The 46-year-old veteran frontiersman lay in bed, desperately ill. He was suffering from the effects of a gunshot wound that he had received in a fight. But duty called. The state legislature asked him if he would lead an army of volunteers to engage the rampaging Red Stick Creeks. Though scarcely able to sit up in bed, he said that he would have the army on the march in nine days. True to his word but looking skeletal and decrepit, he had the volunteers on the road by the promised date. He moved them toward the enemy stronghold at the rate of 20 miles a day. The troops thought surely the Old Man would weaken and die. Instead, he gained strength day by day, his fierce visage and blue eyes burning with an unearthly intensity. He was a commander who inspired his men. He had an iron will and a lean sinewy body to go with it. He did not get his nickname for nothing. Old Hickory was all grit and fight.

The Red Stick faction of Creeks, who were armed by, and allies of, the British in the War of 1812, were about to suffer the wrath of Andrew Jackson and 2,000 Tennessee frontiersmen. In the first engagement of the two forces, a detachment of Jackson’s boys killed more than 200 Red Stick warriors. “We shot them like dogs,” said a tall, lanky frontiersman in the detachment. The frontiersman was David Crockett. Jackson’s force caught up with the main body of Red Sticks a couple of days later. More than a thousand Indian warriors came rushing out of the woods at the Tennessee boys “like a cloud of Egyptian locusts,” said Crockett, “and screaming like all the young devils had been turned loose, with the old devil of all at their head.” Crockett and his comrades coolly marked their targets, took careful aim, and began firing. Each shot had to count—reloading took 30 seconds. Their firing was disciplined, accurate, and deadly. The fight took no more than 15 minutes. By then, the ground was littered with the bodies of more than 350 Red Sticks and those warriors who had survived the carnage were fleeing pell-mell through the woods.

The final battle occurred at Horseshoe Bend, where the Tallapoosa River loops around a peninsula. The Red Sticks had built a log barricade across the base of the peninsula and figured that Jackson’s troops would either have to swim the river, exposed and vulnerable, or come over the barricade, equally exposed and vulnerable, to get at them. Jackson surprised the Red Sticks by doing both. He had some Indian allies swim the river and attack the Red Sticks from the rear while he sent his Tennessee boys in a frontal assault against the barricade. The Red Sticks were shocked by the mad rush of frontiersmen at their stout barrier. Through heavy fire, the Tennesseans came, clawing their way up and over the logs, and into the midst of the Red Sticks, fighting hand to hand. This time the Indians could not retreat by sprinting into the woods, although some tried to escape by diving into the river. Shooting, clubbing, and stabbing their way through the Red Sticks, the frontiersmen turned the fight into a rout. By the end of the battle, nearly 600 Red Stick warriors lay dead on the peninsula, and another 300 Red Stick corpses were floating in the river. Jackson thought that not more than 20 warriors had escaped. For all intents and purposes, the Red Sticks ceased to exist. Jackson had lost fewer than 30 of his Tennessee boys.

I often wonder what the Indians of the trans-Appalachian West must have thought of this new tribe that had begun pushing into the western parts of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina and the eastern parts of Kentucky and Tennessee by the I760’s. The Shawnee, the Cherokee, and the others had never seen anything like it. There were no Lame Bears, Cornstalks, Running Deers, or Flying Crows, but there were Boones, Finleys, McClellands, Martins, McGees, Robertsons, McCoys, Buchanans, and Murphys aplenty. The new tribe was essentially an amalgam of several Anglicized Celtic peoples—Scots, Irish, and Scotch-Irish—with a good dose of English and some German thrown in. When the Indians slaughtered a few isolated farm families here and there, they thought that the bloody carnage would have the desired effect of intimidating the rest of the tribe into retreating east of the Appalachians. The Indians had no idea what they had done. They had aroused a fury that would not be spent in a day or two of raiding. They had ignited an infrared rage that would not be dissipated until their own tribes had been destroyed. They were shocked that the warriors of this new tribe followed them for weeks, for months, for hundreds of miles to wreak vengeance or rescue captives. This was not how the game was played. The Indian knew when to quit. The white man did not.

