Whimsy—clumsy or fantastic—fills the minds of those viewing the art of Marc Chagall. Two hundred oil paintings, gouaches, etchings, stained glass, and theater designs, chosen for their quality and their significance in the artist’s career, drawn from public and private collections throughout the world (including generous loans from the artist’s family), were on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from May 12 to July 21.

“The response to the exhibition has been extraordinary. So many people are coming to share in Chagall’s celebration of life and love, making the exhibition truly a tribute to him. We are only sorry that he did not live to see this wonderful outpouring of interest in the United States,” commented Anne d’Harnoncourt, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “It is unlikely that an exhibition such as this can be mounted again in our lifetime, so we are pleased that the museums and individuals around the world who have lent to the exhibition are permit ting us to keep their works of art two weeks longer.” The first Chagall retro spective to be mounted in the United States in nearly four decades, the exhi bition was organized by the British scholar Susan Compton, a specialist in Russian 20th-century art and theater design for the Royal Academy of Arts in London and for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philanthropic support came from the Pew Memorial Trust, the Boben Foundation, Pincus Broth ers Maxwell, Inc., CIGNA Founda tion, Knight Foundation, and the Fed eral Council of the Arts and Humanities. One hundred and thirty six thousand people had already visited the exhibition by mid-June.

Chagall died in March of this year at the age of 97 at his home in south ern France. He was the last member of that remarkable generation of artists who early in this century shaped our concept of modern art. France, and in particular, southern France, attracted some of the most creative minds of our age. A few of them, like Chagall, retained a residual yearning to return to their birthplace. During the twilight years, human beings turn their glances homeward. And the work of Chagall is best appreciated against the backdrop of his native Russia, where brutal treatment of Jews has long been the norm.

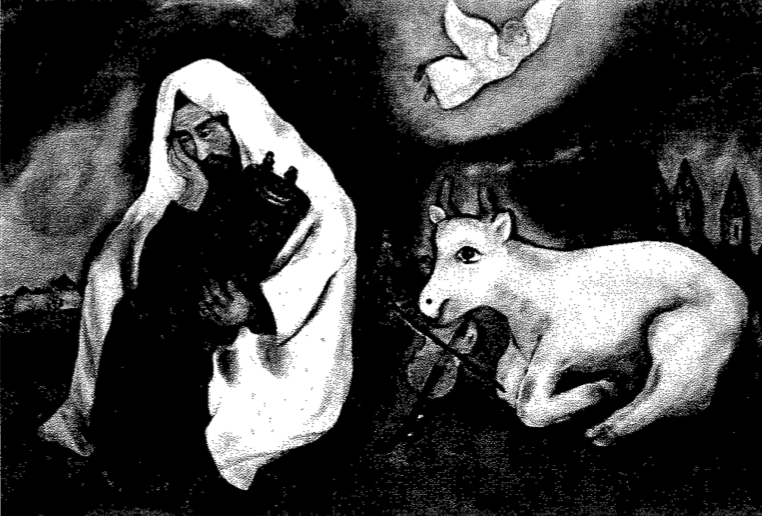

Born in Vitebsk, Russia, in 1887 of a Hassidic Jewish family, Chagall spent most of his life in France. But Jewish traditions and symbols, Russian icons and folk art, and memories of traditional village life filled his imagi nation and set him apart from the modern European artists he met in Paris. Anti-Semitic persecution in Russia has taken many forms, all of them vicious, but for Chagall the grief of being separated from his native country remained with him to the end. Visually, much of this sadness, intermingled with a riot of color, daz zling forms, topsy-turvy figures, is there for any viewer to see. Along with this profound sense of loss is Chagall’s child-like anticipation of a return.

Yet, in most of his works, Chagall brought a sense of conviction, a strong belief that no matter what ideology prevailed in his beloved Russia, none could rob him of his memories. In a sense, the Chagall imagery can be considered the reverse of the world conceived by Franz Kafka. Chagall’s metaphors—whether or not Andre Breton is correct in linking them with surrealism—do not haunt us like those conjured in “Metamorphosis,” The Trial, or “The Judgment.” That Chagall turned trauma and tragedy into a personal triumph is a feat wor thy of the noblest ideals of Western man.

While looking at the works of Cha gall, the viewer may be reminded of Longfellow’s The Slave’s Dream: “Again, in the mist and shadow of sleep/ He saw his Native Land.” Love is seldom an opiate, and whatever happens to any country, some of its sons remain proud and loyal to the end. Thus, Chagall celebrated his love for Russia and Russian Jewry through out his prolific life. Lyrical in feeling, Chagall’s work poetically blends layers of reality and illusion. “For the Cub ists,” Chagall once wrote, “a painting was a surface covered with forms in a certain order. For me a picture is a surface covered with representations of things (objects, animals, human be ings) in a certain order in which logic and illustration have no importance. The visual effect of the composition is what is paramount.”

