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely, or at least of the films noirs made from those novels. This point is valuable, for it gives us a measure from the 40’s to the 90’s of the disintegration of masculinity itself. Chandler’s detective hero, Philip Marlowe, combined qualifies of integrity and intelligence with strength and honor. His chivalry may have been unavailing, but it was there. Jeff Lebowski, as portrayed by Jeff Bridges, is smart at least twice, when he is not bamboozled by all the milk cocktails he puts away, but that is not often. Sucking on drugged milk, mumbling inanities about the 60’s, putting his hair up with a pin, lolling on his back instead of sitting up straight, serving as a sperm bank for a pushy feminist, lying in his tub, losing every physical encounter he has with anyone, unemployed and unemployable, this whiny bowling bum is only one hilarious character in a movie full of them. But most important for our purposes, he is no kind of a man. He is literally a baby, perhaps the most passive and put-upon schlemiel in the history of film.

I do not think that the Coen brothers meant to advocate any political position when they created Jeff Lebowski—they have instead brilliantly satirized a figure who represents what has already happened in a certain subculture of L.A. Chandler’s hero of modest proportions has become the hapless victim of the slightest force—passivity can go no further than the pathetic as well as ridiculous weakness and narcissism of the little Lebowski. As the narrator says in introducing the film and parodying Chandler himself, “Sometimes there’s a man . . . The man for his time and place, he fits right in there.” We can add that Jeff Lebowski is a member of a trio of losers, a male menage that has become a twosome, an odd couple, by the end. They wind up hugging and returning to their bowling alley. But having claimed so much for this superbly crafted movie, I have to say also that “the f-word” is used in it more often than in any other film: an average, I think literally, of more than two and a half times a minute. You have been warned.

What does it all mean? Well, let’s see. I remember when a professor asked me only half ironically, “What is our place in the world-historical process?” If we could figure out that one, then we might coherently answer. So here is one way of putting it: We live in a world that, instead of projecting a Humphrey Bogart (as not so long ago it did), now lives by the image of Woody Allen whining about not being as heroic and romantic and strong as Humphrey Bogart.

Let’s put it another way: Feminism should be seen as a symptom and not a cause of modern decadence, endorsed by men because of lust. The destruction of masculinity is an essentially post-industrial requirement, sponsored by government and justified by science as well as ideology. Playing their part in the destruction, and making a lot of money, movies help in urging the process along. The consumers—that is to say, ourselves—have been complicit in self-destruction, and have cooperated with it, even helping pay for it. The agenda of “change” was identified by Mary Shelley and Nathaniel Hawthorne, among others, a long time ago. Seizure of control of life itself, and of its creation and destruction, is part of a Faustian agenda that has been agreed to again and again by the denizens of democracy. The Gothic tradition, as known to us through the horror movie and the science-fiction flick, speaks to us most powerfully as to the implications of our politics. With her knowing smile, Sigourney Weaver in Alien Resurrection has managed to imply both that lesbianism is a Gnostic privilege and that we must become the alien Other.

Watching comedies that are horrible and horror movies that are morally, not only graphically, grotesque, we may perhaps reflect upon the progressive agenda that permeates the Zeitgeist: feminization, infantilism, dehumanization. Classics like the original The Thing and Invasion of the Body Snatchers showed ordinary human love as the last defense against the very dehumanization which is now the ineffable and inevitable goal of the elite who define “popular culture.” That’s entertainment. Is everybody happy?

Leave a Reply