Perhaps if the Indians had understood the music of the new tribe, they might have realized that they were not just playing with fire—they were playing with a fire of white-heat intensity and power. The tribe’s jigs and reels were rousing, to be sure, but the melancholy airs said more about the people—dark, deep, poignantly beautiful melodies played on the strings of fiddles, carrying the people away to a distant land, long ago. The melodies tapped into the deepest recesses of the soul, recalling the thoughts, losses, passions, triumphs, defeats, desires, injustices, and dreams of generations of the tribe. Best not to provoke people who created such melodies.

Andrew Jackson was a member of this new tribe. His parents and two older brothers had immigrated to the American colonies in 1765 from Carrickfergus in the northeast corner of Ireland. He was born two years later in the Waxhaw frontier region on the border of North and South Carolina. His father died shortly before he was born. When the British army reached the western Carolinas in 1780, the 13-year-old Jackson joined other rebel frontiersmen in fighting the Redcoats. The next year, he was captured by the British. He rightly thought of himself as a prisoner of war and refused when ordered to shine the boots of a British officer. The officer responded by whacking Jackson across the face with a saber. Although suffering a deep gash which would leave a scar for life, the young lad was only strengthened in his resolve. His mother and two older brothers died as a result of British maltreatment.

Jackson went on to become a frontier lawyer, judge, politician, farmer, militia commander, and U.S. Army general before becoming President. Along the way, he performed feats of legendary proportions, among them his duel with Charles Dickinson. Dickinson was an extraordinary pistol shot, famous throughout Tennessee. Nonetheless, Jackson challenged him to a duel over remarks Dickinson had made about Mrs. Jackson. On the way to the field of honor, Dickinson warmed up by putting four rounds into a target from the prescribed dueling distance. The four bullet holes could be covered with a silver dollar. He then cut a string at the same distance with a single shot. The demonstration was meant to unnerve Jackson, but the iron-willed frontiersman had already decided upon an unusual strategy. He would not hurry his own shot and would allow Dickinson to fire first. Then, if still alive and in a condition to return fire, he would take slow and careful aim before shooting.

The duel proceeded with all customary formalities, and, with the men standing ten paces apart, the command to fire was given. Dickinson quickly leveled his pistol and fired. The bullet hit Jackson in the chest, narrowly missed his heart, and damaged one of his lungs. Somehow he remained standing perfectly straight, ignored the pain, and carefully trained his pistol on Dickinson. The pistol cracked, and a bullet tore into Dickinson, mortally wounding him. As Dickinson lay dying, Jackson strode from the field as if Dickinson’s shot had missed. He did not want to give the dying man the satisfaction of knowing that his round had found its mark. Although Dickinson would never know it, the bullet remained lodged next to Jackson’s heart and caused him pain for the rest of his life.

Jackson was the first President not to have come from the planting gentry of Virginia or the New England establishment. He was a Scotch-Irish frontiersman, and he became a symbol for Americans of the I9th century. He was self-made, roughhewn, decisive, independent, fierce, deadly, and courageous. He did not know how to take a step backward. He took risks. He made mistakes. He failed, and he triumphed. He fought Redcoats, redskins, and duels. Jackson embodied the spirit of his tribe and the spirit of the age.

Most 19th-century frontiersmen were versions of Andrew Jackson. They went by the names John Colter, Hugh Glass, Jed Smith, Tom Fitzpatrick, Joe Walker, Kit Carson, Ike Humphreys, Peter O’Riley, John Mackay, William Cody, Richard King, Lee McNelly, Granville Stuart, Charles Goodnight, Joe McCoy, James Butler Hickok, Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Marcus Daly, and thousands of others. Sometimes they went bad, or, at least, they became outlaws. They went by the names Jesse James, Cole Younger, William Bouncy, John Wesley Hardin, Clay Allison, Tom Horn, Bob Dalton, Bill Doolin, Tom McCarty, Butch Cassidy, and hundreds of others.

For good or ill, this was the tribe that swept across North America to the Pacific. These were the men who accompanied Lewis and Clark, who planted iron traps in the beaver streams of the Rockies, who stood shoulder-to-shoulder at the Alamo, who took the overland trail to Oregon and California, who worked the deposits of the Mother Lode, who grazed their cattle on the Great Plains. As the 19th century wore on, the tribe was joined by new arrivals from Europe—mainly from Ireland and Germany and, later, on the northern Plains, from Scandinavia—but the tribe’s essential nature had already been well established: Courage was admired above all else; death was preferable to dishonor; if challenged, a man was expected to stand and fight; a man’s word was his bond; great deference was paid to women; the innocent were protected; God had destined the tribe to inherit the continent.

