Not so long ago, nor all that far away, we knew our place. The old could command the young, parents command children, the well-born command the lowly-born, men command women, and the High King over all. No one need have any doubts about his duty. We all owed duties of deference to those above us, and of care to those below. Horses, dogs, and cattle had their position too (and one that was sometimes higher, in its way, than those of many humans). On the one hand, they could be punished for stepping out of line; on the other, they would be valued and rewarded for playing their part. Wild creatures were assigned to similar roles, at once a reflection of, and a justification for, the status society of civilized humanity. The vision still has enormous influence, even among people who think they have escaped. Witness that reactionary fiction The Lion King, which requires us to believe that the land will be fertile, and “at peace,” if the rightful king (high up in the food chain) withstands the incursion of undisciplined hordes (hyenas) who seek to transcend their natures.

Status society does have merits. In its proper form, it is because we fulfill our duties of care, to our inferiors, that we may be owed obedience. As Humphrey Primatt, an 18th-century Anglican clergyman, insisted in his plea for decent treatment of nonhuman animals, The Duty of Humanity to Inferior Creatures (1776), “He who boasts of the dignity of his nature and the advantages of his station, and thence infers his right of oppression of his inferiors exhibits his folly as well as his malice.” Those duties of care, and forbearance, were diminished when political and moral theorists successfully challenged status society in the name of contract. Instead of owing obedience to our natural superiors, the story went, we owed it only where there was, or could reasonably be thought to be, a contract of obedience. Mutual obligations, it was said, rested on an actual or hypothetical agreement, and a decent human society, accordingly, imposed identical duties of care and forbearance on all human beings. Nonhuman creatures, being incapable of making contracts or abiding by them, were excluded, as they had been by the Stoics, from all forms of justice. On the one hand, they could not be punished (strictly speaking); on the other, nothing that was done to them could be unlawful. They existed, as the Stoics had said, entirely for our use and profit. Nonhuman creatures had a lower status than any human being. Even as status crumbled as a moral and political norm for civilized humanity, it was reinforced, in its least respectful form, for everything nonhuman. Actually, uncivilized humanity, or “savages,” were also treated as fair game: they too could not be judged to “own” the land they lived on, or to have made bargains that a civilized court would enforce. Nowadays, we pay lip-service to the thought that all human beings have equivalent rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Nonhuman creatures are still largely undefended.

In its 17th-century beginnings, contract society did not in fact give absolute rights of ownership and use to human beings. Strictly, we could never own the land itself, but only, at most, its fruits—and those on condition that we left as good for others. The moral doctrine that recent environmentalists have attributed (no doubt correctly) to the native peoples whom European colonists despised and conquered was actually one that those same Europeans held. The Minister of the British Crown who recently quoted Ruskin in support of the Rio summit on environmentalism might as easily have quoted Jefferson, Locke, or Leviticus. We had no “right” to destroy the land, nor deny it to other creatures who had as great a need of it as we. Nor could we have any “right” to treat nonhuman creatures cruelly. “You bought [the horse] with your money, it is true, and he is your property; but, whether you are apprised of it or not, you bought him with a condition necessarily annexed to the bargain. You could not purchase the right to use him with cruelty and injustice. Of whom could von purchase such a right? Who could make such a conveyance?” Ownership, in English and other law, has never conveyed a legal right to do exactly as we please with what we own, and there were plenty of rulings in our history to dictate some decent treatment for creatures that were our “property” (as being things that we could buy and sell). “The righteous man has a care for his beast, but the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel,” so the Book of Proverbs dictated. Even when the wicked did nothing “against the law” in beating their dogs, their horses (or their wives and children—since it took a long time to remember that such things were also human), what they did would meet with public disapproval.