The Philadelphia exhibition was wisely arranged to allow viewers to trace Chagall’s career from the early years at St. Petersburg to his final creations in southern France. The show began with a group of early works painted in Russia and included several of his celebrated paintings created in Paris before World War I. It is in these works that Chagall displays with bril liant color his synthesis of Russian imagery and Cubist structure. Also represented were the imaginative fan tasies in a broader style which Chagall invented in mid-life as he explored the techniques and themes that defined the saga of his career. The later works on display included the paintings and stained-glass maquettes devoted to the “Biblical Message” that preoccupied Chagall beginning in the 1950’s. The celebratory nature of Chagall’s best known work has often eclipsed the deeply moving reminders of war and suffering. The artist’s response to human tragedy is revealed in his de pictions of crucifixion, which Chagall sees as a symbol of great power for Christians and Jews alike.

Indicative of Chagall’s love for bal let and theater were a series of water color studies, choreographic sketches, and a curious mask for a dancing bear. These marvelous works find their roots, I believe, in St. Petersburg. After all, it was in St. Petersburg that Chagall had two teachers who were designers—one for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the other for experimental plays. And in the same great Russian city his fiancée, Bella Rosenfeld, stud ied acting.

Chagall’s later involvement in Rus sian and Jewish avant-garde circles led to commissions for such theaters as the Hermitage Studio in St. Petersburg, the Theater of Revolutionary Satire in Vitebsk (founded with Chagall’s assist ance in 1919), and the Jewish State Kamerny Theater (founded in Mos cow in 1920). Nontraditional in his approach to theater design as he was in his painting, Chagall incorporated folklore, Jewish symbols, farm ani mals, and upside-down figures in his backdrops and in the monumental canvases he painted for the foyer of the Jewish State Kamerny Theater. “Cha gall’s paintings,” Zubin Mehta (con ductor of the Israeli and the New York Philharmonic) said, “are beautiful. ‘The cow’s jumping over the moon.”‘

It was for the Ballet Theater of New York that Chagall did his first work in ballet, when in 1942 he designed the sets and costumes for Aleko. First pro duced in Mexico City, Aleko was set to music by Tchaikovsky on a story based on a poem by Pushkin, with choreog raphy by Leonide Massine, also a Rus sian expatriate. Delighted with his commission and inspired by Russian memories, Chagall unleashed new en ergies. In the backdrop for Scene 3, A Wheatfield on a Summer’s Afternoon, Chagall introduced two huge red suns blazing in a yellow sky above a wheatfield, from which emerge a scythe and a strange, fish-like creature. To the right, the hero Aleko rows a small boat. The ballet’s final tragic scene was played against the backdrop A Fantasy of St. Petersburg. Here Cha gall evokes the city, its hatue of the Bronze Horseman clearly silhouetted against the sky, an allusion to Push kin’s famous poem of that title. A white horse springs across the night sky, its nose touching the light from a candelabrum which has apparently strayed from a St. Petersburg ballroom of Pushkin’s era. In an interview at the time, Chagall explained his spare, dra matic approach: “I wanted to penetrate Aleko without illustrating it, without copying anything. I want the color to play and speak alone. There is no equivalence between the world in which we live and the world we enter in this way.”

“It is Chagall who emerges as the hero of the evening,” wrote the dance critic for the New York Times discuss ing the premiere of Aleko. “So exciting are [the backdrops] in their own right that more than once one wished all those people would quit getting in front of them.” Lovers of the ballet will be thrilled to note that among Chagall’s most famous stage sets still in use are those for Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird, created in 1945. His murals and decorations for theaters included the ceiling of the Paris Opera in 1963 and the two huge paintings for the foyer of the Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center in New York City in 1966.

Late in his life, Chagall embarked on a totally new creative endeavor stained glass. This new initiative ef fected a spiritual confluence of his incredible energies. The religious paintings and prints—both of which Chagall had executed throughout his brilliant career—came together in stained glass. Working in collaboration with Charles Marq, a French artist who specializes in stained glass, Cha gall brought a lifetime fascination with color relationships to this radiant, translucent medium. Chagall was 70 years old when he began to accept commissions in his new field. His stained-glass windows now illuminate religious and secular buildings around the world. His work in the private chapel of the Rockefellers at Pocantico Hills can be viewed year-round. In cluded in the Philadelphia retrospec tive were four sample sections for windows representing the 12 tribes of Israel commissioned by Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, for the synagogue attached to the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem.

From the early experiments in color to the mature achievement in stained glass, the Philadelphia exhibition ex plored the full range of Chagall’s long and fruitful career, reminding us in the process that through his jubilant fantasy, sly humor, and tragic drama, Chagall was true to himself, sincere in his feelings for Russia, and genuine in his concern for his people, the Jews. A lavishly illustrated catalogue, Marc Chagall, written by Dr. Susan Comp ton, is available for $12.95 (plus $2. 50 for postage and handling) from the Museum Shop, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Parkway at 26th Street, Phila delphia, PA 19101. Telephone: (215)763-100.

Leave a Reply