These principles were absorbed by members of the tribe from childhood on, although boys and girls and men and women manifested them in different ways. Women most often expressed their courage in devotion to duty, enduring hardship without complaint, perseverance, sacrifice for their children, and the willingness to make yet another trek to a new frontier. The first woman to cross overland to California was Nancy Kelsey. She and her husband and her infant daughter were members of the Bidwell party, which set out for California in 1841 from Sapling Grove in eastern Kansas. The party had the good fortune to fall in with the great mountain man Tom Fitzpatrick and a group of missionaries that he was leading to Oregon. “Broken Hand,” as the Indians called Fitzpatrick, smoothed the way for the Bidwell party all the way to Soda Springs in southern Idaho. At that point, the trail to California separated from the trail to Oregon. Half of the Bidwell party decided to stay with Fitzpatrick and head for Oregon.

The remaining members of the Bidwell party were determined to strike for their original destination, California. Fitzpatrick drew them a map and off they went, 31 men, one woman, and an infant girl. They did not reach the Sierra Nevada until the end of October. Through the towering granite range they struggled, praying that a heavy snowfall would not leave them trapped. They climbed rocky passes, trudged over snowfields, descended into narrow canyons, and crossed and recrossed boulder-strewn streams. They ran out of food and supplies but not courage. Onward they staggered until the San Joaquin Valley came into view. They were the first party of American pioneer settlers to reach California. Nancy Kelsey was one of them. She had crossed the Sierra Nevada and she had done it barefoot and carrying her baby. Her shoes had long since disintegrated. She went on to have nine more children and live into the 20th century.

If Nancy Kelsey displayed courage and rawhide toughness in crossing the Sierra Nevada, so, too, did James Reed, Jr. He was five years old when he accomplished the feat. His family was part of the ill-fated Donner party, trapped in the Sierra during the winter of 1846-47. He was deemed strong enough to attempt to hike out of the mountains with a relief expedition that arrived in February. As he climbed upward in the deep snow from Truckee Lake toward the summit of the Sierra Nevada, he spoke of his father, who was already across the mountains organizing another relief expedition. It seemed impossible that the young lad, having eaten little or no food for several weeks, could continue, but he repeated to himself, “Each step brings me nigher Pa.” Several others died, but Jimmy Reed survived. Like Nancy Kelsey, he lived into the 20th century.

Six-year-old Johnny McGuire had absorbed the principles of the tribe. His family operated a way station at the southern end of the Owens Valley in California during the early 1860’s. While his father was away, a band of Paiute warriors attacked the station. Johnny and his mother, Mary, put up a furious fight but were forced into the open when the Paiutes succeeded in setting fire to the McGuire’s cabin. Two cowboys spotted the smoke rising from the cabin and galloped to the station. They found Mary McGuire riddled with 14 arrows and near death. Beside her lay Johnny, dead. He had been struck by six arrows, his arm broken, his teeth pounded out, and his head bashed in. Mary McGuire, wounded though she was, had somehow managed to pull every arrow out of her son. They had both gone down fighting—an ax was found alongside her body, and Johnny had a rock tightly clenched in his fist, indicating that, as a resident of the Owens Valley said in a newspaper report, the boy “died grit.” The Home Guard, a militia company of settlers, was in the field by the next day. The militiamen trailed the Paiutes for three days and then surprised them at a camp on the eastern shore of Owens Lake. Thirty-five of the Indians were killed, including two warriors shot by Johnny’s father.

The principles of the tribe changed little throughout the 19th century, although advancing technology caused some variations on the old themes. The formal duel of the first half of the 19th century was generally replaced by the gunfight following the introduction of the revolver. As a result, gunfights occurred with great frequency, especially in the mining camps of the Far West. No mining camp gunfighter was deadlier than John Daly. Born in New York City, he came to California as a teenager and began his gunfighting career in the camps of the Mother Lode during the 1850’s. In 1863, he was hired by the Pond mining company in Aurora, Nevada. The Pond was waging a legal battle with the Real Del Monte mining company over conflicting claims on Last Chance Hill. Legal expenses would run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Outside of court, the Pond and Real Del Monte would spend thousands more on hired guns. Daly and his “boys” were hired to oppose the hired guns of the Del Monte and to intimidate the rival mining company’s executives and witnesses.