For though the surface doctrine was the Stoic one, that nonhuman creatures could not be treated “unjustly,” the tradition was clear that certainly they could. “You shall not muzzle the ox that treads out the corn” (Deuteronomy 25:4); “you shall not yoke ox and ass together” (Deuteronomy 22:10). Both these commands mean more than what they simply say: the clear implication is that the animals who work and suffer for us shall not be refused their pay, nor put to work in ways that do not suit their natures. Everyone understood that there was, after all, a sort of bargain with domestic creatures—as almost everyone in Britain now condemns the present treatment of (male) calves surplus to the requirements of the dairy industry. The bargain was not an explicit, verbal one, but neither was the hypothetical bargain that we human citizens were said to have struck. There are very few cases of any explicit bargain at the root of any human state (Locke can identify only such occasions as those bargains between desperate ruffians, aA/a the founders of Rome, that enabled them to seize a territory and make a state). The point about contract talk is simply to direct our attention to the advantages we individually gain from keeping the present peace. The peace is one that should be kept (it is a real peace), if all of us can gain from it. Similarly with our domestic creatures: our bargain is that we look after them. The word of the Lord to Ezekiel:

Prophesy, man, against the shepherds of Israel; prophesy and say to them, YDU shepherds, these are the words of the Lord God: How I hate the shepherds of Israel who care only for themselves! Should not the shepherd care for the sheep? You consume the milk, wear the wool, and slaughter the fat beasts, but you don’t feed the sheep. You have not encouraged the weary, tended the sick, bandaged the hurt, recovered the straggler, or searched for the lost; and even the strong you have driven with ruthless severity. . . . I will dismiss those shepherds: they shall care only for themselves no longer; I will rescue my sheep from their jaws, and they shall feed on them no longer (Ezekiel 34:1-10).

I acknowledge, of course, that the words refer to the rulers of Israel: but the metaphor makes no sense, in its context, unless real shepherds were really meant to care for sheep.

There were also rules for our relation with the wild. You shall not take both mother and young from any nest (Deuteronomy 22:6, Leviticus 22:28), nor plough up all the fields so as to deny food to the poor, the stranger, or the wild things in your country (Leviticus 19:9, 23:22, 25:6). If we do, the story went, we would be thrown out of the land: we enjoy it only on condition that we do not take it wholly for ourselves. “The whole world has rest and is at peace; it breaks into cries of joy. The pines themselves and the cedars of Lebanon exult over you: since you have been laid low, they say no man comes up to fell us” (Isaiah 14:7-8). The land shall have the sabbaths we denied to it (Leviticus 26:34).

I mention these commands, these tacit bargains, not to exalt one moral and religious tradition over all. Similar injunctions can be found elsewhere, and it is important that those who campaign for international change should find the appropriate seeds for ecological and humanitarian change within the customs of the relevant country. My purpose is at once to answer the common claim that Christian or Jewish tradition is “environmentally unfriendly,” and to lay out the processes that have led us, in the settled West, from one moral code to another. The contract society eliminated, or strove to eliminate, many failings of status society. It did not wholly eliminate its merits, but the nonhuman suffered more as a result than need have happened. The older tradition included many duties of care and forbearance to the nonhuman, duties that could be rationalized as products of a sort of bargain quite as easily as liberal, human rights.

The next great shift in moral sensibility, which has also proved to be double-edged, introduced the notion that pain was, as such, an evil. We ought not to cause such evil, and maybe ought to take steps to prevent it. Until the 18th century, moralists probably took it as their task to show that pain was not an evil, or not one that decent people minded much about. It was wrong to betray one’s friends and country, wrong to steal or to murder; greed, ill temper, and unchastity were wrong. Possibly it was wrong to rejoice in the undeserved suffering of others; it might also be wrong to regret their deserved suffering. Those moralists who then began to insist that pain was after all an evil, something that should not exist, and perhaps that it was the only real evil, were vulnerable to the charge that they were taking on the mind of brutes. Brutes, after all, felt pain: if pain were an evil, or the main or real evil, then we ought (absurdity!) to take their pain into account in reckoning on right actions. If brutes’ pains mattered to these moralists, it must be because they were themselves brutish, cowardly, and licentious. The moral school that came to be called “utilitarians” played an important part in pressing for legislation to regulate the treatment of both domesticated and wild animals. If they could suffer, then we ought to treat them gently, and protect them against what injuries we could. It is unfortunate that “utilitarian” arguments are now taken to be those that turn on quantifiable, human advantage: save the whales because they might be useful later! The founders of the school would have been appalled by this: stop harassing the whales because it gives them serious pain, and has not even the excuse of sparing others pain.

The older ethical system urged us to live as decent human beings, and might easily have made the wider demand explicit: to allow or to help nonhuman creatures to live as decent a life according to their kind. The righteous man would have a care for his beasts, but would expect to see them suffer for good causes, ones that promoted virtuous living. The newer system denied that anything should ever be made to suffer, except to reduce the sum total of suffering. That dangerous concession made it right, after all, to make animals suffer if human suffering could therein be reduced. And moralists retained enough of the outlook of a status society to believe, without thinking much about it, that our suffering was of another order than theirs. Animal pains and pleasures must be merely physical. Humans would suffer agonies (it was implied) if they could not have their favorite foods, or watch their favorite sports, or find out fascinating truths about the world. Humans suffer (it was asserted) far more pain at bruises, wounds, infections, cancers. So though we might regret giving pain to “animals,” it must be better than allowing “humans” to have those pains instead.

It follows, unfortunately for nonhumans, that the humane, welfarist impulse had much less impact than its founders would have wished. Some things were outlawed: all those things, in fact, that our chief legislators did not themselves much want to do. Bull-baiting, cockfights, dogfights, torturing cats for fun became illegal—though not without protest from those who thought that these practices encouraged moral virtues such as courage (or at least indifference to blood and pain) and love of glory. But of course, it was urged, we should not Go Too Far: nonhumans, after all, are of another kind than humans. They remain, in fact, within a lower status, and depend upon our fluctuating kindness rather than on clear bargains or radical utilitarian concern.

Kindness does fluctuate, and so does our perception of what counts as pain. Mere (stabbing, throbbing, aching) pains of a clearly “physical” kind are not the only ones we now acknowledge. Animals may suffer agonies of boredom, loneliness, frustration, stress, which are far worse than momentary pains. Animal welfarists may acknowledge these and seek to prevent or cure them. They may even begin to wonder whether it is wrong to deprive a creature of a happy life, or of some natural functions, even if it does not actually suffer: a creature blinded from birth has been deprived of something good, even if it never knows its loss. Once that step of sympathy is taken it may even occur to us that killing a happy (or potentially happy) creature is a wrong. This goes beyond the muddled doctrines that we have inherited. Conventional moralists will usually agree that hurting animals (without a good excuse) is wrong, but not that it is wrong to kill them (painlessly). As so often, even conventional moralists are not quite so sure in practice: a family that brings a pet dog to be killed merely because they’re tired of it, or want to go on holiday, are surely displaying some defect of character, betraying some implicit bargain. We no longer allow our children to go out killing cats, squirrels, or birds merely to try out their catapults or guns. We have begun, in fact, to think that causing pain and death, except for very good reasons, must be wrong. Whether culinary or cosmetic reasons are sufficient is in doubt. Are even “medical” reasons good enough? Erazim Kohak asks in The Embers and the Stars (1984), “What justifies the totally disproportionate cost of our presence? Ask it for once without presupposing the answer of the egotism of our species, as God might ask it about His creatures: why should a dog or a guinea pig die an agonizing death in a laboratory experiment so that some human need not suffer just such a fate?”