Daly’s first gunfight in Aurora was with another hired gun, George Lloyd. A Saturday night found the two of them in P.J. McMahan’s Exchange saloon. A few words passed between them, and they went for their guns. A split second later both men were firing. Daly was unhit, but Lloyd slumped to the saloon’s floor, dead. Daly had, by most counts, killed his 11th man. The townsfolk of Aurora were unmoved by the death of Lloyd and by the deaths of other gunfighters. “So long as they did not molest peaceable citizens,” commented one of the town’s newspapers some months later, “their shooting and killing one another was borne with by the people with utter indifference.”

A month later, the Pond and Del Monte trial was moved to Carson City. There, John Daly ran into an old rival, Joe McGee, in the St. Nicholas saloon. McGee had killed several men in gunfights, including two of Daly’s friends. Now McGee and Daly went at it. Shots rang out, and McGee tumbled to the floor, dead. McGee was number 12 for Daly. The next month, the Pond and Del Monte trial ended in a hung jury, and the two mining companies settled out of court rather than go to trial again. The services of Daly and his boys were no longer needed, and they returned to Aurora. Daly reckoned that there was still one outstanding debt to settle before he moved on to other towns and new adventures. William Johnson, who ran a way station on the road between Aurora and Carson City, had been indirectly responsible for the death of one of Daly’s gang members. Daly decided Johnson should die. Coincidentally, none other than Johnson himself arrived at Aurora to sell a load of potatoes that he had grown at his way station. After making the sale, Johnson lingered in town to enjoy the night life. Daly, accompanied by three of his boys, intercepted Johnson and put a bullet in his brain. To make certain Johnson was dead, one of Daly’s boys cut Johnson’s throat.

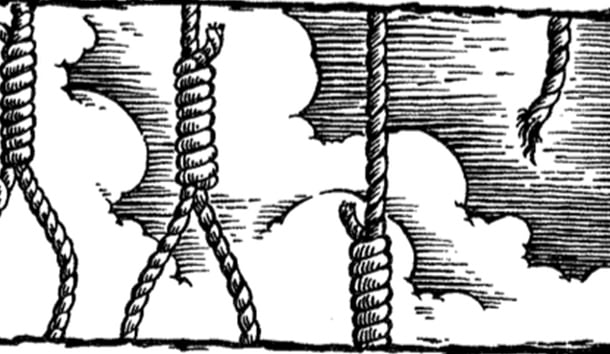

The next morning, Johnson’s body was discovered. The residents of Aurora were furious. Two men—be they professional gunmen, miners, teamsters, or cowboys—killing one another in something resembling a fair fight was one thing, and such occurred nearly 20 times during Aurora’s first few years, but Johnson’s killing was another. The Code of the West, the mores of the tribe, had been broken. Immediately, a vigilance committee was organized and an investigation launched. Arrests were made, witnesses interrogated, depositions taken, and evidence was gathered. All roads were guarded and patrols sent into the hinterland. The vigilantes operated with military discipline and precision. By the end of the week, John Daly and the three gang members who had been with him at the time of Johnson’s killing were in custody. At the same time, the official coroner’s jury rendered its verdict: John Daly, William Buckley, Jack McDowell, and James Masterson were responsible for the death of William Johnson. Official institutions of law enforcement and justice would be allowed to do no more, however. The vigilance committee announced that Daly and the others would now hang.

If Hollywood were to make this story into a movie, the four men would turn craven on the scaffold. Few in Hollywood today understand, let alone appreciate, the character of the men or the spirit of the times that produced the Old West. So what actually happened? Hundreds of vigilantes with fixed bayonets formed a hollow square around the scaffold while a crowd of 5,000 watched. Daly, Buckley, McDowell, and Masterson, according to the Aurora Times, mounted the platform “with a firm step, and surveyed the immense crowd with apparent cool indifference.” Daly pointed at a member of the vigilance committee who was brandishing a revolver and said, “You son of a bitch. If I had a six-shooter I would make you get.” He then took several silver dollars out of his pocket, threw them to the crowd, and declared:

There are two innocent men on this scaffold. You are going to hang two innocent men. Do you understand that? I am guilty. I killed Johnson. Buckley and I killed Johnson. . . . He was the means of killing my friend, and I lived to die for him. Had I lived I would have wiped out Johnson’s whole generation.