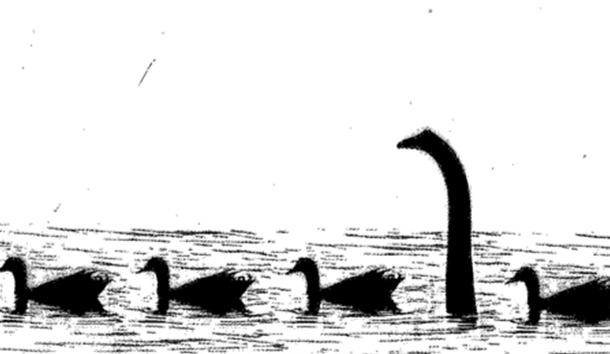

Part of the reason for this gradual shift in moral sensibility is the discovery that our predecessors were mistaken about facts. For centuries we had believed that human and nonhuman creatures were of radically different kinds, and we were in a special sense God’s favorites. The status society itself was partly based upon a wish to treat the different classes, sects, and sexes of humanity as if they were different species. Our view of nonhuman nature (as I said before) was formed in a complex interaction with our view of human nature. Because we had to assume that classes, sects, and sexes were distinct, we projected just those patterns on the natural, nonhuman world (as in The Lion King). Because humans and nonhumans were of different kinds, it need not be surprising that we should use quite different rules about them. But in the last century, we have learned that the older account of “species” was mistaken. Creatures are not “members of the same species” because they share a distinct nature, unlike any other. They share as much as they do with each other (and many things with others) because they are members of a group of interbreeding populations whose boundaries in space and time are vague. We have plenty of evidence that other, nonhuman animals are very much like us: they do not only “feel pain,” but engage in social intercourse, make plans, make choices, very much as we do. The other great apes, in particular, live lives entirely recognizable as hominid, to the extent that a truly objective taxonomy might reckon chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans belonged to the same genus, Homo. I hope to live to see an international recognition of their “human rights,” and legislation to protect them from abuse. Whether the same rights can ever be extended to all creatures must be doubtful; if we cannot even extend them to the apes, we must begin to doubt that any of us can have them.

As we begin to realize that our status is suspect, that we cannot just go on accepting the pretexts and compromises that allow us, in practice, to do almost everything “we” choose to do, to “animals,” to “savages,” and to the land itself, we need to work out bargains, and new wavs to enforce them. We need a “new pact with nature.” One route to this involves a Global Ecological Authority, “with teeth.” Unfortunately, a GEA would inevitably be a global government, an absolute dictatorship, and most of us would shrink from such a thing. Even if it were founded with the best of intentions, it would most probably be run with the very worst. The alternative route to moral (and environmental) sense is the slow and careful formulation of national law and international treaty, founded in the (differing) moral sensibilities of peoples around the world. We do need some general principle, and I would propose the liberal principle itself, suitably modified to include, explicitly, more of the world’s creatures than past liberals thought to do. We should act according to those laws that allow as many creatures as possible, of as many kinds as possible, the chance of as decent a life as possible. This is not to say (but rather to deny) that we should always act to prevent, cure, punish injuries. In a liberal world creatures do suffer and fail and die. The liberal bargain simply insists that our mutual dealings should not be rigged to promote the interests of any particular individual or group. We should not muzzle the ox, nor plough up every field, nor seek to control the lives of creatures who can manage quite well by themselves.

That vision is not of the Peaceable Kingdom when “none shall hurt or destroy in all God’s holy mountain,” but only of the liberal society, where we are at liberty to try our luck, and to make, and enforce, such bargains as can be seen as fair. In moving toward its realization we should aim to incorporate insights and working practices from earlier moralists. Status society, contract society, virtue ethics, and utilitarian ethics all contribute something to our understanding. Legislation and international treaty take shape over many years, according to no one principle. What matters most is the direction that we are heading. And we will of course see no improvement as long as the demand exists for something that we cannot achieve without injustice. Even decent people choose to ignore the costs of their favorite foodstuff, favorite game or pastime or ideal way of life. Once they begin to understand those costs, they may eventually make fewer demands. Until they do, all legislation to protect the land, and the creatures that we share it with, will be mere words. The change, if there is to be a change, will start with individual decisions, individual surrenders.

Leave a Reply