Buckley then made a similar speech, stating that he and Daly were guilty, and concluded by saying, “Adieu, boys. I wish you all well. All of you boys must come up to my wake in John Daly’s cabin tonight. Be sure of this. Good-bye. God bless you all.” McDowell, following Buckley, declared that he was innocent. Then, with a “Good-bye, boys,” he suddenly pulled a derringer from his pocket, put the gun to his heart, and pulled the trigger. It failed to fire. He hurled the gun to the ground with an oath, stepped back, and said, “I’ll die like a tiger.” Masterson then stepped forward, cool and possessed, and declared, “Gentlemen, I am innocent.” “Yes, Buckley and I did the deed,” added Daly. With that the four men had their hands tied and nooses adjusted around their necks. A minister said a final prayer, a small cannon was fired, and the trapdoor sprung.

Facing the hangman’s noose, these badmen were brave, cool, and unwilling to dishonor themselves. They were members of the tribe and understood that they had gone beyond the pale by killing Johnson. The only protest came over whether McDowell and Masterson should hang also. But even those two accepted their fate without a whine. Death was preferable to dishonor.

I cannot count the number of times I have heard professors, lawyers, radio talk-show hosts, and politicians try to temper the anger of the general citizenry at the outrages committed by inner-city gangs by comparing those gangs with the outlaws of the Old West. Beyond being young, armed, and male, is there anything at all that they have in common? Do Daly and his boys resemble the Grips? Gould the James boys, the Youngers, the Daltons, Bill Doolin’s gang, or the Wild Bunch be mistaken for the Bloods? In Aurora, men were fined and jailed for using foul language in the presence of women. There were no reported cases of rape and absolutely nothing to indicate that rape occurred but went unreported. There was almost no crime of any kind committed against women. Nellie Gashman, who spent 60 years on the frontier and roamed from Arizona to Alaska, was asked shortly before she died if she had ever feared for her virtue while trekking from one strike to another and living in nearly all-male mining camps. “Bless your soul, no!” she replied. “I never have had a word said to me out of the way. The boys would sure see to it that anyone who ever offered to insult me could never be able to repeat the offense.”

On the other hand, gang-bangers today impulsively rape. No matter what other crimes they commit—murder, robbery, burglary, carjacking—they also rape. When robbing, they target the young, the old, the weak, the innocent, and the female. Does this sound like the work of Jesse James, Cole Younger, Black Bart, Billy the Kid, Bob Dalton, or Butch Cassidy?

Kevin Rogers is a detective with the LAPD who specializes in investigation of gang-related homicides. He has been with the department for 24 years and is a Marine veteran who served as an FO in Vietnam. I asked him how he would describe the gang members he deals with. “Cowardly,” was his immediate reply. While I can cite hundreds of cases of frontiersmen— outlaw or not—facing each other and fighting to the death, Rogers could not recall a single instance of that occurring in Los Angeles. “The last time I saw anything at all like that,” said Rogers, “the gangs were the Sharks and Jets.”

Gang homicides in Los Angeles are almost always the result of the members of one gang catching a member of another gang off guard and alone. The lone gang member is simply executed. This does not remind me of the hundreds of characters I have studied in the Old West, men who stood firmly and resolutely in the face of deadly fire and coolly shot their adversary to death. “Get yourself heeled,” yelled S.B. Vance to Tom Carberry, who was unarmed at the moment. Both were former members of the Daly gang. Vance had arrived in Austin, Nevada’s latest boomtown, only to find Carberry there and to learn that Carberry was reigning as the town’s premier shootist. Not willing to suffer an inferior status, Vance issued the challenge. Carberry armed himself and met Vance on Austin’s main street. Vance drew his gun and opened fire. With bullets whistling by his head, Carberry coolly walked toward Vance and then, from a closer range, rested his revolver across his left arm, took careful aim, and killed Vance with a single bullet.

There really is no comparison between what occurred in the Old West and what happens in American cities today. No, if a comparison is to be made with the frontier, try looking at 20th century figures such as George Patton, Alvin York, Audie Murphy, Butch O’Hare, or Bull Halsey. Nor is there any comparison when it comes to presidents. Andrew Jackson would have chosen death before dishonor. He was the symbol of his age. And the symbol of our age—Bill Clinton?

Leave a Reply